Winter 2024

Inconvenient Truths of the Energy Transition

So, what is the Energy Transition? The greatest challenge, and possibly opportunity, facing mankind over the next several decades? Or a hoax? This article reflects on the facts, the challenges and the potential impact of the new US Administration.

The science is as clear as science can ever be; human activity over the past 200 years has increased the level of CO2 in the atmosphere by around 2500 billion tonnes, in turn this has warmed the planet by around 1.1 deg C and ‘business as usual’ is likely to lead to warming over 3 deg by 2100 and significant changes in our climate.

COP 21 in Paris in 2015 led to a global commitment to limit the ultimate temperature rise to ‘well below 2 deg C’, subsequently rephrased to pursuing efforts to limit this to 1.5 deg C. This broadly equates to the widely quoted ‘net zero by 2050’ target, where any remaining CO2 emissions are offset by capture and storage.

Annual CO2 emission rates are currently over 40 billion tpa, and CO2 equivalent tonnes (including methane and other gases) are over 50 billion tpa. The science suggests that looking forward from 2020 there was a remaining ‘carbon budget’ of around 500 billion tonnes, that could be emitted if ‘Paris’ and net zero are to be achieved, of which over 100 billion tonnes has already been produced.

As our energy systems produce 85% of emissions, and within that around 80% of primary energy is still derived from fossil fuels (coal, oil, gas), then we need to make huge changes to the way we consume and produce energy, changing our lifestyles as well as large parts of our economy. To meet the targets, fossil fuel use by 2030 has to reduce by around 40% (Energy Transition Commission analysis). Remaining emissions largely derive from land use, forestry and agriculture.

While some still dispute the science – including the US President elect who has indeed described the climate change agenda as a hoax on multiple occasions – and noting the numbers are estimated ranges rather than precise outcomes, the direction of travel is clear, and the scale of the challenge is immense.

The direction of travel is clear, the scale of the challenge immense

Most political and business leaders do accept the science, and many countries and businesses now have clear targets to achieve net zero by 2050. However, almost none have clear plans to achieve this goal, with resources allocated and using existing technology. This is leading to the setting of nearer term equivalent targets for 2030 and 2035 which help frame the nature of the challenge or opportunity, and the need for urgent action.

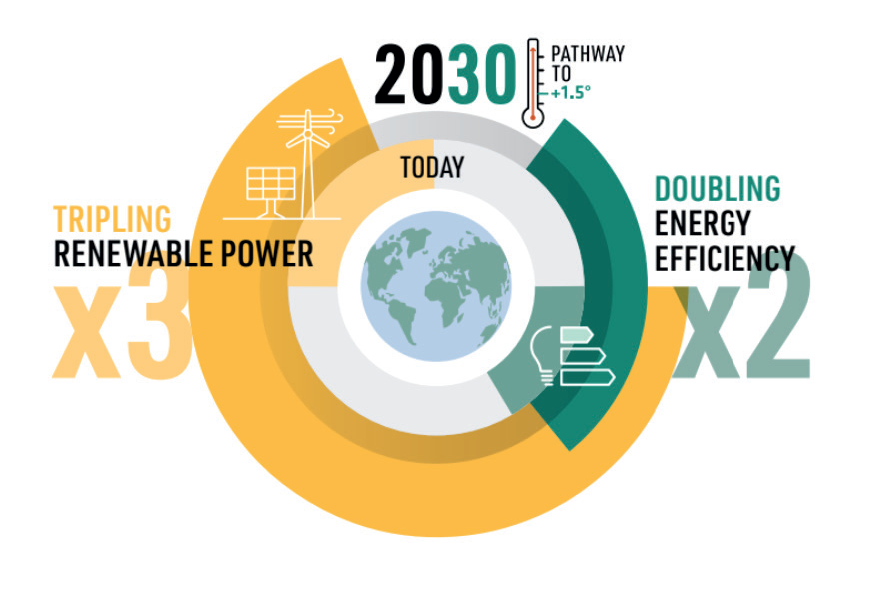

As Power and Mobility currently represent around 50% of total emissions, increasing and decarbonising electrification are key. Electricity currently represents only 22% of final energy demand, and this figure needs to increase to over 50% and maybe 60% by 2050, and total energy demand is likely to be considerably higher as well. Progress on renewable energy, wind and solar, is accelerating and investment is now well over $1 trillion pa. However, total installed generation capacity in 2050 needs to be around 5x 2020 levels, and almost all new capacity needs to be non ‑fossil fuel based. In the

short term, International Energy Agency data suggests installed renewable capacity needs to triple to 11 TW between 2022 to 2030. Transmission grids, storage and management systems need to grow at similar rates.

Electrifying demand is also essential, beginning with Transport. Electric vehicle mandates are driving adoption for light vehicles, market shares now >10% in the US, >20% in Europe and >40% in China. Industry executives

are keen in any case to make this change based on the logic that e‑vehicles ‘are fundamentally better cars anyway’. As costs come down and user concerns (range, recharge, resale) are addressed this trend is seen as globally inevitable, in future without subsidy. China is the de facto leader on cost and quality in this new and vital industry, and also well advanced in non-fossil fuel commercial vehicles, vans, buses and trucks.

Marine and Aviation transport, Industry and Buildings (around 40% of emissions) are more challenging in both technology and conversion costs, and increasing end user efficiency is also a high priority. New technologies – and industries — will need to be developed at scale, including green hydrogen and steel, sustainable biofuels, affordable heat pumps to replace gas boilers, and better efficiency management systems.

More sustainable forestry and agriculture practices will also be required, and this will likely need changes in consumer behaviour such as fewer dairy and meat products per head.

To achieve net zero requires all the above to happen at scale and speed. McKinsey estimates that up to $9 trillion pa is required to 2050, with this amount front end loaded, compared with perhaps $3 trillion actual spend in recent years. Some of this is in research and development, the vast majority is in new projects primarily in infrastructure, requiring financing and construction capacity to scale accordingly.

While Governments can prime the pump, much of this investment and certainly the management must come from the private sector and hence will require some form of acceptable return on investment. In the success case the potential for new ‘clean energy’ jobs and economic activity from the above is clear, the greatest investment and growth opportunity we have ever seen?

Paths to a successful outcome require many stars to align

So, there are paths to a successful outcome, or at least to go a long way on the journey to net zero. But they require many stars to align and a majority of actors to act in a coordinated and collaborative way. Governments, businesses and ‘society at large’ need to make material and lasting changes, to energy demand and supply.

Governments take precedence in this, as they set the frameworks in which private sector investment is encouraged, and societal acceptance is achieved.

Recent events including the pandemic and the war in Ukraine have reinforced the understanding that energy sources need to be secure and affordable, as well as clean. It is rare that a supply source meets all three of these criteria, with exceptions such as nuclear (France, Korea), hydropower (Norway, Canada), biofuels (Brazil), wind (UK), solar (Middle East, Australia) and geothermal (Iceland). All countries need to understand their best supply mix according to their competitive advantages.

In most countries, for most supply sources the primary challenge is affordability, but also social acceptance. Both have significant potential impact on the pace of change.

Source: AI generated

Governments need to demonstrate consistent and ambitious intent in their vision, support this with policy and resources, and to be honest and inspirational with citizens – and voters. We need to see ‘project enabling and market forming policies’, and in some cases capital to support developing technologies, and let the private sector source and allocate capital accordingly. To deliver the appropriate mix of physical assets, it is necessary to attract mobile capital at massive scale, and with some security of returns. This in turn requires long term stable policies, cross border alignments (e.g. carbon pricing) and incentives to change demand patterns.

Western Governments have a patchy track record on this benchmark. It is common to see medium-and-long term targets set and increased, with limited connection to viable plans, resources and supply chains. As this becomes clearer, there is a growing backlash against the ‘green agenda’, which cannot be addressed by platitudes such as ‘renewable energy is cheaper than any alternative’ particularly when this is often not true in the short to medium term. Given that the main short- erm blocker to Western projects progressing is planning permits, the need for Governments to build credibility and trust is paramount.

Can global policy develop in a constructive way? Globally the two elephants in the room are China and the US, not only the two largest emitters (approximately 45% of total emissions) but the two most powerful economies that could make a difference. And they may be about to take very different paths.

Taking China first. It is popular in the West to criticise China for its emissions, particularly its growth in coal power generation. The facts tell a different story, also noting that the West has in effect exported many of its emissions into China’s manufacturing sectors. In the 2010s China set out its intent to develop leading positions in emerging technologies and markets, several of which related to the Energy Transition. China now represents or controls more than 50% of the global production of solar, wind and battery capacity, and has now surpassed 50% of global electric vehicle production.

Source: Image source: Irena.org Digital reporting

In 2023 China installed 100 GW of both solar and wind generation capacity, both equivalent to more than the UK’s entire generation capacity from all sources. As a result, the country may already have peaked or at least plateaued its emissions (its 2030 target) and has realistic plans to progress towards its own 2060 target of carbon neutrality. Achieving this has required successive 5‑year plans to combine resources and integrate policies and actions across multiple sectors of the economy, from academia through critical resources to manufacturing and consumer demand.

Crucially China has invested in raw material supply chains, including mining, logistics and manufacturing capacity to the extent that the country controls 50–80% of almost all relevant raw materials, ranging from copper and lithium to esoteric rare earth metals. Its lead is particularly noteworthy in production of intermediate and finished materials particularly where the underlying processes are environmentally challenging, e.g. China has over fifty copper smelters compared to two in the US.

Western Governments have now realised the risks associated with this reliance on China for equipment and materials, and all have policies and ‘Critical Minerals’ strategies aimed at redressing the balance. But China probably has a 10-to-15-year lead. Multinational mining companies do not have the scale of global positions enjoyed by their energy sector equivalents, adding to the difficulty of developing more diversified supply chains.

To access the materials needed, Western leaders need to embrace new investment-based relationships in the global south, in Africa and Latin America in particular. And they will need to consider the permitting of processing facilities, re-establishing sustainable manufacturing capabilities against current environmental and societal opposition.

So, what might be the impact of the new US administration? The incoming President previously withdrew the US from the Paris agreements and has used the slogan ‘Drill baby drill’ as a proxy for his energy policy. Trade tariffs and the overall policy on China are the other key policy areas to watch, and in addition which Biden legacies are reversed, in particular the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

Taking energy first. Post the shale oil revolution, the US is now the world’s largest producer of both oil and gas, and the country is a net exporter of energy. Deepwater investment is increasing again. However, both shale and deepwater have natural decline rates in the range of 15–25% pa and require material ongoing investment to maintain let alone grow production. In addition, investments in the Middle East, Brazil and Guyana and demand growth softening in China and elsewhere have led to oil prices falling to around $70/bbl. Given shale developments are estimated to have destroyed over $700 billion of shareholder value since inception, operators will be cautious.

Hence with much shale oil now owned by the more disciplined majors and with offshore rig rates back towards historic highs, basic economics will perhaps play a more significant role than opening new areas for drilling, potentially reducing production. Companies may be unwilling to enter new areas given non shale development cycles are measured in decades and policies could change again.

It is possible that the main impact on global energy markets may be incentives to consume shale sourced gas in the US, reducing the amount available for export as LNG and to Europe. Given this has been the main mitigant to loss of Russian pipeline gas supply due to events in Ukraine, this could impact EU energy prices as importers would need to compete with Asian consumers for security of supply.

The biggest challenge for the Energy Transition may be Trade policy and within that, how the US chooses to trade vital materials and equipment including wind turbines, solar panels, batteries, electric vehicles, copper, lithium and the microchips essential to intelligence embedded in all these systems.

Significant tariffs on Chinese imports would for some time make US producers highly uncompetitive, at a minimum increasing cost for consumers. Where supply options are constrained, some industries or sectors could become unviable. Existing fossil fuel alternatives may close the power and mobility gaps temporarily, although higher US demand and lower US exports would eventually increase domestic and global energy prices.

Tariffs however may turn out to be more complex and less impactful than feared. The apparent zero-sum view on trade ignores the benefits it brings, on the cost of many consumer products. The impact of retaliatory actions should also not be underestimated. It remains to be seen whether the President elect sees trade as a bad thing per se, or tariffs as a negotiating tactic in pursuit of specific bilateral aims.

An initial intent to increase tariffs on close neighbours and allies Mexico and Canada by 25% was accompanied by demands to control drugs and immigration.

Elsewhere it could be used to negotiate shared security burdens. The 2016 Administration had more rhetoric than effective outcomes.

In addition, several new Administration nominees are clearly pro trade including the Treasury Secretary and Elon Musk. The powerful US business lobby will be clear about the impact of general tariffs on inflation and interest rates, including those regarding China. The worst hit economically are likely to be both elements of Republican support, wealthier business leaders and those who feel dispossessed and excluded from society. Hence it will be key to track the outcomes of the early skirmishes, to project the likely outcomes elsewhere.

The IRA should be considered along with the Critical Minerals Security Act, currently passing through Congress. The latter in effect targets self-sufficiency in important materials including ‘the electric eighteen’ that are vital for the energy transition. The US Departments of Energy and Defense have already allocated significant funds to clean energy and critical minerals projects, many of which are in Republican states. These include mining and processing activities, some of which are already facing public or regulatory opposition. Given US approval and permitting cycles can easily exceed four years, the response of the new Administration to enabling these projects will be a clear indicator of future viability and competitiveness of US based supply and value chains.

If the US withdraws again from the Paris Agreements and imposes tariffs on Chinese components of the energy transition supply chain, progress on the climate will inevitably slow for a period. But the rest of the world is likely to press ahead, and the US will find it more difficult to compete. However, private sector US investment in clean energy technologies is likely in any case to continue, and with access to innovation and financing and ultimately domestic and global markets will become increasingly competitive. The scale of the business opportunity is just too large to ignore despite the head start that China currently enjoys.

Of course, on most of the above challenges, Europe faces the same issues in terms of defending its own industries while still pursuing the energy transition. It is impossible to define the probable outcomes of this multidimensional poker game over the next few years, other than to note that for now, China holds many of the high value cards.

In the longer term though, the direction of travel seems clear. Fossil fuels are a finite and increasingly expensive resource, particularly if emissions are priced appropriately. A clean environment is desirable for all, as are more stable weather patterns. The Energy Transition is ongoing, and despite the many challenges highlighted here, even the new US Administration is likely only to be a bump on the decades-long journey.

Technology, societal mores and ultimately hard economics will drive the outcomes. And change will only happen at the required pace and scale if governments, business and society at large align soon on both intent and execution.

Simon Henry is Chief Financial Officer and Executive Director of Shell.