Winter 2019

Ahead of the Next Crash – Or Have We Learnt Our Lesson?

A spectre is haunting the world’s financial markets. It is the fear that no matter how well things are going now, a new financial crisis will come. And when it does the authorities will have no ammunition to deal with it — because it has all been used up.

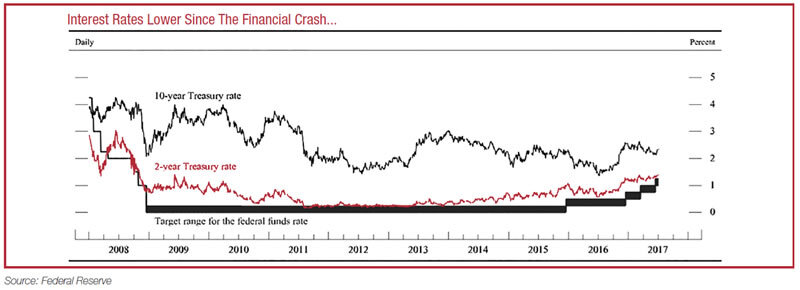

The official response to the Great Financial Crisis was slow getting started but when it came, it was massive. Interest rates were slashed, governments took on themselves the huge debts which financial institutions were unable to pay. The attitude was best summed up by Mario Draghi, who promised to do “whatever it takes” to save the Euro and then delivered in the face of strong opposition.

But with interest rates still close to zero and government debt way above the levels that respectable opinion thought bearable before the crisis, the question is what is left in the armoury.

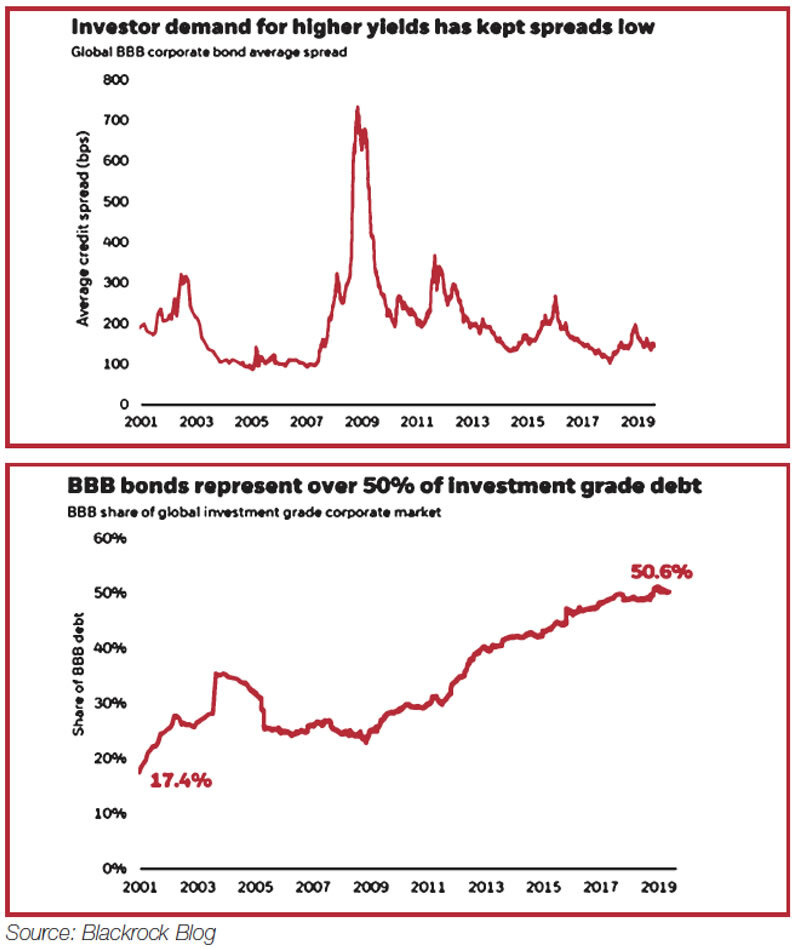

Some of the measures taken to save the system are now putting strains on it. The yield on government bonds in some countries is now negative. This is squeezing the banks, who are increasingly vocal in their complaints. Institutions which rely on income from bonds, like pension funds, are being forced to buy bonds of a lower quality just to get higher interest rates.

Access to virtually free money is leading to some bizarre features. Technology start-ups have been allowed to run huge losses without any real sign of profit to come. So much money is available that some take cash they don’t need because of threats the money will go to launch a competitor.

While they remain private these firms get huge valuations — until exposure to the public market place leads to a nasty crash.

But that hasn’t stopped stock markets from rising to record levels. In the past 10 years the S&P 500, the most widely quoted US index, has risen from 1109 to over 3000 — an average of over 11% a year. Equity markets in other parts of the world have shown similar rises. Add in dividends and those shareholders who bought when the Great Financial Crisis was at its worst have done very well for themselves.

Source: Federal Reserve

Simple logic tells us that this can’t go on forever. Share prices are going up much faster than the economy which supports them. Profits rising faster than wages have helped sustain the stock market boom, but there are some signs that such profits will be harder to make in future years.

What lies behind this performance? Partly, no doubt, it is simply because the panic selling of the Great Financial Crisis just made shares too cheap. But mostly it comes from the extraordinary measures which have been adopted by central banks.

Not only have they cut short term rates to unprecedented levels, but they have driven down the long term interest rates through a bond buying binge never seen before, usually referred to as Quantitative Easing.

Promises to keep interest rates low for a long time had little effect; markets know promises can’t be trusted. “Show me the money” is the only thing markets believe. And money has been shown in incredible quantities. And this has meant that money can be borrowed, by those who have the right connections, almost as cheaply for ten years as for two.

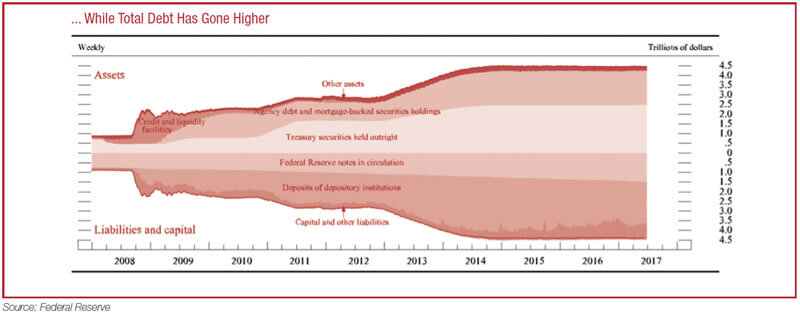

The Fed bought about $3 trillion of bonds, just printing the money to pay for them. In fact it did not even need to print it, but instead simply told the banks it bought it from that the money had been added to their accounts.

Initially there was much fear that all this money could lead to high inflation. Much effort was spent persuading the markets that, as soon as recovery came, the money would be sucked back. This probably just made recovery more hesitant, because whatever problems the world economy has had over the past 10 years, high inflation is not one of them.

But the growth of the real economy has been disappointingly slow. And this shows the limits to what easy money can do. In a world of weak demand, the problem is finding useful things to do with the cheap money on offer. This problem of the weakness of cheap money was described by the long-time head of the Fed, Marriner Eccles, as “pushing on a string.” (The hawkish fear that one day all this money will hit us with a surge of inflation that might be called “pulling on a spring.”)

Just how dependent the financial markets are on ultra-low rates fuelled by Fed buying can be seen from quivers on the repo market in the past few months. This is the place where banks trade short-term funds with each other, and interest rates there suddenly shot up a couple of months ago. The Fed was forced to start buying $60 billion of bonds a month to smooth things out, reversing its earlier policy of trying to wind down its bond holdings.

That, and three cuts in interest rates, have been enough to keep markets going up. But they haven’t answered the question of whether this is the best way, or even an effective way, of keeping the economy going.

Persistent slow growth in the west has led former US Treasury Secretary to revive the term “secular stagnation,” first used to describe the long slump of the 1930’s.

Some of the problems may just be on the supply side. Fewer babies eventually means fewer workers. Changing technology can sometimes slow growth. For example, the prospect of electric cars may be discouraging investment in conventional car plants more than the new technique is ready for investment and productivity, for all the talk of robots taking jobs, has been growing very slowly by past standards.

So, slow growth may just be because economies in the west are less dynamic than they were, and less dynamic than that in fast-growing countries like China.

But there is also a worry about demand. Unemployment is low but wages have risen little. Consumption, which always accounts for most demand, is held back by this.

Low interest rates encourage people to buy on credit — but we have seen that movie before. Eventually there comes a time when the lenders realise that the borrowers will never be able to pay the money back, as happened in the mortgage crisis which played an important role in the crash a decade ago.

What conventional analysis said was that as the economy recovered and full employment returned, wages would start to rise. This would increase consumption, push up inflation, the central banks would raise interest rates and we would return to a world like the previous normality. In that normality, interest rates would be higher than they are now and in any downturn they could be cut.

It hasn’t happened. We seem stuck in a deflationary world. Some of the reasons are obvious, such as the emergence of low cost countries and the weakening of unions. Some still have not been identified. But in any case, if something goes wrong rate cuts aren’t really an option.

More QE is and indeed the latest round of bond buying by the Fed looks suspiciously like it. But attention is increasingly being paid to a more direct way to get money into the parts of the economy where it will do good. QE is a curiously convoluted scheme. The government pays for activities by selling bonds to commercial banks. The Central Bank then comes along and buys the bonds which now belong to the central bank which belongs to the government. Everyone makes money.

But the net effect is the same as if the central bank had just printed the cash and handed it to the government. So why not cut out the middlemen and have central banks fund governments direct?

That is the controversial argument known as Modern Monetary Theory. It goes against everything which became conventional wisdom when inflation was high and hard to reduce. The Treaty setting up the Euro has a specific ban on central banks funding governments or buying new government bonds. But the measures the ECB adopted to handle the European crisis have much the same effect.

It seems likely that, unless inflation surges, this kind of central bank action will be the norm in future, not the exception. And that leads on to the other leg of policy which may have to be more important, fiscal policy.

Economics since the 1930’s has seen a series of revolutions and counter-revolutions. Keynes provided the intellectual backing for the idea that government deficits, properly used, could be a more effective way of managing the economy than monetary policy alone.

In the 1970’s that idea was rejected. Whereas central banks can cut or raise rates at a moment’s notice, changing taxes needs laborious legislation. By the time the tax change works through, the economic situation it was designed to address may have changed.

A general distaste for politics and politicians, always thought to be on the lookout for electoral favour from giveaways, was thought to mean that fiscal policy had a bias to inflation. By saying that short term economic management should be done entirely by central banks an anti-inflation bias is built into the system.

But with inflation dead and interest rates about as low as they can go, an activist fiscal policy looks likely to be an essential tool in fighting any future downturn. Even in Germany, long the most opposed to using fiscal policy to get expansion, there is talk of a wave of government spending and tax cuts if the economy goes south.

How this can be done in practice is still unclear. Some want expert panels to decide whether fiscal policy should be loose or tight in any given year. Others would like to give greater power to governments or to supranational bodies, as in the idea for a European fiscal policy.

The best thing would be to decide the framework for this now. But economic policy never works like that. It is only when the crisis is upon us that people concentrate their minds.

So how likely are we to get a crisis and will the policy makers be able to respond?

On present trends we are not likely to see a repeat of the 2007–9 period, when all the world’s banks only survived through government bailout. This is because the risks are not concentrated in the banks in the way they were then. For example, just before it went under, Lehman Brothers claimed it had a net worth of $30bn because it owned assets worth $630bn and had debts of only $600bn. All that needed to happen was for its assets to go down 5% and it went bust.

The big banks hold smaller portfolios now. For example, Goldman Sachs, which did better than most in the crisis, now only takes one quarter of the risk it did then.

But that doesn’t mean that total risk is down. It is just held in different places. The pension funds and insurance companies, desperate to get yield to pay their policyholders, have been buying more and more bonds which are only just above junk grade. If the economy goes wrong, many of those bonds will default and the pension funds will find they have huge deficits.

The difference is that these deficits can exist for a long time without bringing the system crashing down. That provides a huge cushion against a crisis getting out of hand. To some extent it is what happened after the dot.com bubble, when share prices and bonds collapsed without setting off a crisis because the losses were hidden away for long enough for them to be recovered.

So, fears that in a new crisis the authorities won’t be able to handle it are overblown. But they are, paradoxically, very healthy fears. Markets are always a battle between fear and greed. Nothing did more to make the Great Financial Crisis inevitable than a belief it could never happen. Because that is what lay behind the truly crazy risk taking which lead up to it. The day you are told that the stock market will never go down is the day to sell.

David Blake is a financial analyst and commentator.