Covid 19 Edition

Africa: The Casualty of Lockdown

So far, Africa has been the continent least touched by Covid-19. Virally, at least. But the economic, social and political challenges that the continent is facing are likely to have a significant impact on the West’s own recovery strategies as the world comes out of hiding — and they are likely to affect its relationship with the continent long-term.

For the moment, a steady refrain can be heard from the poorest Africans as they face the dual hardship of lockdown and unemployment.

“It’s hard to get a job due to the measures put in place,” Joseph, a casual labourer from the Mathare slum in Kenya,” said. “Now I am staying at home with no income and I have a family to take care of.”

As of the end of April, Africa faced just more than 33,000 confirmed cases, the majority found at the continent’s poles, South Africa, Morocco, Algeria, and Egypt, with a relatively small number of roughly 1,500 confirmed deaths.

Of course, having such a low capacity to test, these numbers are likely to be under-reported and may yet balloon. With the weakest health systems in the world (50 critical care beds for the average low-income country in Sub-Saharan Africa, versus 7,000 in the UK), the health impact could be very significant.

However, the non-health repercussion is already being felt: the 24 million African jobs that rely on tourism have largely disappeared; tax revenue in Nigeria – two-thirds of which comes from oil – has dried up; dependence on China, Africa’s largest trading partner, and other global supply chains has resulted in price increases for basic local commodities, including a 7.5% increase in the price of imported rice in Abuja and Lagos.

In early April, the World Bank predicted that the continent would face its first recession in 25 years because of the Covid-19 pandemic. Fears lurk about growing social tensions and unrest. Africa is dealing with a myriad of micro conflicts, and witnessed riots as a result of social restrictions during Ebola breakouts in Central and West Africa. Those already seen during the Covid-19 pandemic may only escalate.

The dilemma that the continent’s leaders face is whether the response to the crisis may cause more problems than the virus itself. All but one of the 54 countries have implemented some form of lockdown, and this has caused a series of concerns in the following three areas:

Economic:

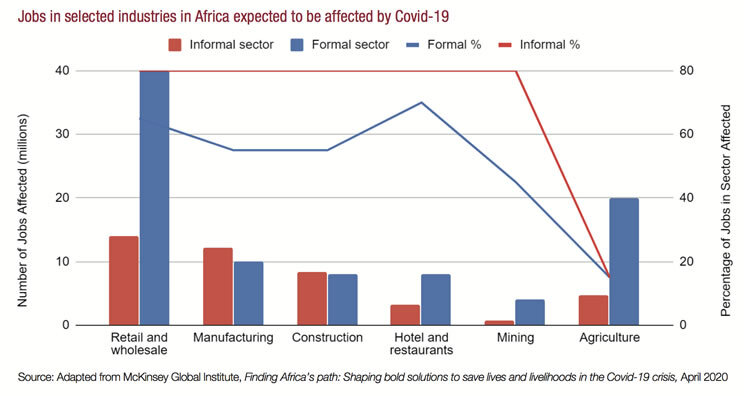

Some 150 million African jobs are estimated to be vulnerable to the crisis. Some face unemployment due to broader global and macroeconomic issues, but the majority are affected by the lockdowns. More than 80% of jobs in Sub-Saharan Africa exist in the informal sector of irregular trade and services. Motorbike taxis have been banned in Uganda, small trader markets have been closed across the continent, and many of these informal ‘hustles’ have been forbidden. While the global North has rolled out a wealth of safety nets, most countries in Africa have introduced lockdowns without any form of income replacement. The fact that 439 million people on the continent already live in extreme poverty (under $1.90 per day), means that even a short-term reduction in salary can have drastic impacts on their capacity for basic survival.

A recent survey by the Population Council’s of informal settlements in Nairobi found that four out of five people have had a total or partial loss of income as a result of the lockdown and 64% of men and 71% of women have skipped meals in the past two weeks as a result.

Source: Source: Adapted from McKinsey Giobal Institute, Finding Africa’s path – Shaping bold solutions to save lives and liveihoods in the Covid-19 2020

Medical:

While the potential strains of Covid-19 on African health systems are clear, the very weakness of these systems means that the distraction of the virus will result in huge gaps in basic healthcare provision, from delays in regular immunisation to routine emergency care. Studies suggest that a lack of healthcare provision for non-Ebola issues during the crisis in West Africa resulted in increases in maternal mortality of 38%-111% across Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, and an additional 11,000 deaths across the three countries from malaria, HIV and tuberculosis. Moreover, the incapacity to earn income from informal sectors suggests that it is likely more will die from their inability to acquire basic medication than will die from Covid-19 itself.

Political:

“Dictators love lockdowns” argues Togolese human rights advocate Farida Nabourema. Many African leaders have deployed state of emergency legislation to introduce sweeping powers that benefit their own interests. In Nabourema’s Togo, aid has been directed through politically sensitive systems that require citizens to submit their voter IDs. In Malawi, bans on public gatherings have helped the government restrict opposition groups in already turbulent times. In South Africa, certain xenophobic political interests used the early period of the crisis to ban non-South-African-owned spaza convenience shops and to build a 40km fence with neighbouring Zimbabwe (despite it only facing 11 cases at the time to South Africa’s 1,845). Many of Africa’s citizens will argue that the continent does not need lockdowns. It is the youngest continent in the world, with a median age of 19. In Japan, fully 28% of the population falls into the most at-risk cohort of over 65s, but Africa has less than 2% in that age group. In Uganda, 48% of the population is under 14. Can African leaders justify the economic and social impacts on their populations of their Covid-19 responses? One thing is certain: the continent will struggle to keep its young population under lockdown for long. If the proverbial cure is worse than the disease, then metaphorically Africa must surely by Covid-19’s patient zero, a continent that is most likely to have the earliest and most severe case of that old adage.

And the outcome of Africa’s dilemma will go far beyond its borders as the world starts to open up. Europe and North America may proudly stamp their ‘eradication’ seal on the Covid-19 virus at some point in the next year, but the virus is likely to continue slow-burning within populations with weaker health systems for much longer. Potentially, this will leave multiple re-entry points back into populations of the global North. As UN Secretary General, Antonio Guterres, said: “The Earth’s catastrophe makes clear that we are only as strong as the weakest health system.” How will the North respond, and how will this dynamic play out?

It could either lead to a sort of isolationism — longer-term travel restrictions on some countries in Africa — or, perhaps, to embracing the need for collaboration. Ongoing lockdowns on the continent will be difficult to maintain without either a global-North-backed furloughing of a continent, or seriously detrimental political and social trade-offs. We shall soon see if the continent is interested in any serious dialogue. The perception of the West having a monopoly on expertise and leadership in such health emergencies has been sorely tested by its failed response to the crisis, both domestically and globally.

Guterres is clearly seeking a unified response. “Global solidarity is not only a moral imperative, it is in everyone’s interest,” he went on to say.

But clarion calls are already being heard for the pandemic to be used as a catalyst for the de-colonisation of Africa, removing its dependency on external actors — so we must see if everyone in fact agrees.

Christopher Maclay has worked on economic development and employment programmes across Africa and South Asia for the last ten years. Most recently, he led operations for a tech start-up connecting informal sector labourers to jobs in Nairobi.