Summer 2012

When Risking Everything Meant Losing All: Who Was the Marquis of Montrose?

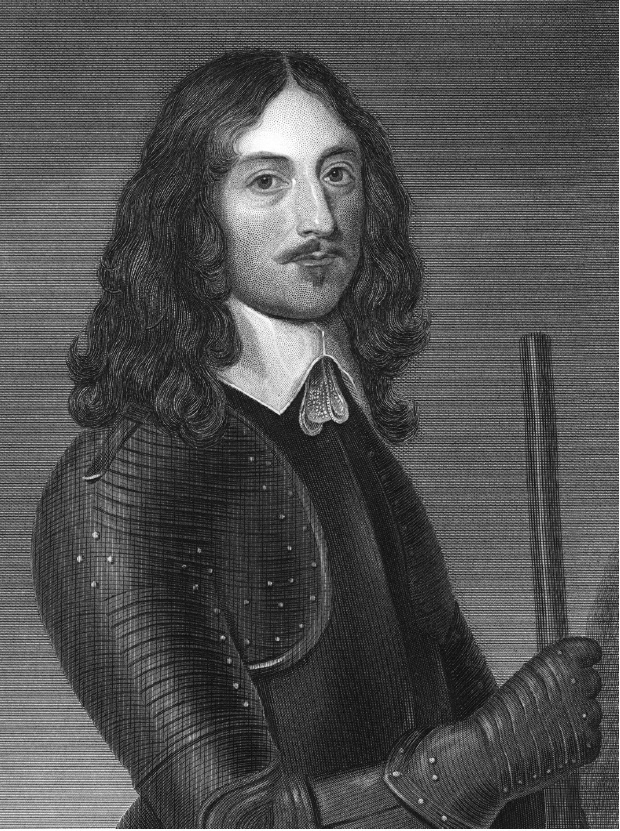

James Graham, First Marquis of Montrose, was a good man born into very bad times. The early seventeenth century in Scotland was a period of economic dislocation, religious conflict and political turmoil. Remarkably, Montrose managed amid swirling tides of brutality, extremism and fanaticism to embody a consistent set of values – of integrity, idealism, and political and religious moderation. And these were his long-term legacy and achievement.

It helped Montrose’s standing that he possessed enormous charm and eloquence, and hailed from one of the noblest families in the Kingdom – and that he was touched with military genius. He was also an accomplished poet and a subtle political thinker. But his enemies were plentiful, and even his allies unreliable and devious. This was especially true of the Stuart King, Charles I, to whom he gave his ultimate allegiance, for whom he died, and with whom history identifies him. But by remaining true to himself, and staking all he held dear on doing what he was sure was the right thing, he still speaks to us across the centuries — on what is this year the four hundredth anniversary of his birth. Montrose first came to prominence as a signatory of the National Covenant which most of the Scottish nobles signed in Edinburgh in 1638. This was a determined attempt to assert Scotland’s religious independence against a clumsy campaign by the Stuart King to impose a Catholic Order of Service in a country that, like much of Northern Europe, was moving toward a more Protestant order of society. Montrose’s fellow Covenanters, as they were called, asked him to take command of the army they sent to Aberdeen in June 1639 to win back this major town from Royalist forces. It was to be the first battle of the Civil War which then engulfed not only Scotland, but England and Ireland, for the next ten years. The irony was that Montrose saw himself as the loyal subject of a King who had taken the wrong advice and was pursuing a misguided policy. Two hundred and fifty years before the French Revolution, he was a man who believed Kings could err, and must in that case be resisted, through armed rebellion if necessary. But Montrose did not think, like the more extreme Covenanters in Scotland and the hard-line Puritans in England, that the King should be replaced by a religious theocracy. During the periods of intrigue and manoeuvring that followed his triumph in Aberdeen, Montrose decided the greatest danger to the Scotland he loved lay not in the inconsistent and erratic Charles Stuart. It lay rather with the ideologues and extremists around Archibald Campbell, Marquis of Argyll – a ruthless and determined faction with a mix of agendas, some of them personal, some to do with the Campbell clan interests in the West of Scotland, and some of them arising from the wave of protestant fundamentalism sweeping across Britain at the time.Like many of the Scottish nobility, Montrose could have retreated to his estates and waited for the storms to blow over.

But that was not his temperament. He was one to stand up for his beliefs, and when he threw in his lot with the King against Puritan republicanism, and against many of his former political allies, he knew he was exposing himself and his family to extreme danger. Accepting the post of Captain General of the King’s almost non-existent army in Scotland, he went secretly on the road, starting with two companions, and raising the royal standard with a few hundred clansmen who had seen their homes and farms pillaged by Argyll and the Campbells.

Winning a first, convincing victory at Tippermuir against a Covenanter army twice the size of his own forces, he embarked on a campaign of extraordinary daring that established him as one of the great military tacticians and strategists in European history. In the course of what was seen as a year of miracles, his battle honours included a second Battle of Aberdeen, where his charisma brought old enemies as well as new friends behind his banner; the battles of Fyvie and Dundee where he won narrow victories against far superior forces; and the overwhelming victories of Inverlochy, Auldearn and then Kilsyth that opened the gates of Glasgow to him. One aspect of his brilliance was a warm and generous personality that inspired clansmen to follow him, even unarmed — fashioning stones and rocks into weapons to surprise the enemy, guerrilla-style, in mountain passes. Another was knowing how to deploy small numbers of mobile troops at the most fragile point of enemy weakness, fording rivers, traversing the mountains at speed, and reversing the flow of battles that seemed lost. From this period dates his great exhortation ‘to win or lose it all’.Montrose was however by now the toast of Europe, as news of his achievements spread. The French King even offered him a post as Marshall of France in his own army. He was also a man of culture who had spent three of his formative years travelling in Italy, Germany and France, learning the joys of literature and painting alongside the arts of war. The temptation must have been strong to sit out the next phase of the wars in Britain, all the more when there was a dalliance between him and Princess Louise, younger daughter of the Elector of Hanover. But Montrose saw his greater duty as raising an army for Charles II, who had meantime succeeded to the throne following the execution of his father by Oliver Cromwell in 1649. Princess Louise retired on his departure to a nunnery, which she never left. Charles II was as devious as his father Charles I in his dealings with Montrose, encouraging him to return to Scotland to renew the war even as he negotiated with Argyll and the Covenanters when their relations with the English Puritans soured. As Montrose returned to Scotland’s most northerly point at John O’Groats, the magic seemed to be working again as he and his half-brother Harry rallied twelve hundred clansmen. But the Earl of Sutherland and the Northern grandees held back, waiting to see how the wars within England and Scotland turned out. Their hatred of Argyll and the extreme covenanters was matched only by the fear of losing their estates. After initial engagements where Montrose faced well-armed forces once more under the command of Leslie, he took shelter in Arveck Castle, thinking himself among friends, only to be betrayed to the Covenanters in return for a reward of ‘20,000 — plus a bonus of ‘5,000 for meat provisioning. His progress to Edinburgh is again the stuff of legend, his dignity and courage shaming those along the route who sought to mock and provoke him. A Kangaroo Court sentenced him to be hung like a common criminal. Covenanting preachers were sent to torment him on his last night. Even Charles II sent his regrets to the Scottish Parliament that Montrose had returned in his name. Yet in his Tolbooth cell, his spirit was not broken, and Montrose famously scratched into the windowpane one of his finest poems, ending with the words:He fears his fate too much,

Or his deserts are small

That puts it not unto the touch

To win or lose it all.

His words were prescient. Dressed as a cavalier in scarlet, with a white linen shirt, white gloves and red stockings, he went to the scaffold in good heart. One observer said “He stept along the streets with so great state, and there appeared in his countenance so much beauty, majesty and gravity as amazed the beholders”. But after his execution, his head was put on a spike and displayed at the Tolbooth, and his body was dismembered, the limbs being distributed around the major towns of Scotland. Yet that is not the end of the story. In a manner of speaking, he had the last laugh. Eleven years later, his head was replaced on the same spike by that of the Duke of Argyll, as Scotland, like England, recovered from its period of barbarity and madness. The remains of Montrose were brought together and given a solemn burial in the great Cathedral of St Giles, where the words of his last poem are even today displayed in the chapel containing his tomb. Montrose was as visionary in his politics as in his poetry, seeing long before others of his generation that imperfect kings would be best constrained within a framework of consent and moderation, not revolution. It would be wrong to hail him as a democrat before his time, and posterity has always found it difficult to define or pigeonhole him. He cannot be claimed as a great nationalist, or for his religious fervour. It is for his military accomplishments that he has been most acclaimed. But his modern sensibility, his courage and his integrity make him a fascinating figure four hundred years on. Montrose’s risks were daunting and the personal price he paid in taking responsibility for the risks he took was great and painful. But his willingness to fight and die for beliefs that we can understand today can still inspire us across the centuries.Scatter my ashes, strew them in the air.

Lord, since thou knowest where all my atoms are,

I'm hopeful thoul't recover once my dust

And confident thoul't raise me with the just".

Michael Maclay is Executive Chairman of Montrose Associates