Covid 19 Edition

Building Bridges Out of the Crisis: But Where Will They Lead?

Making predictions about the course of Covid-19 itself is hazardous. The virus itself is new. No one can be sure how it might subsequently mutate. We don’t know whether Covid-19 will exhibit a seasonal pattern. An effective vaccine is currently a product of our imaginations, not reality (even if reported progress appears to be reassuringly rapid). We may be only in the foothills of discovering an effective antiviral drug. And, thanks to a shortage of testing – both for current sufferers and for the “recovered” who may have antibodies – we don’t know what the true mortality rate is.

Lockdown and herd immunity

We do know, however, how the majority of governments have reacted to Covid-19: the original lockdown in China’s Hubei province is increasingly being emulated — to varying degree — elsewhere.

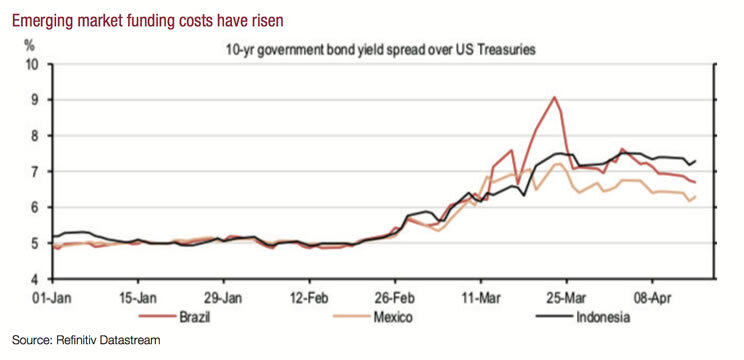

In truth, there are two versions of lockdown. The first takes places within nations. Its success varies depending on the quality of the housing stock – the more slums, the more difficult it is for the public to comply with social distancing guidance – and the availability of financial resources to allow businesses to go into hibernation and workers to be furloughed. Emerging markets often score poorly on both counts, one reason why financial outflows from emerging economies in the early months of 2020 were so enormous.

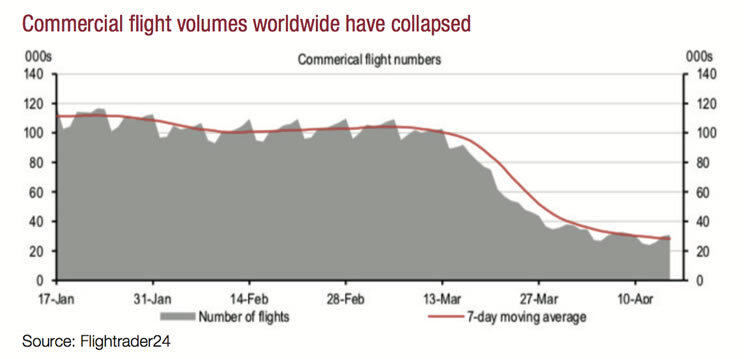

The second version of lockdown – the one that has been so damaging for airlines – takes place between nations. China’s internal lockdown – primarily affecting Hubei Province and, within it, Wuhan – may have come to an end in mid-April but its external lockdown remains. Other countries in the process of easing severe lockdown measures will doubtless take a similar view. One result is likely to be a persistently lower flow of people between nations (particularly between developed and emerging nations) with potentially huge implications for travel and tourism, together with migrant labour flows and their associated remittances (a story with notable resonance for migrant workers from the Indian subcontinent and the Philippines).

Source: Flightrader24

These differing experiences, in turn, suggest that the global economy will be unable to fire on all cylinders for many months, if not years. The connections upon which globalisation depends – most obviously, the increasing freedom of movement of goods, services, people and capital across borders – will be stymied, necessarily restricting the rate of global growth. And, in the absence of a vaccine, all countries will be vulnerable to reinfection, suggesting that intermittent lockdowns – notably between countries — may be a fact of life for a considerable period of time.

Inner reflections

In the absence of globally- or regionally-agreed health standards, a new health “nationalism” may emerge in which movement of people across borders will be severely restricted. The degree of restriction may, in turn, be related to the emergence of home bias with regard to health supplies.

This, in turn, may increase government support for so-called “national champions”, strategic industries or companies that are deemed essential for the security of the state and its citizens. These “champions”, in turn, would presumably receive the state’s protection from hostile foreign takeover, by definition leading to a balkanisation of global capital markets and, in turn, undermining the interests of shareholders (unless, that is, the “champions” become profit-hungry monopolies). In the process, the rules of international trade would be turned on their head: domestic security would trump international engagement.

Renewed political enthusiasm for safeguarding the incomes of “key workers” may have profound implications both for the distribution of income and wealth within nations and relations between nations, possibly requiring a sizeable increase in the tax burden on corporations, high earners and the wealthy. To raise such taxes may require worldwide income tax regimes for a country’s citizens (in line with existing US tax policy) and significant restrictions on the mobility of wealth and capital.

External consequences

The Global Financial Crisis had already created conditions for new brands of isolationism and protectionism. Covid-19 may do more damage. Admittedly, we are seeing a coordinated response in some areas echoing efforts made during the Global Financial Crisis. Scientific advances in the battle against Covid-19 are being widely shared and disseminated; the Federal Reserve quickly moved towards the establishment of international swap lines for US dollars, easing pressure on vulnerable currencies and capital markets elsewhere in the world; and the G20 has agreed a debt moratorium for some of the world’s poorer countries to provide additional financial space with which to battle against a common enemy.

In other areas, however, the situation is not so clear. A victory in November’s US Presidential Election for Joe Biden might help “dial down” some of the rhetoric that has disturbed relations between the US and China. With a relatively hostile Congress, however, this is hardly guaranteed. It is possible that the European Union agrees to common bond issuance in an attempt to “pool” virus-related financial risk across members of the Eurozone. At the time of writing, however, Germany, the Netherlands and Finland were steadfastly resisting. It could be that, once Covid-19 is under control, the World Health Organisation’s reputation will emerge unscathed, possibly leading to a series of newly agreed international health protocols. Yet, at this point, it’s just as likely that the WHO will end up being a useful scapegoat for nations keen to disguise their own failings regarding Covid-19.

All of this suggests that the risk of dislocated nationalistic responses in response to the pandemic remains high, particularly given emerging narratives regarding “national” struggle and “national” sacrifice. That, in turn, provides an unhelpful backdrop in assessing the longer term global economic outlook.

After the fall: a possible economic trajectory

In principle, the economic policy objective for any government facing Covid-19 is easy to state. Macroeconomic stimulus has to support otherwise bankrupt companies and otherwise-unemployed workers during the period of lockdown, in the hope that they can emerge into a post-virus world in which business can return to normal. It is the equivalent of building a “bridge” over the economic and financial crevasse created by Covid-19. Building bridges is a much better option than doing nothing but, nevertheless, there will be consequences:

- Levels of public debt will soar relative to GDP, in particular during the period of lockdown. For emerging markets with chequered financial histories, this may be particularly problematic.

- Bridge building will be more effective within nations than across nations.

- Some companies – primarily small and medium-sized enterprises – may opt to go out of business. As a result, of the millions of workers now losing their jobs, some will struggle to find gainful employment when lockdowns end.

- The uncertainties associated with Covid-19 lockdowns will undermine investment. Productivity gains may, as a result, be lower.

- “Insurance” against future pandemics (and, in the absence of an effective vaccine, the return of the current virus) will inevitably be in high demand. Such insurance will, in the near term, divert resources to what might loosely be described as “non-productive” areas. Global supply chains are likely to be attenuated with home bias becoming a much bigger influence, marking a part-reversal of the efficiencies gained over the last half century.

Source: Refintiv Datastream

The burden of debt

Fortunately, persistently-low interest rates have kept debt-interest burdens at relatively low levels, suggesting that there is plenty of room for governments to borrow a lot more in coming months, particularly in developed nations in which central banks are credibly able to “underwrite” additional debt issuance.

What happens, however, when the virus is finally in retreat and economic growth has stabilised? How will nations cope with higher levels of government debt? One way to consider these questions is to recognise that we are collectively borrowing from our future selves. The more successful that borrowing proves to be in safeguarding economic activity, the more easily digestible will be the higher future debt burden: the denominator in the debt/GDP ratio will rise quickly. If, on the other hand, the additional borrowing is unable to prevent wholesale economic ‘scarring’, the greater the future political challenge will be in deciding who ultimately has to repay the extra debt.

That debate was particularly active after the Great War (1914−18), partly because countries emerged from the conflict (and the Spanish flu which followed shortly thereafter) in differing states of financial health. For Germany and Austria, burdened with reparation payments in addition to the costs of the war itself, inflation became the inevitable escape mechanism. For the UK, a desire to stick to the pre-war “rules of the game” persuaded policymakers to rejoin the Gold Standard at the pre-war exchange rate, a decision that imposed a huge internal devaluation on the UK economy. Other countries eventually ended up defaulting (although those defaults may have had more to do with the consequences of the Great Depression at the beginning of the 1930s than with the First World War itself).

Put another way, the “scarring” after the Great War turned out to be far worse than after the Second World War. One reason for the difference was the willingness after the Second World War to put differences to one side – most obviously through the Marshall Plan and the creation of a wide range of “rule-setting” international institutions – in a bid to build a future in which both victor and vanquished could flourish. It’s not clear whether that spirit of cooperation can easily be resurrected in an environment that provides uncomfortable reminders of earlier periods of isolationism and protectionism.

The technology wildcard

Wartime may be deeply unpleasant but it can also be a catalyst for remarkable technical progress. It may be that the war against Covid-19 will also lead to significant technological change that, in time, will trigger major shifts in how societies operate.

However, the emphasis on “national” security may mean that technology is increasingly used to shorten global supply chains and encourage ‘reshoring”, suggesting a growing income gap between already-industrialised economies and those in danger of being left behind. As I argued in late-January:

“Instead of dispersing opportunities, skills, and knowledge to workers around the world, capital could stay home. Wealthy countries would invest in robot technology. Those who owned capital — or the ability to tax capital — would prosper. Those who supplied only labour — particularly for jobs that are easily automated — would suffer. Big chunks of Asia, much of sub-Saharan Africa, and large parts of Latin America might be left behind as the richer countries, in effect, build gated communities.

Arguments for free trade depend on the idea that economic and financial links between countries create win-win outcomes. If the rise of the robots removes the need for global supply chains — or at least shortens them — it becomes easier to support isolationist policies. The institutions that helped set the international rules of the game since the end of World War II would dissolve or be supplanted. Regionalism and nationalism would become more likely default outcomes.”

Put another way, technology may have been a driving force behind late-20th Century globalisation but, particularly in the light of Covid-19 and the enhanced desire for national “security”, technology can equally be used to enforce separation.

Conclusions

In sum, the likelihood is that, even after a strong rebound in economic growth later in 2020 or, more likely, in 2021, there will be no return to business as usual. Political and social priorities will likely shift, with a greater emphasis on health security and a reduced weight on near-term economic gains (in much the same way that, following the Global Financial Crisis, financial stability was prioritised over economic growth). Supply chains will be shorter than before, particularly in the areas in which national security is emphasised, with a loss of near-term economic efficiency. Companies may be less “international” than they once were, fearing both the return of cross border lockdowns and sudden shortfalls of available labour in key offshore centres. Nations will be more insular and the world as a whole more disconnected than it has been in many years.

Stephen D King is an economist and writer. His last book, Grave New World (Yale), is now available in paperback.