Winter 2018

The Middle East After Khashoggi

The murder of a journalist in Istanbul, while regrettable, rarely causes such aftershocks. But Jamal Khashoggi – whose uncle Adnan once passed on his yacht, the Nabila, to a brash businessman called Donald Trump – was no ordinary journalist.

He was a member of the Saudi elite with powerful friends in Washington and in the cabinet of Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Jamal’s gruesome demise has taken the shine off the Saudi Crown Prince, Muhammad bin Salman, or MBS, whose prints were all over the killing, and who is now being forced under western pressure to restrain his killing machine in Yemen.

This slight but perceptible rebalancing of forces is the handiwork of Erdogan, who regards MBS as an ideological and strategic rival – Turkey’s sympathies lie with the Muslim Brotherhood, foes of the House of Saud– and who, with the chill serenity of a connoisseur, dripped details of the murder into the public domain. The a air has brought prestige to Erdogan as he tries to negotiate his way through a slowing economy, looming corporate bankruptcies and a constricting coalition with the hard right.

And it has weakened MBS and his reform project, frightening off many of the foreign investors who are vital to weaning the country off its oil dependency.

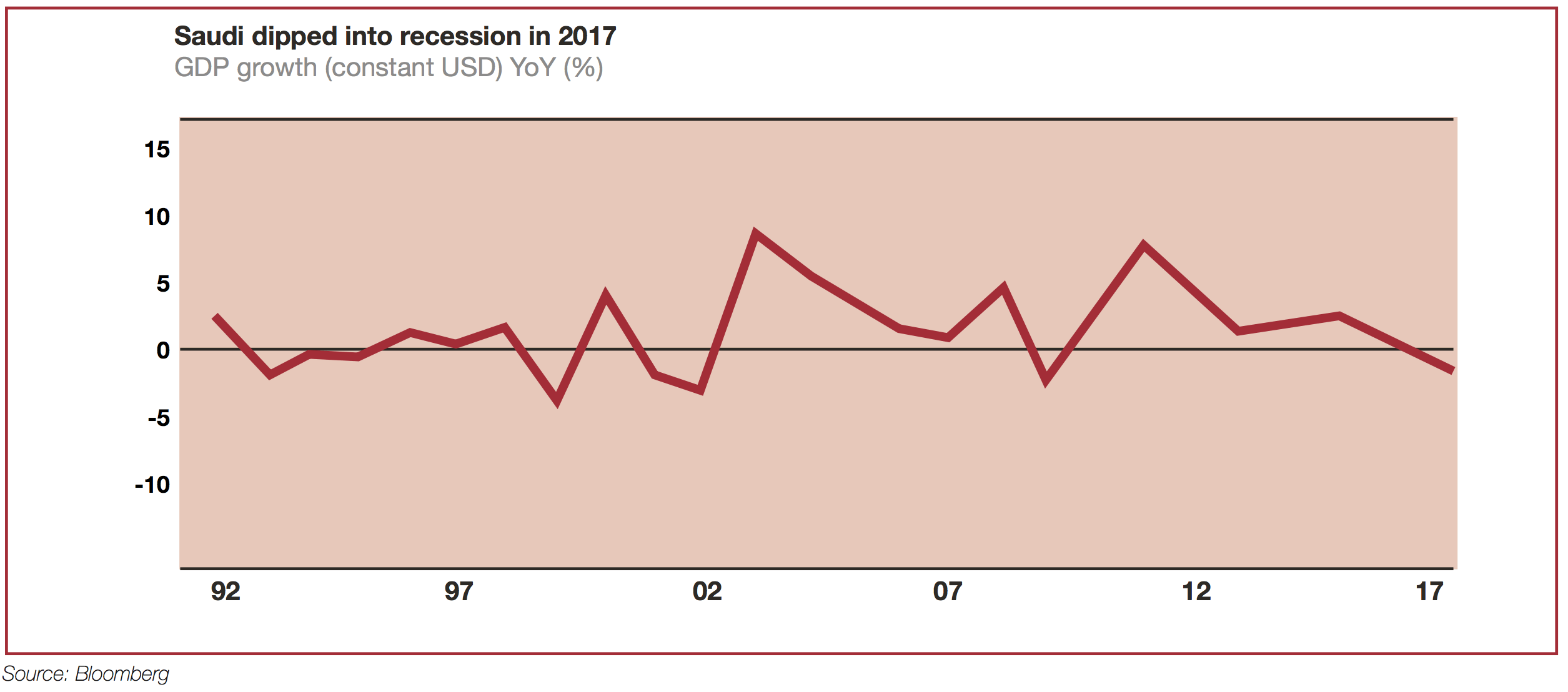

Source: Bloomberg

Perhaps the most important medium-term effect of l‘affaire Khashoggi, however, concerns Iran. Trump is relying on MBS to be his accomplice – along with junior partners Israel and the United Arab Emirates – in making life so unpleasant for ordinary Iranians that they rise against their rulers. With US sanctions now imposed on more than a dozen Saudi officials in connection with the Khashoggi killing, and the possibility that Congress will try and curb future arms sales to the Kingdom, the effectiveness of that alliance is open to question.

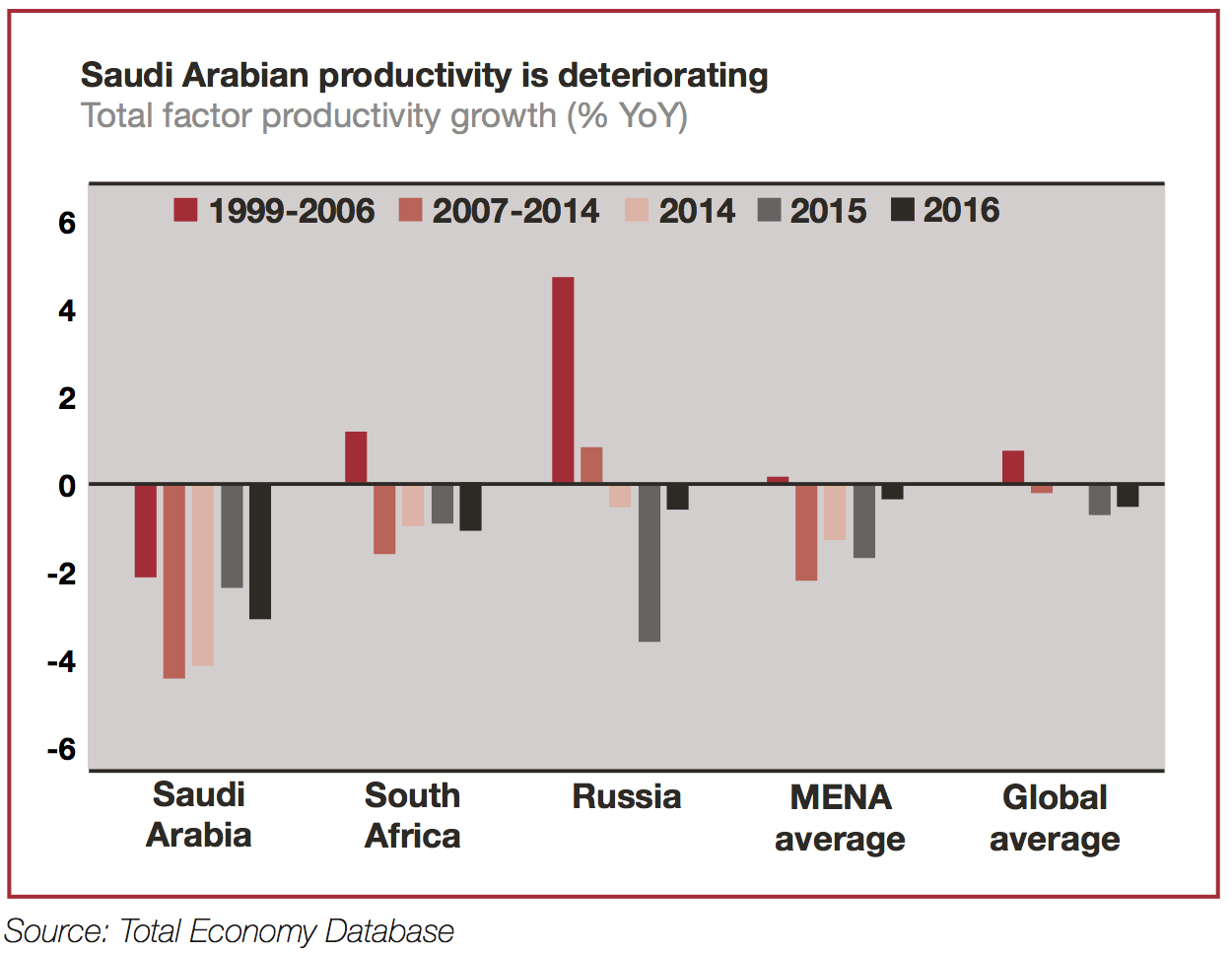

Source: Total Economy Database

And yet Iranian régime change is all President Trump has in the way of a Middle East policy. It started in the spring, when he promoted committed Iran-slayers John Bolton and Mike Pompeo to be his National Security Adviser and Secretary of State respectively. Then the US withdrew from the nuclear deal that had been in force since 2015; sanctions snapped back in November. European multinationals have now fled Iran in order to protect their American exposures.

Belying the Iranians’ insistence that the deal remains in force and that they enjoy the support of the EU, China and Russia, the Islamic Republic is now vulnerable to a pitiless campaign of economic sabotage, covert action and hostile propaganda. But Iran is a dab hand at absorbing pressure and circumventing sanctions; although oil exports have fallen around 1.8 million barrels per day, 800,000 off the peak earlier this year, and protests have rippled across the country, sales will have to fall further before the government is unable to pay salaries. Iran’s allies in Iraq, Yemen, Syria and Afghanistan have a proven track record of disrupting US interests. And the country has a wildcard in the form of its enrichment sites, which are currently silent. If the mullahs fall, a lot could fall with them, while the assumption of the Trumpists that the ayatollahs’ replacement would be an American client complacently ignores the nationalism that courses through the veins of so many Iranians, and their hatred of meddlesome outsiders.

Whether it’s the succession plans of Ayatollah Khamenei and King Salman, who are both old and frail, or the evident determination of President Erdogan to become his country’s leader for life, discussion of the Middle East tends to revolve around family trees, cod psychology and oncologists. The end-game in Syria and the spoils of reconstruction; the chances of either peace and food or more war and famine in Yemen; these appear dependent on a small number of individuals radiating out from the region to include Trump and Putin. In reality, behind the inflated personalities the region is being reshaped, the contracts that define relationships between citizen and ruler being rendered obsolete by youth, aspiration, climatic disaster, smartphones and debt.

All forms of rule, whether in the Middle East or elsewhere, rely on popular legitimacy, or at least the feeling that it would be unwise to trade stability for Utopia. For all their differing ideologies, sectarian shadings and ethnic colourations, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Iran all claim to o er their citizens stability. Look at Syria, they say, for the upshot of fitna, or anarchy. But an understandable popular fear of chaos doesn’t amount to meek acceptance of the status quo. The region is a sliding rink of aspiration, unease, conservatism and restlessness. Graduates no longer walk into jobs for life. People are having to work harder to stand still. Water has run out in some areas. And everywhere there is a profound ambivalence towards the old structures of authority.

A recent academic study of the Saudi social contract, that mesh of mutual interests that has bound prince to populace for decades, makes this clear. ‘Things are changing within the government,’ one young engineering graduate tells its author, Mark C. Thomson, ‘but still our connections with the government are not clear. We see so many important issues being affected negatively: housing problems, unemployment, private sector jobs and even government jobs. The problem is that I do not know how to give back to my country so that my country can give back to me. Should I rely on my education? It is not clear. Nowadays, most engineering graduates rely on banks for money. Additionally, his [sic] house and car are rented and his wedding can cost up to [US$50,000]. How I can get this money for a house, furniture and car? And we have not even started discussing the honeymoon.’

Political events can either compound tectonic shifts in society or they can cancel each other out. The calculation of the Trump administration is that the current Iranian story of protest, corruption and a sense of thwarted destiny can be aggravated by unrelenting outside pressure. Back in 2009, when millions of ordinary Iranians protested against a stolen election, their destination was clear: liberal democracy, whose chief advocate was in the White House. But Iranians are aware of the changes that have taken place since then; while their longing to be accepted into the world community remains strong, the very existence of such a community, bound together by common rules and institutions, has been called into question by Barack Obama’s successor as US president. The decisive factor over the next few years may be the staying power of Donald Trump. A second term would probably increase the likelihood of a confrontation with régime, but distrust anyone who predicts with confidence which way the Iranian people will fall.

Christopher De Bellaigue is a journalist and author who has covered the Middle East since 1994. His latest book is The Islamic Enlightenment: The modern struggle between faith and reason.