Winter 2024

Europe in the Shadow of Armageddon

In Berlin on 12 December 1989, in a ground-breaking speech to the Foreign Press Club, the American Secretary of State James Baker III spoke of a new departure for the United States and a new and united Europe. “Working together, we must design and gradually put into place a new architecture for a new era,” he proclaimed. It was a month after the Berlin Wall was breached, Germany was on the way to unification and Soviet forces on the point of withdrawal from Eastern Europe.

James Baker in effect was declaring the arrival of the peace dividend, the slogan rapidly embraced by US President George Bush, and his British compatriot Margaret Thatcher. The speech wound up with a flourish: “an end to the unnatural division of Europe, and of Germany, must proceed in accordance with and be based on the values that are becoming universal ideals, as all the countries of Europe become part of a commonwealth of free nations.”

The new peace would mean an end to war in Europe, hot or cold, local, regional or global in impact.

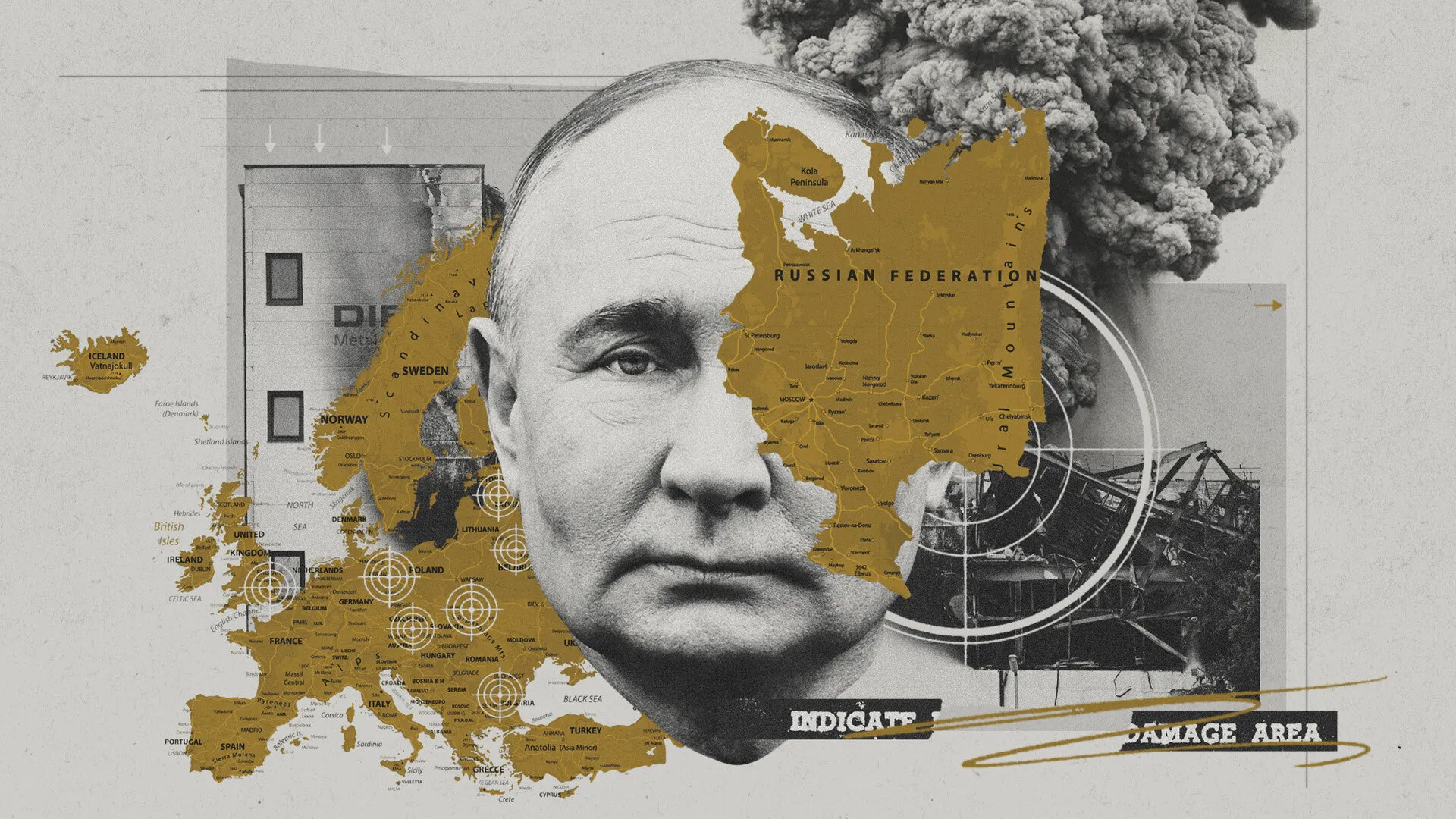

Almost a quarter of a century later, Vladimir Putin, undisputed leader of the Russian Federation addressed the world on state television with a warning – that America and its allies were on the point of “pushing the whole world into a global conflict.” The Ukraine war had been raging for over 1,000 days, still with no clear outcome and winner. Russia had lost up to three quarters of a million killed and injured. With the hundreds of thousands of soldiers and civilians from Ukraine killed and maimed, the war to date had produced well over a million serious casualties, with half the civilian infrastructure of Ukraine trashed by indiscriminate shelling and bombing.

Putin was enraged at the American and British governments allowing Ukraine’s forces to use their depth bombardment weapons, the ATACMS rockets from America, and the air-launched Storm Shadow from the UK. Both can reach up to 250 kilometers to attack concentrations of reserve forces, dumps and supply convoys, inside Russia. In reply Russia fired an Oreshnik intermediate ballistic missile, with 64 independent warheads and a nuclear capability. More to the point was the scatter-gun rhetoric of Putin’s speech explaining his move, and what it suggests about the changing nature of war, its causes and practice, on a global scale.

Not only had the war in Ukraine been provoked by the western alliance, he claimed but it was part of an American-led “plan to produce and deploy intermediate- range and shorter-range missiles in Europe and the

Asia-Pacific region.” With Russia’s new reliance on North Korea, this holds the prospect of a widening of the Ukraine crisis into Southeast Asia – and a possibility of reawakening the ‘frozen’ conflict of the Korean War of the 1950s.

War did not leave the European neighbourhood. Across the world conflict had changed its nature and complexion in the 25 years between Baker’s Berlin speech in December 1989 and Putin’s threat to turn the Ukraine war global in late November 2024.

Warfare in 1989 was conceived largely in three dimensions: land, sea and air. Satellites had begun to change communications on the battlefield, in strategic command, and propaganda and reporting. The fall of the Berlin Wall on 9 November 1989 was one of the first global events to be reported in real time, as it happened, by satellite television and radio broadcasting.

Today the pervading sense is of neither war nor peace

By the outbreak of the second phase of the war in Ukraine, with the invasion from Russia on 24 February 2022, warfare would be conducted in six dimensions: in space, cyberspace, and the new information sphere. Ahead there is the seventh dimension of quantum physics, one of the big unknowns of 21st century society. According to some, such as Carlo Rovelli, the influential Italian thinker, it will turn the traditionally accepted Scientific Method pioneered by the likes of Isaac Newton, on its head.

Today there is a pervading sense of neither war, nor peace, of hostile acts against civilian communications infrastructure, interruption of vital supply lines, enhancing a sense of insecurity in food and energy provision. New buzz words appear such as ‘the grey zone’ – areas of disguised hostile activity. Old buzz words are retooled, like ‘hybrid’ or ‘asymmetric’ warfare, meaning the use of traditional tools in unconventional ways, suicide bombing vests, improvised remotely triggered bombs, IED’s built for $10 in Iraq and Afghanistan, civil airliners driven into buildings in kamikaze attacks, as in the bombing of the World Trade Centre on 9/11.

Wars did not cease in 1989 for even the main contributors to the Nato alliance. Saddam Hussein invaded and seized Kuwait the following August – and it took Desert Storm – and the first widespread use of satellite-guided bombs, to get his forces out. That same year, 1991, saw the beginnings of the wars of the dissolution of Yugoslavia, starting in Slovenia and Croatia, and moving to the bloodier conflict in Bosnia from 1992 to 1995, with a further round of guerrilla warfare and banditry in Kosovo at the close of the decade.

Another phenomenon had arisen in the wars in Yugoslavia, though hardly noticed at the time, a new form of Islamist Jihadi terrorism and subversion. It came from the Middle East and grew from the teachings of the likes of Sayyid Qutb and movements such as the Islamic Group in Algeria and Egypt. In this, Osama bin Laden’s Al Qaeda became the brand leader, but was only one among many groupings of Islamic militants bent on destruction and self-immolation. It was a common thread to wars, insurrection and civil wars following the 9/11 attacks – the high point of al Qaeda military action – in Afghanistan, Iraq and across Syria and the fertile crescent.

The technology of war and its social impact has changed dramatically between 1989 and 2024. The internet arrived in the 1990s, and with it the mobile phone. By 1995, the end of the siege of Sarajevo in September, mobile phone networks were in their infancy. In Sarajevo the range of the phones was limited to a few kilometers – with the aid of a Swiss Sim card traded through the street mafias.

Less than ten years later, Afghanistan enjoyed mobile phone cover across 80% of its territory, despite never having a landline phone system.

Source: The Week

By the outbreak of the second phase of the war in Ukraine, with the invasion from Russia on 24 February 2022, warfare would be conducted in six dimensions: in space, cyberspace, and the new information sphere. Ahead there is the seventh dimension of quantum physics, one of the big unknowns of 21st century society. According to some, such as Carlo Rovelli, the influential Italian thinker, it will turn the traditionally accepted Scientific Method pioneered by the likes of Isaac Newton, on its head.

Today there is a pervading sense of neither war, nor peace, of hostile acts against civilian communications infrastructure, interruption of vital supply lines, enhancing a sense of insecurity in food and energy provision. New buzz words appear such as ‘the grey zone’ – areas of disguised hostile activity. Old buzz words are retooled, like ‘hybrid’ or ‘asymmetric’ warfare, meaning the use of traditional tools in unconventional ways, suicide bombing vests, improvised remotely triggered bombs, IED’s built for $10 in Iraq and Afghanistan, civil airliners driven into buildings in kamikaze attacks, as in the bombing of the World Trade Centre on 9/11.

Wars did not cease in 1989 for even the main contributors to the Nato alliance. Saddam Hussein invaded and seized Kuwait the following August – and it took Desert Storm – and the first widespread use of satellite guided bombs, to get his forces out. That same year, 1991, saw the beginnings of the wars of the dissolution of Yugoslavia, starting in Slovenia and Croatia, and moving to the bloodier conflict in Bosnia from 1992 to 1995, with a further round of guerrilla warfare and banditry in Kosovo at the close of the decade.

Another phenomenon had arisen in the wars in Yugoslavia, though hardly noticed at the time, a new form of Islamist Jihadi terrorism and subversion. It came from the Middle East and grew from the teachings of the likes of Sayyid Qutb and movements such as the Islamic Group in Algeria and Egypt. In this, Osama bin Laden’s Al Qaeda became the brand leader, but was only one among many groupings of Islamic militants bent on destruction and self-immolation. It was a common thread to wars, insurrection and civil wars following the 9/11 attacks – the high point of al Qaeda military action – in Afghanistan, Iraq and across Syria and the fertile crescent.

The technology of war and its social impact has changed dramatically between 1989 and 2024. The internet arrived in the 1990s, and with it the mobile phone. By 1995, the end of the siege of Sarajevo in September, mobile phone networks were in their infancy. In Sarajevo the range of the phones was limited to a few kilometers – with the aid of a Swiss Sim card traded through the street mafias.

Less than ten years later, Afghanistan enjoyed mobile phone cover across 80% of its territory, despite never having a landline phone system.

Satellite guidance and communications enhanced the use of remote pilotless vehicles, UAVs or UCAVs, such as the Predator and Reaper. They became cheaper and more focused. Loitering munitions could hang around a target for several hours before striking. Early Israeli ‘kamikaze’ one-way loitering drones proved decisive in

Azerbaijan’s incursion in Nagorno-Karabakh in late 2020. They have been decisive, too, in the contact battles in Ukraine since 2022 and Israel’s incursion into Lebanon and Gaza from 2023.

The most effective use of the internet in covert or ‘grey zone’ activities has been in the deployment of a wide range of tools and tricks in cyberspace. Malware, bots, Trojan Horses and the like are now deployed by the hour against a whole range of targets from the US National Security centres, the Pentagon, airports, airline communications, and Starbucks and UK National Health hospitals and data bases. Notorious among many, was the deployment of Stuxnet malware to disrupt Iran’s nuclear industry’s centrifuge centre at Natanz in around 2010. The origins and development are shrouded in official obfuscation and secrecy, but most conclude it was concocted in Israel and the US by a variety of specialist agencies, among them Israel’s Military Unit 8200.

The UK experienced a series of ‘ransomware’ attacks in 2017, which continue, and are subjects of repeated warnings from the National Cyber Centre.

They are a key element of ‘grey zone’ activity – hostile acts or provocations through social media and third-party propaganda, which can be denied. The attempt to kill

the double agent Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia in Salisbury with Novichok in Salisbury seems typical of the genre, only the activities of the Russians was so ill disguised and crude.

The tempo of such operations has increased hugely since the Russian attack on Ukraine two and half years ago – but so too have cyber actions from China. Despite the war in Europe, the turmoil in the Middle East and its spin offs in the attacks on global maritime commerce in the Red Sea from the Houthis, there is little sense of threat in countries like the UK, where support for defence and the military is low according to recent opinion polls.

“If only we could stop talking about defence, which most in government find off putting, and talked about resilience and security instead,” a young British general said recently, “we could get some realistic policy on a very present threat.”

The Ukraine war and Putin’s chosen path of perpetual aggression have generated a cluster of problems and challenges which should be fundamental to a defence, resilience and security strategy for major Nato partners like Britain – especially for the era of the second Trump presidency. It will present them with a hefty bill for national defence, at which countries like Britain baulk. The recently elected Labour Government seems bent on postponing raising defence spending to 2.5% of GDP, until they say they can get the books straight, and debt down. But at the end of 2024, a 3% expenditure on defence and security is barely sufficient to meet urgent needs for reform, according to a consensus of expert calculation analysis in Europe and America; some experts warn that in a worst-case scenario it would have to move to 5%.

Source: AI generated

The mixture of challenging elements is bewildering, a combination of traditional and thoroughly modern

warfare. Then there are the peripheral but serious threats, in cyber and communications and sabotage attacks on infrastructure. In the UK both the security services and the public seem ill-prepared for what is happening. The armed services are under manned, under recruited and almost deliberately underfunded. Some of the most

forward-thinking commanders and officials believe that a future security and resilience architecture depends on a more direct partnership between the security service and agencies and industry and enterprise – and through them to encourage societal resilience and responsibility.

This might involve direct sponsorship for cadet forces and apprenticeships for young men and women to study and qualify for availability for public service. It does

not necessarily imply these should be mere recruiting sergeants for the armed services. There are roughly twice as many cadets as soldiers in the British Army. Those who have been cadets perform and achieve notably better in their careers than their non-cadet peers.

In Ukraine the fighting is brutal, with the attrition rate of Russian forces round Karkhiv in the autumn of 2024 worse than the ground wars of Vietnam in the 60s, the Western Front in 1914–1918, and the Eastern Front

in 1941–45. The rate of destruction of soldiers is a proportion of 11 per unit area – whereas Vietnam and the Somme and Ypres Salient from 1915–17 was about six. This is according to British military intelligence analysis – the killing rate is matched only by that of the destruction of the Chinese infantry ‘wave’ attacks at the end of the war in Korea from 1952–53.

Matériel as well as men have been consumed at rates unimagined in the planning cells of most Nato allies. Drones have made infantry manœuvre transparent – any offensive move on the Donetsk front is spotted in under two minutes and struck by artillery and rocket fire within five.

The sense of distracted times contributes to a pervasive mood of unease

Around this there is the ‘asymmetric’ or ‘hybrid’ activity of subversion and sabotage, by Russian forces such as the GRU, and proxies including organised crime operatives. Air freight warehouses have been hit by firebombs – probably flown in air cargo consignments – across five countries. In September 2022 explosions ravaged two

of the Nord Stream oil pipelines from Russia to Germany that were closed for good as a result. The identity of the

saboteurs was never established definitively by Swedish intelligence – and there is a strong hint that the operation was outsourced to organised crime.

In late 2024 the Irish Coastguard and Navy alerted the UK and EU allies about the suspicious activity of the Russian survey ship Yantar in Dublin Bay and later off Cork close to major communication hubs to the UK and Europe.

At about the same time the Danish Navy and Swedish coastal protection service detained the Chinese freighter Yi Peng 3, carrying Russian fertilizer. Satellite surveillance showed that it dragged its main anchor for 100 nautical miles deliberately cutting two major communication cables between Finland Germany. The Russian captain is accused of being tasked in the port of departure, Ust- Luga on the Baltic. On the way, its transponders were switched off so it couldn’t be detected. But satellite imagery shows it travelling very slowly as it dragged its anchor.

The sense of distracted times, that Europe and the world are oscillating between a new war and uneasy peace contribute to a pervasive mood of unease.

European allies are being encouraged by Nato to spend more on defence, and some, Poland, Finland, the Netherlands, seem more prepared than others. The new transactional presidency of Donald Trump means less America in Europe and Europe must do more for itself.

This brings us back to the speeches of Baker and Putin. One was as full of hope as the other was of menace. In 1992 Francis Fukuyama published “The End of History and the First Man.” The message was not that history had ended but a new era of prosperity, consensus and triumph of liberal democracy and free enterprise was at hand. We had entered the world of the peace dividend.

That era has now come to an end, and the future is seen not with hope, but fear and apprehension. This is the conclusion of Ivan Krastev in his recent podcast with Yaschir Mounk, in which he states the need for a renewed approach to security and resilience.

It should not now be simply a story of existential despair – that we have drifted form the times of hope and prosperity heralded in 1989 to a quagmire of

hopelessness and existential gloom in our own time. But we must be alert and prepared for action today.

The nuclear shadow that appeared to be dissolving at the end of the last century – indeed, whose demise in a series of new international agreements was forecast in James Baker’s speech – is now returning. New START strategic arms reduction talks are stuttering, and the Chinese are reluctant to participate at all.

As Vladimir Putin boasted, Russia is developing new nuclear capable intermediate and hypersonic weapons, and the Middle East seems on the threshold of a new surge of nuclear proliferation. More worrying is the potential abuse of civil nuclear power threatened by Russia targeting the chain of nuclear plants across Ukraine, starting with Zaporizhzhia, the largest nuclear power generating plant in the whole of Europe. The Chernobyl meltdown in 1986 is still the worst ecological disaster from a civil nuclear accident in European, if not world, history. Could it happen again? The Russians have shown no compunction about triggering a major ecological disaster when they deliberately breached the Kakovka Dam in June 2023.

Perhaps we have basked in the slipstream of the peace dividend notion for too long.

As Sweden and Finland understood in their recent civil preparation and security exercises, we need to look at resilience and security as an activity for society and not just the business of the professionals in the military, the spies and the cyber spies.

The threat of war and conflict is taking many different forms, and we must take heed, publicly and privately – the business of the government and the citizen in equal measure. As an earlier US president, FDR, said in his first inaugural, “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself – nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyses needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.”

Vladimir Putin, as his ambassador to London declared publicly to Sky News, is at war with the West. The main task now is to deflate such rhetoric, very much the propaganda media currency of our times, and give peace a chance.

Robert Fox is Defence Correspondent for the London Evening Standard and author of The Inner Sea: The Mediterranean and Its People.