Winter 2012

Pay and Go: Africa's Money Mobile Revolution

I farm in a remote district of Kenya. The nearest bank is 80 kilometres away and until three years ago, few of the workers had opened accounts. For this reason we used to pay monthly staff wages in cash, the money arriving in blocks of dirty bank notes on a propeller plane at a nearby airstrip. From there we drove the payroll back to the farm. After it was distributed, men would often send their salaries home, and this involved a fresh odyssey of more travel using friends who might journey for hours or even days to get it to families.

One day when the farm car was carrying the payroll, a gang of thugs with semi-automatic rifles opened fire on it. Our vehicle skidded off the track. Luckily nobody was killed in the gunfire. My manager Celestina Sikuku was pulled out and then thoroughly beaten, while the quick-witted farm clerk grabbed the cash and raced off to hide in the bush.

Celestina later recalled how one of the gunmen had pointed a rifle at his chest and pulled the trigger – when instead of BANG he heard a dull click of the gun misfiring.

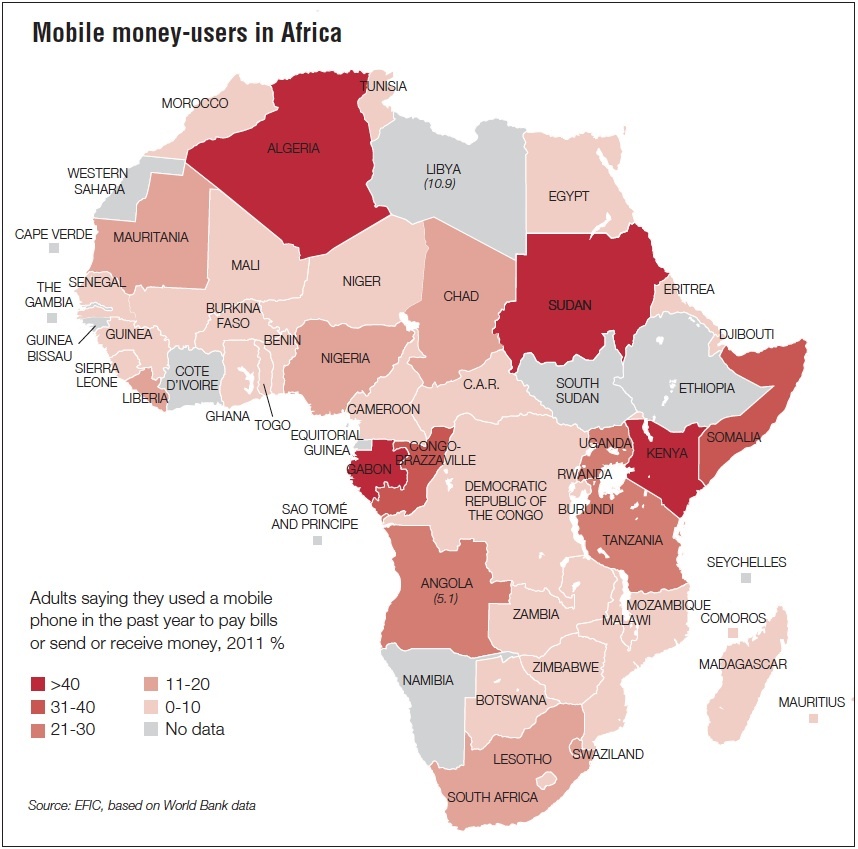

Source: Source: EFIC, based on World Bank data

Eventually, the thieves gave up and fled without the loot.

Since that day we never dared bring cash onto the property. The company now uses MPESA, a mobile money service offered by Kenya’s Safaricom network. Anybody who has a job with us is obliged to open an account with our local Equity Bank’s MKESHO service – which is run in partnership with Safaricom and managed entirely from one’s cell phone.

Today the entire monthly payroll is transacted over MPESA by phone. Butchers used to be too scared to venture out to us for fear of being ambushed by bandits along the way. Now they just send the money to me immediately after we weigh steers on the farm scales. Via MPESA we settle all our suppliers and utility bills – and through my phone I can purchase just about anything I need to — even a plane ticket on Kenya Airways.

That’s just my own mobile phone story about how life became easier in Kenya thanks to our mobile phones – and ultimately run business more efficiently — but the stories are legion.

According to development guru Jeffrey Sachs, ‘The mobile phone is the single most transformational tool for development in Africa’.

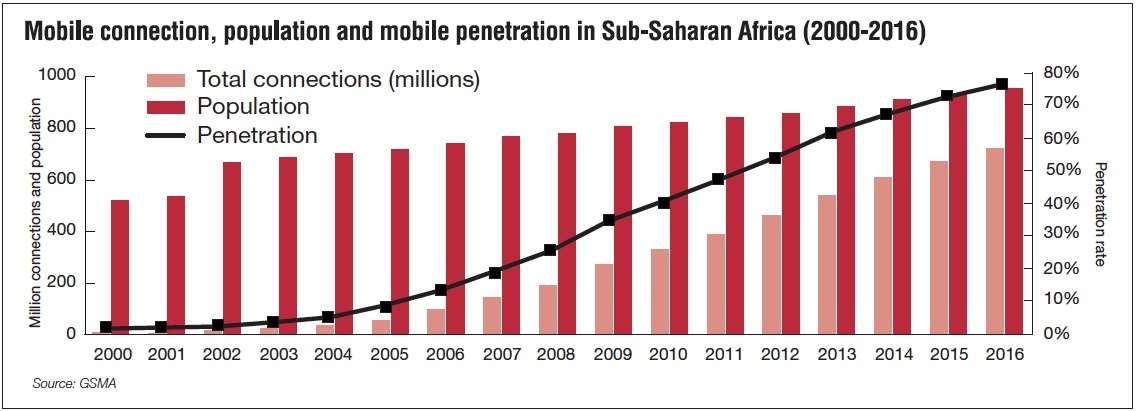

In the West the mobile markets are completely saturated, with subscriptions of well over 100% — but less than half of all Africans even have access to phones of any kind. Even a 10% increase in mobile penetration helps an economy grow by between 0.6 and 1.2%, according to the World Bank and other studies.

Incredibly, when Sudanese businessman Mo Ibrahim bought Celtel in 2000, he said that ‘nobody really wanted to invest in Africa in general – mobile telecoms in particular…’

And yet telecommunications have always led the way in Africa’s development, even if the logic of investment in this area seemed unclear at the time. Ericsson installed the first telegraph poles along the Mombasa-Uganda railway – known as the Lunatic Express because it was regarded as an insanely expensive and purposeless project when it was constructed in the 1890s. Ericsson also installed the Johannesburg telephone exchange in 1912.

Early this year I drove 3,000 kilometres through South Sudan, the world’s newest country since it gained independence from Khartoum in 2011, after a conflict that lasted on and off for more than four decades.

We passed through vast areas that lacked even basic infrastructure such as electricity, schools or health clinics.

Source: GSMA

The murram track was so poor that I imagined our vehicle disappearing entirely into the huge water-filled potholes. But on that journey I noticed one very striking thing: Ericsson was installing 4G technology in mobile phone towers springing up along the entire route through Western Equatoria, a state that even today is occasionally plagued by attacks by Joseph Kony’s ultra-violent Lord’s Resistance Army militia.

At the time not even Great Britain had 4G technology, which was only switched on in the UK later in 2012. On that road trip through some of the remotest country left in the world, I tried to imagine what the impact would be on the local South Sudanese.

I thought about the incredible diversity of uses people might discover in their mobile phones, which now cost as little as $15 – and which even if they are too poor to buy one at this cost can be shared among villagers as ‘community phones’.

They might use their phones to circulate market prices so they can obtain better deals for the food commodities they harvest; health workers might use them as a ‘cell-scope’ to send a picture of a blood slide for analysis, to swipe a barcode on a packet of medicine to check if it is a counterfeit drug, or to connect with teachers in a distance ‘e‑learning’ programme.

Of course they might use their phones for mobile banking, to listen to the radio, access the internet, or even watch television. Across Africa, 99% of internet access is via mobile phones, which are also used more than anywhere else in the world to listen to radio.

These are services that not only generate revenue and improve business in a community – but in a completely new country like South Sudan, they can help bind together people who have lived in conflict for generations and create a sense of nationhood.

Aidan Hartley is a Kenya-born journalist. He writes the "Wild Life" column for The Spectator, and is a correspondent for the Channel 4 award-winning current affairs series Unreported World.