Winter 2021

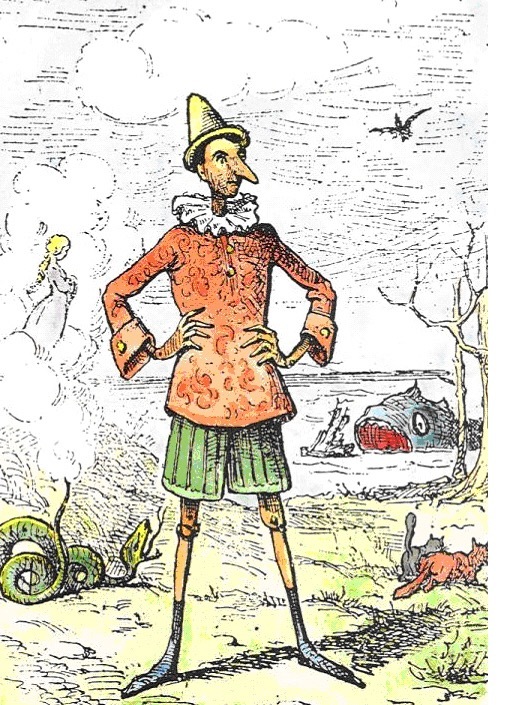

Pinocchio: A Fable For our Times

Source: Wikipedia Commons

Looking for a place in between in Italy, you might well plump for Florence—halfway between the administrative capital, Rome, and the financial capital, Milan. Once in Florence, you might choose to visit the suburb of Castello, halfway between Florence and the next town of any size, Sesto Fiorentino.

Few Italians, let alone foreigners, have ever heard of Castello. If either catch a glimpse of the place, it is from a coach or taxi speeding to the city from the nearby airport. What you see from the main road are warehouses, buildings thrown up in the 1960s and 70s, and a smattering of 19th century houses in a range of slightly drab colours from dark cream to light ochre. What you do not see is that nearby stand some of the grandest buildings in the whole of Florence. This is the area in which the king of Italy had his residence during the brief period in which Florence was the capital after reunification and before Rome was wrested from the papacy.

It has a subtle message for today’s world: if you don’t inform yourself you will remain a puppet forever.

Castello is also one of the few places where you can walk in the footsteps of a literary genius and see the tangible evidence of his creative processes. The genius was Carlo Lorenzini, who wrote under the pen name of Carlo Collodi. And it was in Castello that Collodi drew on real places and people to craft The Adventures of Pinocchio, which—excluding religious texts like the Bible—has become one of the two most widely translated books in the world.

His story too inhabits a place midway between fantasy and reality. It is not just that Collodi drew on real settings and people for his inspiration, but—as we note in the introduction to our new, annotated translation of the

Adventures—it is a highly unusual fairy tale, reflecting its author’s other literary existence as a satirical journalist and social commentator. There are the fantastical trappings of a fairy tale: a dog in livery who drives a coach drawn by mice, a green-haired, green-skinned ogre, not to mention a puppet who can talk and think.

Yet the Adventures is a fable without princes or princesses. It is one that has no valiant knights or vulnerable damsels. Instead, Collodi’s story unfolds in a vividly realistic context: that of grinding, late 19th century poverty. It is riven with hunger and deprivation.

The coming year will see an explosion of renewed interest in Collodi’s story. A live-action remake of the Disney classic 1940 version is due out in the autumn, starring Tom Hanks as Pinocchio’s creator, Geppetto. Shortly afterwards, Netflix is scheduled to release an animated cartoon directed by Guillermo del Toro, who made the Oscar-winning movie, The Shape of Water.

The two films are likely to be very different. Disney spotted in Pinocchio’s extending nose a visually arresting novelty and made it central to his movie in a way that it is not in Collodi’s book. In fact, if the story had finished where its author intended, Pinocchio’s nose would never have grown when he told a lie

The Adventures of Pinocchio sprang from a serialised narrative in Il Giornale per i Bambini (The Children’s Newspaper), published between 1881 and 1883. At the end of the original run of instalments, Collodi left his puppet hanging from a tree, apparently dead. By then, although Pinocchio’s nose had grown, it had never done so when he told a lie. So, if there had not been an outcry from Collodi’s young readers, demanding the tale be continued, we would have no Pinocchio emoji for a fib and no Pinocchios awarded by the fact-checkers at the Washington Post to politicians and other truth-twisters.

Even in the second run of instalments, the puppet’s nose grows on just two occasions in response to his lying. What is more, Pinocchio tells at least three other lies in the second part of the story without anything happening to his nose.

What little is known about del Toro’s film, which is set in the days of Italy’s Fascist dictatorship, suggests that, unlike Disney, he has decided to focus on the import of the original. In the book that grew from the serialisation, the key transformation is not the extension of Pinocchio’s nose. There are two others that are far more significant: one is Pinocchio’s transformation from a puppet into a donkey; the other is his transformation from a puppet into a flesh-and-blood, human child right at the end of the book.

In Italian, the word for donkey is applied both to those who don’t do well at school—and not necessarily because they are stupid, but because they refuse to study. The donkeyfication of Pinocchio and his pal Lucignolo, or Lampwick, gives substance to the notion that is at the heart of the story: the entire plot revolves around Pinocchio either going to school, or not going to school, which is when he gets into all sorts of trouble. Pinocchio narrowly escapes being slaughtered for his hide. But Lucignolo is bought by a farmer who works him to death. Collodi’s message to the children of his time was: being a ‘donkey’ at school leads to working like a donkey afterwards and that the only way to avoid living the life, and maybe dying the death, of a donkey is to study.

But there is also a subtler message that is more relevant—indeed, pressingly relevant—to today’s world. It is first hinted at by one of Collodi’s memorable animal characters, the Talking Cricket. He tells Pinocchio, if he doesn’t go to school, “everyone will make a fool out of you”. Which is exactly what happens: the puppet falls in with two dastardly characters, the Cat and the Fox, who trick him out of his money. What Collodi is also saying is that, if you don’t study, if you don’t learn, if you don’t inform yourself and become an aware and responsible citizen, you will remain a puppet forever. Someone else will always be pulling your strings. It is only after Pinocchio applies himself to his studies and starts to care for those around him that he is finally granted his humanity.

And what more pertinent message than that could there possibly be in an age of populist chicanery?

John Hooper is the Italian and Vatican correspondent for The Economist. Anna Kraczyna, a native of Florence, is a lecturer at CAPA. Their new translation of Collodi’s The Adventures of Pinocchio is published by Penguin Classics