Winter 2003

Corporate Social Responsibility: More Than Apple-Pie and Motherhood?

There is hardly a boardroom in Britain, or indeed of any significant international company, which is not wrestling with the question of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), both in terms of its obligations and its boundaries.

We live in a mistrustful world — with an instant web of communication which has accelerated the velocity of embarrassing information, making double standards

impossible, putting corporations on the defensive and providing their critics with ammunition. Francis Fukuyama’s ‘End of History’ may have left capitalism as the only available economic system still standing but, if so, it is under closer critical scrutiny than ever before. This is not merely from un-reconciled Marxists and the sea-green incorruptibles of the environmental movement — who often seem to dislike trade and industry per se — but also from a much wider spectrum of critics who balk at markets and liberalisation as the universal answer to every problem.

So business leaders find themselves mistrusted, along with politicians and journalists. And unsurprisingly since business, as Fukuyama also pointed out, depends on trust and mutual consent they are concerned to improve their reputations and relationships.

Maybe what we are seeing is capitalism trying to accommodate itself to the inevitable social pressures of being the monopoly economic system and therefore subtly adapting itself or, more prosaically, being forced to give a better account of itself. And this at a time when the age of deference is over and there is a widespread mood of cynicism, fuelled to a great extent by the media.

Either way, companies feel the pressure of external expectations, whether from their consumers, customers and investors, or from media, regulators and government. Among the responses to these external pressures to perform more responsibly are: a desire to build and secure corporate and brand reputation, of which social and environmental performance is an increasingly significant component; an acknowledgement of the need to work with governments who in turn are subject to electoral pressure; and an awareness of the need to respond to the significant shift in the demands of investment institutions on these issues, the trend towards ‘ethical’ or ‘socially responsible’ investment.

Yet the real crux in moving CSR from the public relations department to the management team as a whole is the extent to which these and other pressures are internalised so that a business case, based in a competitive world on comparative advantage, can be made. Can companies ‘do well by doing good?‘

Something which assists the business case for CSR are internal drivers as well as external pressures: for instance attracting and retaining better employees; managing risk better; securing product advantage; or becoming a preferred supplier, contractor or developer.

If CSR is to represent a substantive change of approach rather than a PR gloss, it will invariably be because of the combination of board leadership and management ownership. If CSR is to be integrated into the way every manager does his or her job, and is trained and motivated to do it, it will only be because the company as a whole has decided that this is how it does its business. And that in turn is because the company and its leadership has become convinced that this is the best way of creating long-term value. In this, compliance with various external codes seems less important than the company working out for itself where it stands and what should be expected of it.

It is worth noting here a significant difference in approach between US and European companies. The US, with its continuing record of outstanding business success, albeit marred by periodic excesses, has a simple model: the invisible hand moving in its mysterious way, constrained when absolutely essential but not otherwise by the law, and softened by an impressive record of philanthropy. Compliance with the law is secured by an army of lawyers but the working assumption is that which is not forbidden is allowed. The orthodoxy of neo-classical liberal economists has been transformed into a system of faith so that the response to an Enron-type scandal is not a crisis of faith but a change in the law such as Sarbanes-Oxley.

Yet it is equally noteworthy that those US corporations most engaged on a long-term basis with the wider world, companies such as General Motors, P & G, Dow or Du Pont, have been willing to adopt a more heterodox approach, moving more readily to compliance-plus models of CSR, being noticeably more engaged than their peers with the social context of what they do, and being more ready to sign up for such commitments as Kofi Annan’s Global Compact and/or The Sullivan Principles.

Of course whether in the US or Europe, CSR has been evolving, from health and safety, to the environment, and in the past decade to complex social issues. Models of performance such as the Triple Bottom Line approach are helpful insofar as they focus managers on the real world trade-offs between economic, environmental and social ‘goods’. But they are potentially misleading if they suggest some choice-free world where all three goods can be simultaneously maximised. Sustainable development, as governments find, let alone companies, is all about choice and priorities.

So is CSR simply the latest management fad enjoying its brief moment in the sun, or a real paradigm shift in corporate policy and practice?

Some 60% of FTSE 250 companies now report on their environmental performance and, something which is a great deal more difficult to define, 40% report on their social performance. Transparency and accountability, reflected in well-audited performance, are clearly both evidence of and a competitive driver towards commitment.

It is noteworthy, however, how few companies report well on the third leg of the sustainable development tripod, which is after all their main raison d’être: their economic performance. It may well be that some of the mistrust felt by society as a whole towards its business component lies precisely in a tendency by companies to articulate their core function almost solely in financial terms rather than in human economic terms: jobs created, innovation and invention, taxes paid, training and development undertaken etc.

The question which presents most difficulties in discussing the future of CSR is the definition of the boundaries between the corporate and governmental spheres. In Russia for instance, following Fouquet, the state has almost said “enrichissez-vous” to the oligarchs, on the condition that they pick up the paternalistic social obligations of the old Russian state-owned enterprise.

In the knowledge that low-tax parties are more likely to win elections in middle class societies even Western governments have been tempted towards the same Faustian pact with business — a pact that business would be wise to resist. Yet in Third World countries where funds are limited and state provision negligible, it is almost inconceivable that corporate responsibility to employees, families and neighbours should not extend to cover some benefits traditionally within the sphere of government.

Human rights and security issues pose similar problems of definition for the responsible company operating in countries where governance is weak, and where the divisions between civil and military power is completely porous.

We can therefore forget any notion that the adoption of clear policies on these issues of CSR is the end of the matter for the responsible company. It is precisely in the general adoption of the policies by the entire management at all levels, and then in their application to tricky real world situations, in bad times as well as good, that the robustness of the policies, and the firmness of the intentions behind them, are going to be judged.

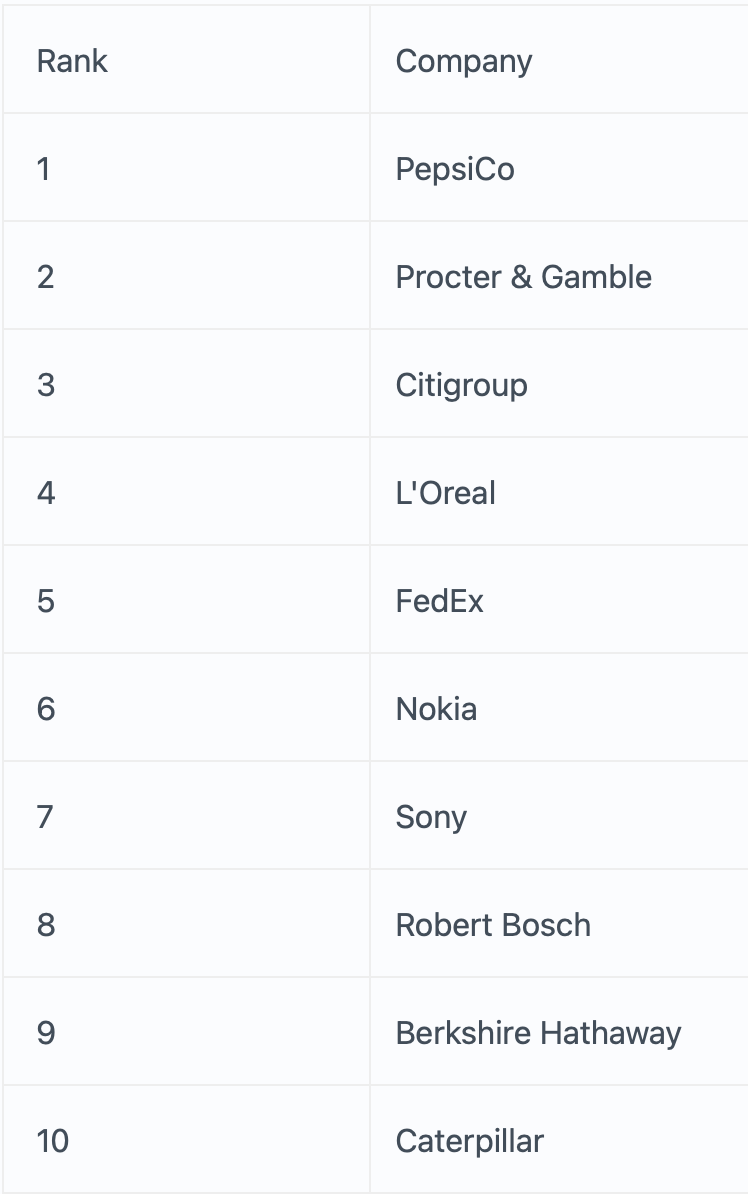

Top ten globally most admired companies in innovativeness

Criteria: Innovativeness, Quality of management, Employee talent, Financial soundness, Use of corporate assets, Longterm investment value, Social responsibility, Quality of products/services, Globalness

Source: Fortune Magazine

MOST GLOBAL BRANDS |

Lord Holme of Cheltenham is Special Advisor to the Chairman of Rio Tinto and Chairman of the International Chamber of Commerce Environment and Energy Commission