Covid 19 Edition

Time for a New Social Contract

After two world wars and the great depression, American business faced a daunting challenge. With the wars’ end, millions of servicemen would be returning home, but to an economy transitioning to a peacetime footing from wartime mobilisation. By some estimations, more than 30 million people could end up unemployed, sending the economy right back into the depression it had only recently escaped. Faced with this reality, business leaders took actions that, absent such a looming crisis, they might not have considered. They embraced the concerns of labor. They encouraged deficit spending by the government.

As no less a representative of corporate America than Harrison Jones, the CEO of Coca Cola said, companies would need to start hiring more workers than they needed “so that the nation’s economic flywheel would begin to turn — workers becoming consumers, leading to demand for more products made by more workers.” In addition, prices would need to be low and pay-checks high — even though that would obviously affect profitability.

This set of practices contributed to decades of shared post-war prosperity and the rise of a large middle class in the west. Business leaders joined the Committee for Economic Development, advocating for all these policies and others (such as the Marshall plan) that would shape the post-war economy. Trade began to increase wealth. Relatively high marginal tax rates lessened the incentives among corporate leaders to game their systems to enrich themselves. Layoffs were considered a sign of poor management and irresponsible stewardship. And banking was boring, as the financial sector was tightly reined in.

The period was also one of few financial panics and steady, profitable corporate growth. The dominant theory of business was “stakeholder capitalism” in which corporate leaders balanced the interests of different groups with a stake in an organisation. Employees, communities, civil society and of course executives and shareholders would benefit from the success of the firm overall, and it would fund steady growth through investing their retained earnings.Economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff in their book This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly, found that in the first 35 years or so after the Second World War, there was virtually no financial crisis anywhere in the world.

The End of a “Golden Age”

Dating most dramatically to University of Chicago Economist’s Milton Friedman’s New York Times broadside of September 13, 1970, this model of capitalism came under attack. A businessman who operated with a ‘social conscience,’ Friedman said, was “preaching pure and unadulterated socialism” (his words). CEO’s, he argued, were agents of the owners of firms, meaning the shareholders, and their one and only obligation was to use the resources at their disposal to make as much money for those shareholders as was humanly possible. Social concerns were left to governments and to people’s own personal money.

The theory of “maximising shareholder value” became ideological cover to justify rolling back many of the post-war practices. It was used to justify eliminating restrictions on the financial services sector, setting the stage for the dramatic growth of that sector. It was used to justify compensating CEO’s on the basis of how well their stock holdings did. It was used to justify corporate decisions such as offshoring production, as this would benefit shareholders, whatever the effects on local communities and workers. It was used to justify mass layoffs for the first time, even among companies that were profitable. And it was used to eliminate (in 1982) restrictions on share buybacks, creating an easy mechanism that in one fell swoop could increase share prices (fewer shares mean a higher share price) and simultaneously boost the compensation of executives.

Alarms were sounded about the long-term consequences. We did start to see truly stratospheric CEO pay, and money that could otherwise have gone into innovation or human capital development has gone into what’s been called “predatory value extraction.”

Reimagining Capitalism

Ironically, the very doctrine which promised more to shareholders is starting to show signs of delivering less. Capitalism, Peter Georgescu says, is “committing slow suicide.” Regular financial panics are back (this time combined with a public health, public policy and environmental crisis). The finance sector has become ungovernable. Worker pay is stagnant, despite massive growth in corporate profits. Income inequality is far worse than many imagine. A recent study found that the top 0.1% of taxpayers – roughly 170,000 families out of the US’s 330 million people — control 20% of American wealth. The top 1% control 39% of wealth. The bottom 90%? Only 26% of wealth.

It is safer to invest in financial assets or in assets (such as real estate, stocks and bonds) that already exist, not in the creation of new ones. Executives’ incentives often aren’t aligned with the long term. When incentives are to engage in financial engineering rather than entrepreneurial activity, it is no surprise that we get more of the former and less of the latter. In her new book Reimagining Capitalism in a World on Fire, Rebecca Henderson convincingly argues that capitalism has truly run amok, largely because social costs of producing private profits are not priced into markets appropriately.

Even more depressingly, as William Lazonick has documented in his broadside of a book called Predatory Value Extraction, companies in the US have gone from a “retain and reinvest” system in which retained earnings are invested to create growth, to a “downsize and distribute” system. There are few limits on certain shareholders, such as activist investors and private equity firms, to pull cash out of such firms, limiting the amount available for investment in innovation and to act as buffers in the event of a downturn (such as we are currently experiencing).

All of this, however, may have reached an inflection point — even Larry Fink is expressing concern. Firms are putting their money into buybacks or paying off financially-engineered debt rather than into investments in their people and in innovation (GE and Kraft Heinz come to mind). Innovation requires investment — in research, in people, in communities and the environment. Taken to an extreme, the very practices associated with returning value to shareholders ultimately destroy it. As wealthy entrepreneur Nick Hanauer points out, the current system is bankrupting his potential customer. As he says,

“You want to have a set of economic policies that ensure that businesses pay workers enough so that they are economically secure. And that should be the price of being in business. If you can’t figure out how to do that, go be a ballet dancer or a firefighter. If there are industries which simply cannot operate while paying workers enough to get by without food stamps, they should cease to exist”.

Covid-19 as an accelerant

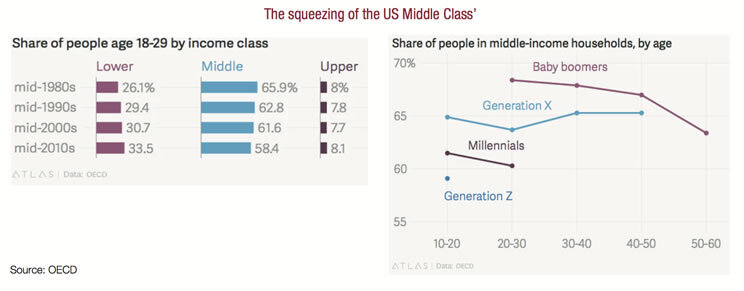

Americans, and to a lesser extent citizens in other developed democracies, have taken notice of their historically reduced circumstances. The Occupy Wall Street movement of 2011 carved the term “the 99%” in the cultural discussion. The middle class has virtually disappeared, with the majority of Americans working jobs with insecure, irregular hours — jobs that were not the good jobs the Committee for Economic Development envisioned, but jobs that could not support families, despite the record profitability of publicly traded corporations. The system, many came to believe, is rigged by people who have wealth and power and can write the rules of capitalism to suit themselves, not using the rules to enforce shared prosperity and effectively use pricing mechanisms to regulate anti-social behaviour.

Source: Source: OECD

The question before us, then, is whether the current crisis can prove to be an inflection point. In many ways, the economic crisis is causing an urgent need to rethink how the system operates, much as it did after World War II. There are already signs that this rethinking is urgent. Organised labor has started to show some signs of becoming more relevant to a population that had been persuaded that its protections and representation weren’t necessary. Workers at high tech company Kickstarter, for instance, voted to form a union, after a long battle with management. Employees are taking a more activist stance at other tech companies as well.

The crisis has accelerated both the scrutiny of, and attention to, the social compact. Front-line workers at companies such as Amazon and Instacart have staged protests at poor pay and unsafe working conditions. The lack of paid sick leave has become an embarrassment for companies in the food service and hospitality industries, with one recent study finding that 12 percent of workers in the food service industry admitted to working while experiencing active bouts of vomiting or diarrhoea.

Some enlightened business leaders offer examples of what such a rethinking might look like. Insurer Aetna, in 2015, raised the wages of its lowest-paid workers and offered benefits that made the company a desirable employer. Xerox, of its own accord, began to create partnerships to make medical supplies in conjunction with unlikely new partners. Despite financial pressure, Bank of America CEO Brian Moynihan put in place a number of firm-wide responses to the crisis, including back-up child care and a no layoff pledge.

We can only hope that the current crisis and the prospect of a potential economic calamity to come might spur a second coming of a collective agreement that continued income inequality and a lack of shared prosperity could be disastrous. We know how to do this.

Professor Rita Mcgrath is an American strategic management scholar and professor of management at the Columbia Business School. Her most recent book is Seeing Around Corners. How to spot inflection points in business before they happen. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019.