Winter 2017

Globalisation’s Ebb and Flow

Only a handful of years ago, many in the West regarded globalisation as ‘one-way traffic’. As Tony Blair famously put it in his 2005 Labour Party conference speech “I hear people say we have to stop and debate globalisation. You might as well debate whether autumn should follow summer.” Subsequent events suggest that Blair was wrong. Globalisation is by no means inevitable. Nor does it depend on technological advance alone. Ultimately, the degree to which different parts of the world connect with each other depends on the ideas and institutions that form our politics, frame our economies and fashion our financial systems. When existing ideas are undermined and institutional infrastructures implode, no amount of new technology – or, indeed, economic ‘rationality’ – is likely to save the day.

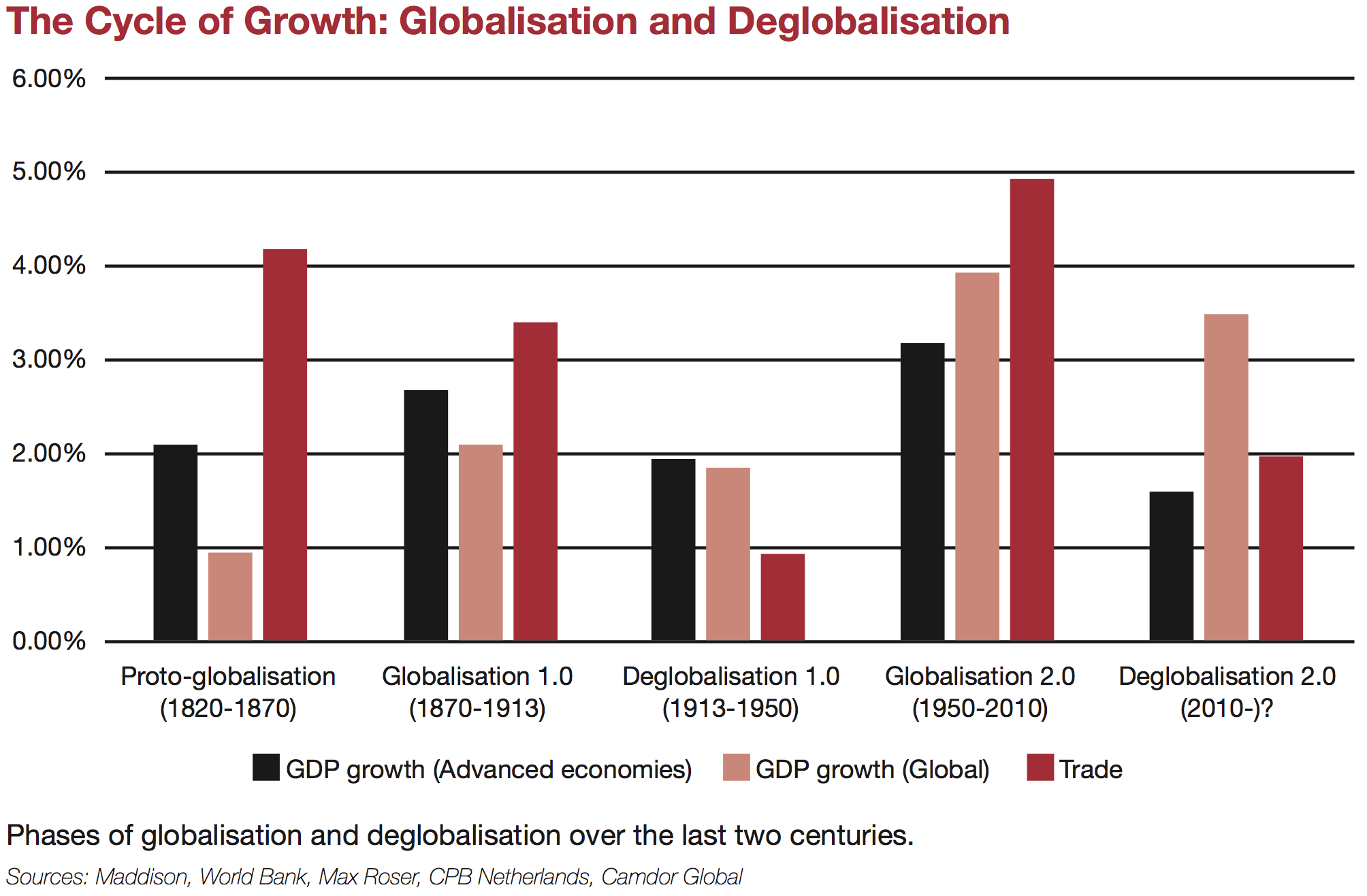

Globalisation has always waxed and waned, at least as far as the ‘known world’ is concerned. Ancient Rome offered one version of continental interconnectedness, even if it was more dependent on military ambition and slavery than on voluntary exchange. Islam’s spread from the Middle East via North Africa into the Iberian Peninsula created a single market in goods, services, capital and people, a forerunner of the values enshrined within the European Union. China at the beginning of the 15th Century arguably had the most powerful navy in the world and used it to create economic linkages with much of Asia, offering an early version of ‘Belt and Road’. The British Empire provided its own version of globalisation in the 19th Century, this time dependent on a strange mix of free trade philosophies and coercive imperial ambition. Each of these previous globalisations ultimately ended up in failure.

The end of the West’s dream

Today, globalisation – or at least the West’s version of globalisation — is once again in trouble. The western model arguably reached its apotheosis in 1989, the year in which the Berlin Wall came down and Francis Fukuyama wrote his famous paper declaring ‘The End of History’. With Soviet-style Communism in retreat, it appeared that the West had won.

The Cold War was over and, by implication, liberal democracy and free market capitalism had emerged triumphant. Authoritarian regimes had clearly failed. As the West’s supposedly universal values spread to other parts of the world, economic growth elsewhere was bound to accelerate. After all, only the yoke of Communism had held countries back. And as growth elsewhere picked up, so the West would also become richer: exporters would discover a host of wonderful new opportunities that, in turn, would lead to stronger investment, rmer employment and higher wages.

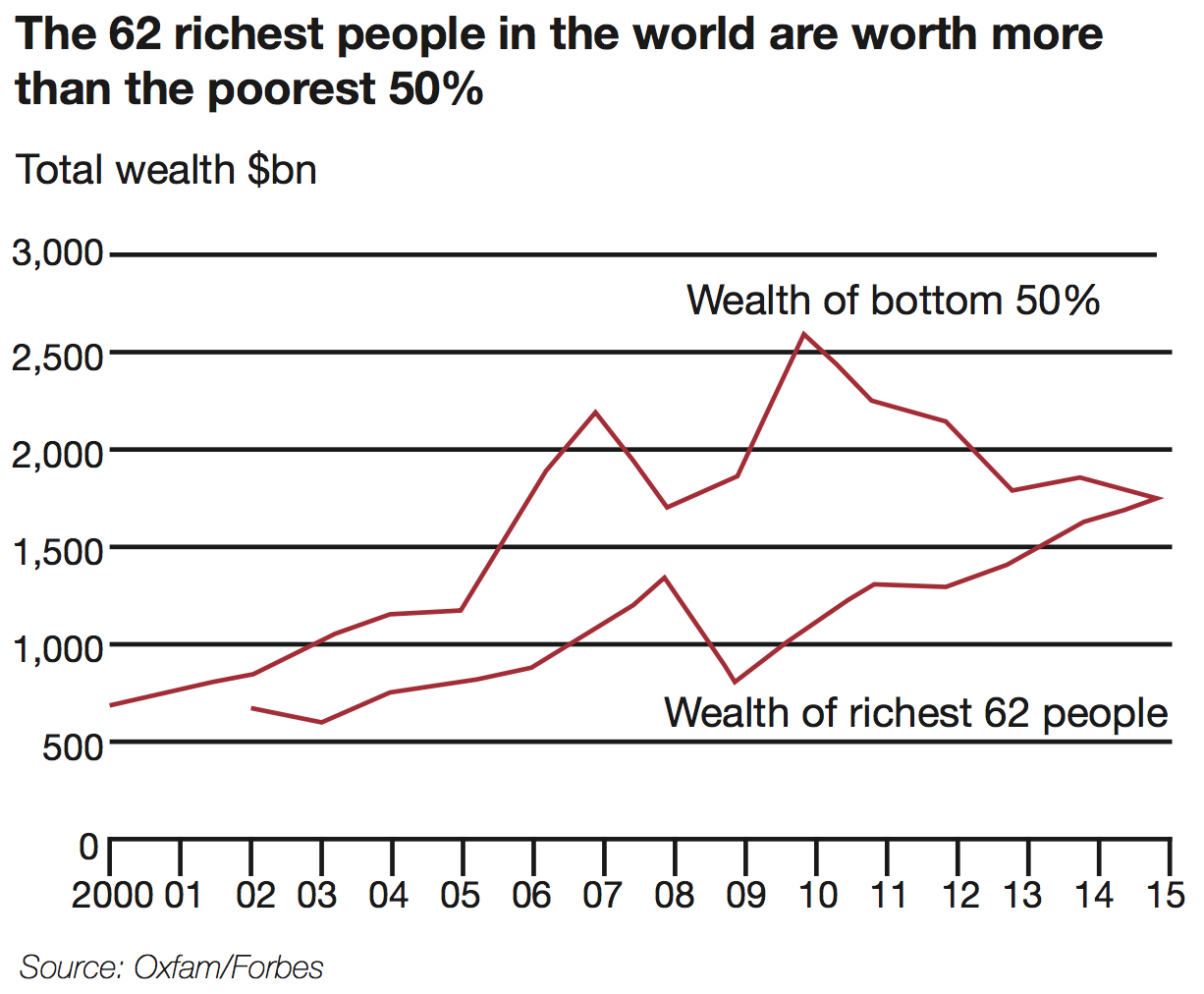

Since then, however, the West’s love a air with globalisation has soured. China has enjoyed unprecedented economic success, seemingly undermining the claim that liberal democracies alone are capable of driving living standards dramatically higher. Western economic growth, meanwhile, has completely stalled: for many countries, economic activity is now between 10 and 25 per cent lower than had been projected before the onset of the global financial crisis (which, itself, was something of a misnomer: in hindsight, the crisis was more a problem for the West than the rest). Income inequality has unexpectedly risen, creating a new narrative of ‘winners and losers’. Faced with revenue shortfalls and disappointing wage growth, the West’s politicians and voters have begun to wonder whether earlier claims about globalisation were all they were cracked up to be.

Why globalisation is the natural political scapegoat

To be fair, there are other explanations for the West’s woes. Robotics and artificial intelligence are making inroads into parts of western labour markets that, hitherto, were regarded as immune to technological advance. Educational failures have contributed to a decline in numeracy and literacy standards, at least when compared with the great strides being made in other parts of the world, notably East Asia. A more sclerotic housing market – in part a hangover from the global financial crisis – has contributed to a reduction in regional mobility, leaving people trapped in neighbourhoods that offer few prospects for economic rejuvenation.

Yet, whatever their merits, these explanations are difficult to deal with politically. Our leaders cannot easily stand in front of an incoming technological tide and, in the manner of King Canute, command its reversal. They cannot simply wave their wands and magically improve the life chances of those whose education was simply not up to scratch. And they cannot easily turn those trapped in areas of economic decline into budding tech entrepreneurs.

What politicians can do, however, is change the narrative. And that is precisely what has happened, notably in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. More than anything, the events of 2007 and 2008 appeared to suggest that global free market capitalism was inherently unstable and prone to sudden and painful upheavals that could leave many people in a position of intense economic vulnerability (Karl Marx, it turns out, knew a thing or two after all).

The old ‘left-right’ debates have suddenly become a lot more complicated. It’s no longer enough to declare your support for the welfare state, the freedom of the individual, the benefits of public provision or the need for a lower tax burden. The new politics is much more about what might loosely be described as ‘globalisation’ versus ‘isolationism’. And it cuts across political lines. Bernie Sanders, who narrowly lost out to Hillary Clinton in the battle to win the Democrat nomination for the 2016 Presidential Election, made the remarkable claim that “The global economy is not working for the majority of people in our country and in the world. This is an economic model developed by the economic elite to bene t the economic elite. We need real change”. In making this (false) assertion, Sanders revealed himself to be on the same side of a globalisation ‘fault line’ as Donald Trump with his ‘America First’ rhetoric.

Rejection of globalisation is not con ned to the US alone. Although many on the UK’s Conservative right look forward to a globalised free market nirvana following Britain’s timetabled 2019 departure from the European Union, the reality is that many of those voting for Brexit were motivated more by a desire to restrict immigration and to ‘take back control’, a reclamation of sovereignty that, if anything, represented a retreat into the sanctity of the nation state and, thus, an escape from the competitive rigours of globalisation. To the extent that trade is increasingly conducted nowadays according to the rules and strictures of regional agreements on standards and regulations, the UK’s ability to flourish in a post-Brexit world may be seriously curtailed if a constructive trading arrangement with its – spurned – near neighbours proves impossible to negotiate.

Macron’s hope and the European reality

Admittedly, with Emmanuel Macron’s victory in the French Presidential Election, it might be tempting to conclude that anti-globalisation sentiments are peculiarly Anglo-Saxon. Macron, after all, talks about building a more integrated European Union, including the creation of a European Finance Minister who, in time, might craft a federal Eurozone tax system that, like its American equivalent, would channel revenues from wealthy regions to those facing greater economic hardship (the people of Massachusetts unwittingly donate some of their tax dollars to those facing privation in, for example, Mississippi). Yet it’s difficult to ignore the sovereignty problem. Why, most obviously, would German voters opt for a system that might require them to offer financial support to parts of southern Europe on a semi-permanent basis (an outcome that now seems even less likely given Angela Merkel’s weakened position in Germany thanks, in part, to the return of far-right nationalist pressures)? And given the drop in Macron’s approval rating since he assumed power, is his own position as strong as many claimed at the time? After all, a marginally different voting pattern in the first round of the presidential election could have triggered a second round battle between the far right’s Marine Le Pen and the far left’s Jean-Luc Mélenchon. Macron’s efforts would then have been con ned to a footnote in history.

In any case, the focus on the Franco-German alliance, important though it is, ignores changes taking place elsewhere in Europe: a new, white, Christian narrative emerging in Poland and Hungary; a separatist Catalonia attempting to pull away from Spain; an Italy where living standards have, remarkably, declined since the Euro’s formation in 1999 and where the constitution is being overhauled with unpredictable consequences; and a newly-assertive Russia that looks to destabilise, rather than support, its western neighbours. Underneath all of this is a sense that the EU’s four freedoms – the free movement of goods, services, capital and people – are, somehow, under threat. As they represent the ultimate institutional embodiment of globalisation, their rejection would also mark the return of the ‘them and us’ attitudes that prevailed during the interwar period, hardly the most encouraging of precedents.

Source: Oxfam/Forbes

Rival globalisations

The West’s retreat from globalisation doesn’t, in itself, mean that globalisation is dead. Rather, we’re witnessing the emergence of rival versions of globalisation, challenging the idea that a universal set of (Western) values exists. China, most obviously, is promoting its own version of globalisation by creating international institutions that, in many ways, hark back to the 1940s and Bretton Woods. As President Xi emphasised at the 2017 World Economic Forum in Davos, China is more than happy to pick up the baton of globalisation if others let it slip through their ngers. Through the creation of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, Beijing is doing exactly that. These institutions support a ‘Belt and Road’ vision that potentially offers ever-stronger linkages between China, its Asian neighbours and, in time, both Africa and Europe.

It’s very much in China’s interests to encourage this new version of globalisation. With the enormous economic success of its eastern coastal regions, it is easy to forget that China’s inland provinces have been left behind. The result is a divided economy, with levels of regional inequality far greater than in, for example, the US, the UK or across the eurozone. That needs to change. Building a new infrastructure that links China’s inland regions with the rest of Asia – in e ect, the creation of a new Silk Road – may prove to be China’s equivalent of America’s 19th Century westward expansion. Competing versions of globalisation – one in retreat, one advancing – are unlikely to be happy bedfellows, particularly given the contrasting political systems that underpin them. Democracy and autocracy cannot comfortably co-exist. At the fringes, where China’s expanding sphere of influence bumps into the West’s dwindling ambitions, the risk of con ict (economically, politically or even militarily) is likely to increase. Globalisation based on competing – as opposed to universal – values is likely to encounter frequent problems related to issues of ownership, intellectual property and, more generally, the rule of law. This, in turn, may leave the world increasingly divided, with the US, China and a newly assertive Russia eyeing each other with growing suspicion. For the UK and Europe, this creates awkward choices. Already, the UK hopes to do trade deals with countries and regions outside the European Union. This may be easier said than done if, for example, a bilateral deal with the US cannot easily sit with a corresponding arrangement with China, India and other Asian nations. As for the rest of Europe, it’s fast approaching a historical fork in the road. Will its future continue to depend on its linkages with an increasingly isolationist US or, instead, will it return to its pre-Columbus connections with the Middle East and Asia? Will the European Union survive in its current form or, instead, will the border between East and West yet again shift as the forces of authoritarianism make themselves felt in Eastern Europe?

A shifting East/West axis

Trade linkages through Asia are expanding, the Silk Roads of antiquity are being re-established and 21st Century institutions are being created in Asia to deliver new international ‘rules of the game’. The West, however, is in disarray. It blames globalisation for many of its woes, its politics are becoming increasingly insular and it is too often restoring to the language of ‘them and us’. Yes, the lights of globalisation are increasingly being turned on in Asia. From London to Limassol and from Warsaw to Washington, however, they’re in danger of being extinguished.

Source: Maddison, World Bank, Max Roser, CPB Netherlands, Camdor Global

The writer is an economist and author. His latest book, Grave New World: The End of Globalisation, The Return of History, is published by Yale.