Winter 2017

The Middle East Cauldron: Boiling Over?

Source: The Jordanian newspaper ‘Ah-Rad’, The US and Iran are dividing the world

About three years ago, after an interval of forgetfulness, a lot of voices began to be raised against the Sykes-Picot agreement, under which a Yorkshire landowner and a French colonial officer (respectively Sir Mark Sykes and Francois-Georges Picot) carved up the Middle East in a secret deal in 1916. Not only Sykes-Picot, but also the Balfour Declaration of 1917, which promised the Jews a national home, and a plethora of other agreements that cumulatively redrew the map of the Middle East after the fall of the Ottoman Empire – they too were roundly condemned. Furthermore, amid the reproaches of modern Arabs and the mea culpas of the West a consensus emerged that these historic efforts to impose a system of nations on the Middle East had been in vain. With the Islamic State rampant, Syria in fragments, and the Kurds of Iraq running their own a airs and seemingly on the verge of independence, the lines in the sand were disappearing from view.

Since then – and with surprising rapidity – the same lines have come back into focus and acquired new credibility. The biggest challenge to the principle of nationhood in the region, the transnational cod- caliphate of the Islamic State, has been obliterated as a military and administrative force. Provoked by an invincibly foolish independence referendum staged in September by the Kurds of northern Iraq, the Baghdad government swept northwards in a punitive offensive that secured the oil-rich region of Kirkuk and may have set back the cause of Kurdish independence by a generation. In neighbouring Syria, Bashar al-Assad once again controls the major cities and he will dictate the terms of the semi-federal system which the Syrian Kurds, at present in possession of large tracts in the north, will press him to adopt. But one wouldn’t bet on the Kurds in the medium term, especially in the light of the pitiless campaign which has been waged by the government of neighbouring Turkey on their brethren north of the border.

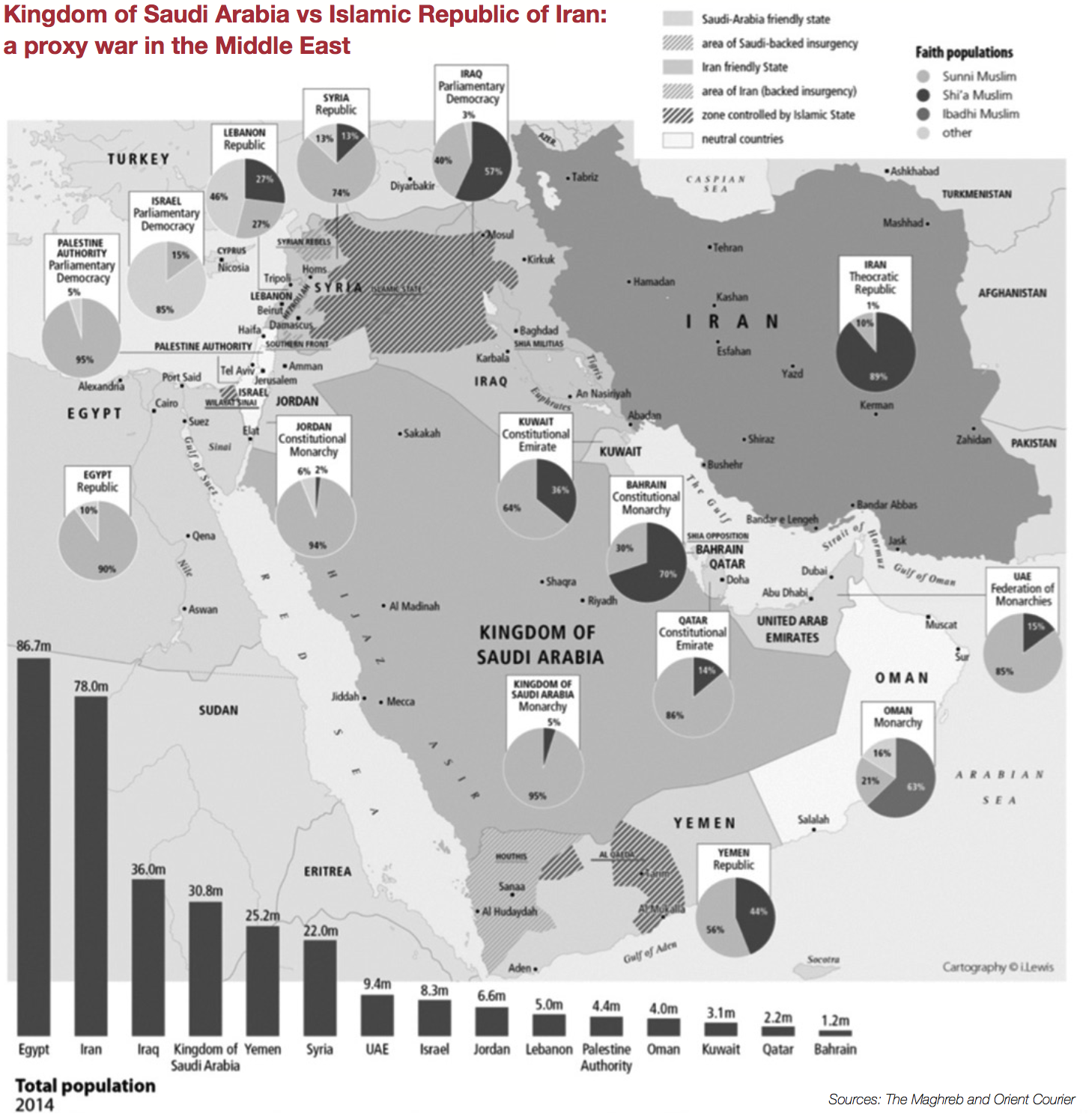

Source: The Maghreb and Orient Courier

For all the arbitrary and amateurish nature of the imperial carve-up of a century ago, and the imperfections of the polities to which it gave birth, it is clear that the nation state will not easily be steamrollered. This is a lesson that Shia Iran – not coincidentally, the most coherent of all Middle Eastern polities – has understood better than its Sunni rival Saudi Arabia.

Iran’s closeness to the triumphant central governments of Syria and Iraq has seen its prestige rise at the expense of the Saudis, closely associated with the fundamentalism espoused by Islamic State. Another lesson about the durability of Middle Eastern nationhood emerged from Saudi Arabia’s recent intervention in the politics of Lebanon – in frustration at Iran’s influence there and in the Yemen imbroglio. That Lebanon’s prime minister, Saad Harari, no friend of Iran or its Hezbollah proxy, was constrained to issue his resignation in Riyadh was read back home as a humiliation. Journalists in Beirut reported an immediate uptick in patriotic feeling; faction-ridden Lebanon is more of a nation than many people had thought.

Toward the end of the Obama presidency, following the deal that froze Iran’s nuclear development in return for sanctions relief, it looked as though America was beginning to favour an old fashioned power balance in the Middle East – as Obama put it in a statement of unprecedented impartiality (for a US president), the Saudis and Iranians should ‘share the neighbourhood and institute some sort of cold peace.’

The election of Donald Trump has killed this idea stone dead, much to the satisfaction of King Salman and his all-powerful son and heir, Muhammad bin Salman, otherwise known as MbS. In Trump and Jared Kushner, the Saudis are now dealing with an administration that nods to their own princely model. MbS speaks directly to the president’s son-in-law, who runs his own Middle East show independent of Rex Tillerson’s State Department. The terms of the unofficial deal with Saudi that passes for American Middle East policy was summed up thus by Philip Gordon, Obama’s former regional point man: ‘Buy more American weapons, announce investments in the US, pledge to fight Islamic extremism, and, in return, we will give you unconditional support–for your confrontation with Iran, war in Yemen, isolation of Qatar, and whatever domestic practices you see fit.’

These ‘domestic practices’ are to include a raft of reforms designed to diversify the economy, emancipate women (beginning by letting them drive), and promote what MbS has called ‘moderate Islam’– prising Wahhabism away from clerics whose teachings have been used to justify jihad, anti-Shia bigotry, and sundry brutalities against insufficiently shrouded females, the country’s Shia minority, and other undesirables. Floating the national oil company, Aramco, on a foreign bourse is also on the cards. It’s an ambitious programme only an absolute ruler could entertain, as was made clear on 4 November, when MbS arrested 11 princes and nearly 200 members of the Saudi business elite–a concentration of power in the hands of the Crown Prince (possibly also pre-empting a coup) that Trump did not hesitate to applaud.

What Gordon did not mention was the other objective of the Trump-Kushner scheme, which is to bring about a rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and Israel and impose peace – on Israeli terms – on the Palestinians. Nowadays Saudi and Israeli officials meet on the sidelines of academic conferences in the US; and Kushner, who has been shuttling between Jerusalem, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, capital of the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia’s main ally, has let it be known that he is preparing to unveil a grand plan for peace underwritten by the Arab monarchies.

In November, the Chief of Staff of the Israeli Defence Force gave an interview with a Saudi news outlet in which he said there was an opportunity for ‘a new international alliance’ between Israel and ‘moderate Arab states…there are many common interests between us and them.’ And what exactly do these unlikely partners – a right wing Israeli government, the Wahhabi monarchy, and Trump’s America –have in common? A visceral, almost pathological hatred of Iran.

The rivalry between Iran and Saudi Arabia is characterised by a basic asymmetry. Although the House of Saud lacks the pedigree for a caliphal claim, it sees its ownership of the holy places as grounds for leadership of the Muslim world. Riyadh regards Iran as an existential threat to Sunnism and many senior Saudis – though not, apparently, MBS – share the IS view of Iran as a nation of apostates.

There is no answering obsession with Saudi Arabia in Iran. Although Iranians in general abhor aberrant o shoots of Wahhabism like the Taliban and the Islamic State, one doesn’t hear officials or senior Shia clerics demonise Sunnis tout court.

The Islamic Republic is acutely conscious that it represents Islam’s minority sect; its actions are designed to mitigate that disadvantage. It cooperates pragmatically with Sunni Turkey and has come to Qatar’s aid in its ongoing dispute with Saudi Arabia, the objective being to prevent the formation of a monolithic, Saudi-led coalition against it.

The Iranians are doing quite well. Not only do the Islamic Republic and its (battle-tested, increasingly well-equipped) Lebanese proxy hold the whip hand in Lebanon; they backed the winners in Syria and have the moral ascendancy in Yemen, where a Saudi-led blockade (intensified after Iran-backed rebels red a ballistic missile towards Riyadh) has brought much death and misery. Iran’s investment of resources in the war has been minimal compared to that of the Saudis and their Emirati allies. Furthermore, the closer Riyadh gets to Israel, the easier it is for Iran to question the Saudis’ Islamic credentials.

The Islamic Republic may be more capable of absorbing external shocks than the Kingdom. The social contract in Iran, where people vote (albeit from a vetted field) and pay taxes (albeit reluctantly) has sustained the country through dark periods. An eight-year war with Iraq, a youth bubble, oil price fluctuations and decades of sanctions and American hostility have been weathered. Iran has been reforming – haltingly, but perceptibly – ever since Khomeini’s death in 1989. A sluggish, unproductive economy with high unemployment – the current situation – is nothing new.

There is no such social contract in Saudi Arabia, where taxation and representation are abstract terms. MBS’s attempts to disestablish the hard-line clerics by ignoring their fatwas and neutering their morals police and his intention to allow Dubai- style entertainments may embolden a reactionary opposition, particularly if he fails in his endeavours to reform the rentier state. At the current burn rate, Saudi Arabia only has a few years to modernise its economy or face a financial crisis. The Iranians know this. As President Hassan Rouhani taunted the Saudis in November: ‘For how long do you think money will keep you out of trouble?’

The game, then, has been proceeding in Iran’s favour. But now there is a wild card in the form of Trump and his desire to destroy the nuclear deal, which led him to decline to certify Iranian compliance in October. (That Iran has been complying with its side of the bargain has been attested by the UN, the EU, and even the US State Department.) The next few months, as Congress and the administration juggle the hot potatoes of exiting the deal and reapplying sanctions, are going to be important. If the US does scotch the deal cool heads in Iran will argue in favour of continuing to honour its provisions, and in this way retain European support. But it would also be an opportunity for Rouhani’s hardline opponents to press for a resumption of nuclear development.

The threat of secondary sanctions being imposed on non-American companies doing business in Iran would reduce what is in any case an underwhelming ow of western investment into the country. More dangerous would be a reprise of the international oil embargo and Iran’s exclusion from the Swift international payments system, a combination that crippled the economy before Rouhani’s election in 2013. Whether Iran’s sang froid would survive new sanctions, or the death of the ageing Ayatollah Khamenei, or the end of Rouhani’s second (and final) term in office, is unclear. Another crisis is being manufactured needlessly in the Middle East.

Christopher De Bellaigue is a journalist and author who has covered the Middle East since 1994. His latest book is The Islamic Enlightenment: The modern struggle between faith and reason.