Winter 2023

Time Past, Time Present: the UK’s Strategic Resilience Holds, for Now

There are plenty of reasons to be anxious or depressed if you survey the geo-political landscape today. Political extremism, terrorism, mass migration, military adventurism and great power rivalry are all clear to see. Many of these problems are aggravated by climate change. So how well positioned is the UK to cope in this dysfunctional environment?

The UK has a number of traditional strengths in countering, or remaining resilient to, security threats. We have a relatively strong armed forces, good intelligence services, an effective police service, a pretty good history of inter-communal relations and there are benefits in being an island. On the other hand, we are by no means immune to problems.

National security starts with the cohesion of a society. A cohesive community has inherent resilience against shocks. Any survey of the last ten years suggests that our social and political cohesion has come under strain. Political polarisation has increased and extremism has grown, driven in part by the “post truth” world of social media conspiracy theories and holocaust denial, as recounted by Elisabeth Braw. Historically, international events have had surprisingly little impact on inter-communal relations in UK cities. The 9/11 attacks, the invasion of Iraq, even domestic terrorist attacks have rarely had more than a sporadic and very temporary impact. There have been individual cases of victimisation, but at the community level there have been only occasional flare-ups and even these have usually been driven as much by local factors as by international developments.

This historic tendency for the UK to be little affected by communal strife seems to be facing its greatest challenge from recent events in Israel/Palestine. The modern expectation that organisations of all sorts should express a view (or “take a stand”) on matters of public and political controversy, seen very clearly in the Me Too and Black Lives Matter movements, is very hard to meet in the polarised context we currently face. Both pro-Palestinian and pro-Israeli groups feel that they represent innocent victims of persecution, and that their just cause should be given wide and visible support. This raises the stakes higher than in recent memory. Some (though not many) community and religious leaders have started to boycott inter-faith groups as they do not believe that “their side” are getting the support they deserve. Meanwhile we should not underestimate the very real fear that exists in the Jewish community as anti-semitic incidents have rocketed.

So far, the official terrorism threat level has not been raised, which suggests there is no intelligence of actual terrorist planning underway. Nevertheless, there are all the makings of long-term radicalisation in recent events and we should expect that our terrorist problems, which seem to have plateaued in recent years, might re-emerge in the coming months and years. This is what happened in the wake of the Iraq war. Our counter-terrorism arrangements are strong and integrated, but we cannot expect them to shield us from attacks.

In comparison, the UK’s record on managing illegal migration is less reassuring. We have had less uncontrolled immigration than many European states, but more than many British citizens are willing to tolerate. The problem here is not an operational one – being an island makes borders easier to police. The problem is a legal one, where the competing public goods of international human rights agreements, on the one hand, and controlled immigration, on the other, have not been reconciled. We see the battle playing out in the courts and in the media. The government appears to want two incompatible things at once and cannot bear to let go of either. In this it probably echoes public sentiment.

Co-ordinated international action might offer a way forward but we can be pretty sure it will not actually happen as there is neither the will nor the mechanism to deliver it. International aid to developing countries and the resolution of adjacent conflicts might help to remove one of the drivers of illegal migration but on a timescale measured in decades, which won’t work politically. This issue is likely to drive further political disaffection and, to some extent, radicalisation and we don’t have an answer to it.

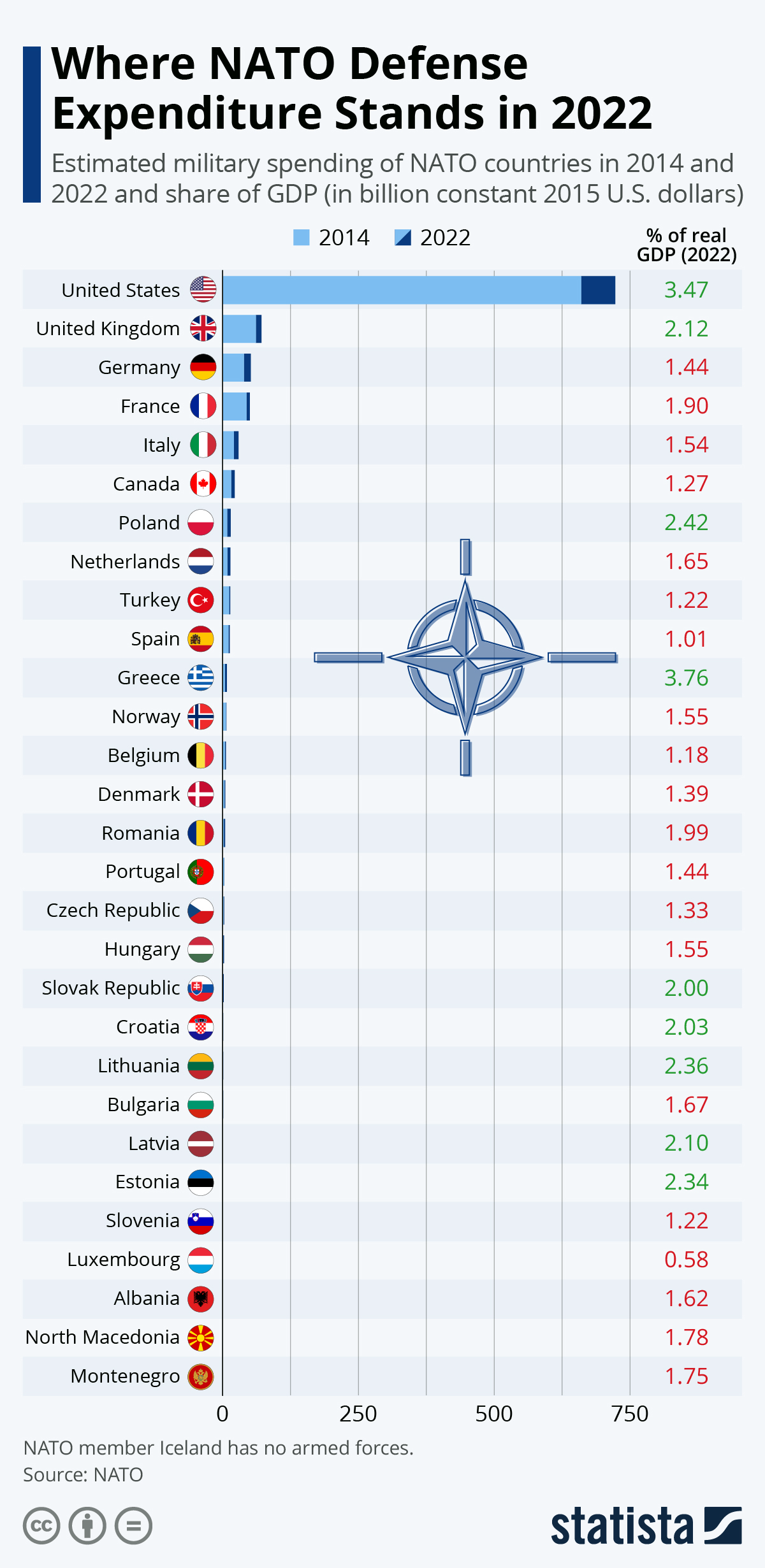

Source: Statista

At a wider geopolitical level our alliances and friendships are vital to our security. NATO has had a purple patch since the invasion of Ukraine, and the EU has done better than expected. But as usual there are clouds on the horizon. International consensus on Ukraine has started to fray and Putin is learning from his earlier mistakes. But the main threat comes from the possible direction of travel of the USA. If there is any substance to the prediction of John Bolton, one of President Trump’s numerous National Security Advisers, that a second Trump administration would see US leaving NATO then we are in real trouble.

The UK would immediately be promoted to become the strongest military component in NATO, a role that we are manifestly unfit to play. With a current strength of around 75,000 and falling, the British Army might punch above its weight but its weight is well below the class, and we cannot possibly substitute for the US. Bolton’s prediction might not come to pass, and there are degrees of “leaving NATO”, but that it is even on the table is alarming. Either way we need to invest in our military capabilities, as do our European allies, otherwise US exasperation with perceived European freeloading will intensify.

We do not need to worry just about our allies, but also about our adversaries. Foreign interference and cyber-attacks have risen in the ranking of national security threats in recent years. Our intelligence defences have pivoted to face them, but adversaries such as Russia and China, sometimes working alongside organised criminals, have strong capabilities combining both state and non-state actors. The UK is probably better prepared for these threats than many of our peers. We are particularly good at cyber, both defence and attack. But we are not configured to respond adequately to the breadth of “grey zone” threats we face, and need better mechanisms to align intelligence defences with other parts of government and those beyond government where the private sector and the media have roles to play. This is a big challenge to an open society.

Addressing these various problems requires several things to happen. First, we need clear and competent political leadership with a strategic intent. The instability, lack of seriousness and ethical shortcomings of some recent governments have failed to provide this sort of leadership in recent years. Trust in government has declined, according to the polling, and there is a feeling that “nothing works any more”. Second, we need adequate resources directed to the strategic ends, at a time when public finances are extremely stretched, the economy is in the doldrums and public debt levels very high. The government has limited room for manœuvre. Third, we need a competent government machine to co-ordinate and deliver all this. An international research project in 2019 suggested that the UK had the best Civil Service in the world. Whether or not that was accurate in 2019, the last few years have not been good for the Civil Service. Relations with government have been punishing, leadership lacking, the merry-go-round of ministerial appointments destabilising and morale has been slipping. It is an open question whether the Civil Service has the technical and managerial skills needed to navigate the problems we face, though many commentators doubt it.

My conclusion would be that the UK is as exposed to many of the current threats as most other countries, and some of our traditional security strengths are under pressure. The position is not by any means irretrievable but, if it is to be retrieved, then we must face up to the problems, decide to act, and take the necessary steps in a resolute and strategic manner.

The writer is a former Director-General of the Security Service, MI5, and is currently Chair of the Committee on Standards in Public Life.