Winter 2021

Afghanistan: The West’s Great Failure

“The people of Afghanistan do not deserve this,” tweeted Khaled Hosseini, author of The Kite Runner, from Afghanistan last August.

He was reacting to the US completing their evacuation mission from Kabul airport. It was not so much a case of the nation with the world’s most powerful military cutting and running from one of the world’s poorest and most needy countries, but more like one of running and cutting.

When the US planes took off from the multi-billion-dollar Bagram base a few weeks before, thus ending the end of US credible military presence, the generals, the diplomats, and the president told no one. The lights shut down on a timer twenty minutes after the last fighter zoomed off. Not even the Afghan Army general in charge had been informed by his American colleagues.

The seizure of Kabul and all the main provincial centres by the Taliban in a matter of weeks should have surprised no one. But British generals, among others, surmised that the beleaguered government of President Ashraf Ghani might hold off for weeks or months, and bring matters to an honourable truce.

It was wishful thinking – no doubt to disguise the grim reality and depth of the debacle, whose full impact is still sinking in. Some 5,000 prisoners were released with the quitting of Bagram, and many returned to the fray to accelerate the régime collapse in Kabul.

It was all pretty sudden. On 9 July the Taliban had taken 90 provinces, the government held 141, while 167 were being fought over. By 16 August the government of Ashraf Ghani held nothing, only seven outlying regions, the Panshir valley among them, were still being contested.

Today, at the out-turn of the year 2021, with thousands on the brink of starvation, Afghanistan is in the grip of famine in many areas, with thousands and possibly millions on the brink of starvation. Kabul is nominally under the control of the Haqqani network, the notoriously tough Pakistan-orientated element of the Taliban. The Haqqani also run the ministry of the Interior. Girls above grade six, are turned away from schools, and many women have been stopped from resuming their work in offices.

No international power, not even Pakistan, that did much to plan and facilitate the return of the Taliban to power, has recognised the new régime. This means it is difficult to import much-needed food aid and medical help.

Though collapse had been foretold by many who knew that Joe Biden wanted to quit Afghanistan at all costs as ardently as Donald Trump, it is the shape of the debacle that has caused real upset. If its full implication is considered, it is truly a strategic shock of grand geopolitical proportion. It calls into question the viability of the principal western alliance, Nato, as nothing else since the end of the Cold War. It calls into question the military efficacy and diplomatic credibility and ethics of the United States. Above all, as Joe Biden seemed to forget in his early pronouncements about the end of the US mission, it is a disaster for millions of Afghans and their neighbours.

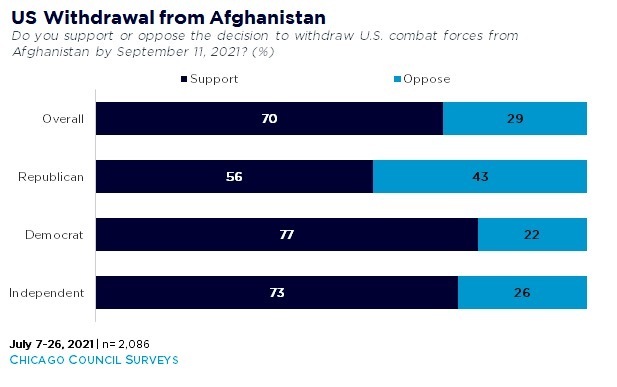

Source: Chicago Council on Global Affairs

Real gains had been made for many Afghans over the past 20 years of international intervention. Millions of girls were going to school – five to six million by the end of last year – where under a million went to class twenty years ago. The big innovation – and this is going to be difficult for the Taliban to manage – is the arrival of IT and computing and the mobile phone. Up to 80% of the country had mobile cover in the past ten years. The phone has brought a new media savviness and literacy for the young that the Taliban elders and commanders will find hard to dial down.

The Taliban will have to deal with the outside world to attract funds.

With this came a new gutsy journalism – by tweet, app, local radio, blogs, news sheets and television stations – some run primarily by women. A lot of this has gone, but quite a proportion has just slid underground.

Some who have dedicated and risked a large part of their working lives to the betterment of Afghanistan are determined to find some cause for hope. General Sir Nick Carter, who is about to retire as Britain’s most senior commander as Chief of the Defence Staff, for one doesn’t believe it is all over. The Taliban will have to deal with the outside world, he says, as they need to talk, trade and attract funds. It is crucial to start the process immediately in order to get food, medicine and housing materials in with dispatch.

Others are less generous and more brutal in their criticism, not least of themselves, and about the failures of Western leadership. Greg Mills and David Kilcullen have been advisers, and commanded in the field for much of the 20 years of the US-led intervention. Their brilliant new essay “The Ledger” assesses the extent and future impact of the failure.

They contend that American presidents and vice presidents with the exception of George W Bush, lacked conviction about the mission to Kabul. They didn’t really believe in it, and it showed. Among the worst were Vice President and then President Joe Biden, and President Barack Obama – their insouciance leading to fatal error.

“Our hope is that we will see a relatively stable government in Afghanistan, one that …provides the foundation for future reconstruction of the country,” stated Senator Biden in 2001. In 2003 he explained, “the alternative to nation-building is chaos, that turns out bloodthirsty warlords, drug traffickers and terrorists.”

On August 16 August 2021 President Biden claimed, “Our mission in Afghanistan was never supposed to have been nation-building”. His vice president, Kamala Harris was more sanguine, stating, “the mission had achieved what it had gone there to do.”

Mills and Kilcullen see the Doha agreement of February last year, between the Trump administration and a Taliban delegation, as the point of departure for this year’s Taliban takeover. It showed a lack of creative diplomacy, and lack of political will and imagination. The talks were between a US team and a team from the Taliban – how representative this was is still an open question. The Kabul government of Ashraf Ghani was not involved, nor were any of America’s allies who had produced men and women, and money, for the project they devised for Afghan stability.

Source: The Economist

Trump had made no bones from his election campaign of 2016 that he wanted out of the ‘Forever Wars’, Afghanistan above all. Biden felt the same and saw no reason to adapt it or re-assess the likely consequences.

The collapse was almost entirely of American’s designing, Mills and Kilcullen argue. The sequence of events was, if anything, more chaotic than the collapse of the American endeavour in Vietnam, right down to the scramble with refugees and evacuees from Saigon in 1975 and Kabul in 2021.

“I am exhausted. I am frustrated. I am angry,” wrote general Sami Sadat in the New York Times of 20 August, 2021, explaining the roots of what he depicts as Afghanistan’s betrayal. Sadat commanded the 215 Maiwand Corps and then the defence of Kabul when it was too late. He quotes Biden, again from August 2021: “American troops cannot and should not be fighting a war and dying in a war that Afghan forces are not willing to fight for themselves.”

General Sadat points out that more than 66,000 Afghan soldiers had been killed in just over ten years. Earlier this summer military and police casualties were reaching 5,000 a month. The debacle had three main causes, suggests the general. The Doha deal was a stitch-up, though he doesn’t use the term – it was a deal between team Trump and a Taliban group that could only end in a Taliban takeover. “It doomed us,” he writes. Next, the 17,000 foreign military contractors and enablers started leaving in January, and were gone by the end of June. So, the US planes and helicopters could not be serviced, and were grounded. Most of the 200 bases were now cut off and could not be resupplied with troops and ammunition. “The Taliban fought with snipers and improvised explosive devices, while we lost aerial and laser-guided weapon capacity.”

The American script has been one foot on the accelerator, the other on the brake

The third cause for implosion was the rampant corruption among Afghanistan’s military, tribal and political elite, coming from the top under Presidents Hamid Karzai and Ashraf Ghani. “That really is our national tragedy,” he writes. But the Americans appear to have bought in to the kickbacks and bribes, despite great misgivings by some US officials such as Ambassador Peter Galbraith, who resigned from the UN mission in Kabul over the rampant corruption in the Karzai presidential re-election campaign. The attitude seemed to be that if it’s a kleptocracy, at least it’s our kleptocracy.

General David Petraeus endorses the critique of Sami Sadat. He told the UK House of Commons Defence Committee in November 2021, that once the US and foreign engineers and maintainers left, the Afghan forces were crippled fatally. He was surprised that anyone thought they could continue to fight effectively. The allies brought unprecedented amounts of cash with them, leading huge amounts of jobbery and theft. US commanders in the field had ‘emergency fund’ allowance of up to $100,000 – beyond a king’s ransom for most in rural Afghanistan.

Mills and Kilcullen see it as the single most undermining factor for good governance. Karzai rode the system, and so did his successor. Ironically in 2008 the academically minded banker Ashraf Ghani with his colleague Clare Lockhart published a book called “Fixing Failed States.” Now he has been fixed by his own failed state.

The American script, almost from the beginning, has been one of one foot on the accelerator, the other on the brake. And the international military effort has been an almost exclusively American enterprise, according to General Sir Nick Parker, who had been deputy commander of the international sustaining force ISAF. “The coalition never really worked as a coalition. It was the Americans with their twin strategies, Afghanistan after the ousting of Al Qaeda, and Operation Enduring Freedom (which was part of Donald Rumsfeld’s Global War on Terror, GWOT). The other governments more or less did their own thing” some as little as possible, it must be added, concentrating on force protection.

The American motif of brake and accelerator was illustrated starkly in the early days of the Obama-Biden administration. In December 2009 Obama chose a ceremony at West Point for the announcement of a surge of US troops to Afghanistan, of 30,000. But at the same time, he announced that the US would start the draw down of the troops from the country in July 2011. “Some of those coming in will pass those going out,” one US officer remarked grimly as together in the ISAF HQ in Kabul we watched the live television broadcast of the Obama speech.

For many allies, Britain, the Netherlands, France, Germany, Denmark and Canada especially, the big reinforcement – and change of mission – came with the expansion of the ISAF forces to cover main provincial bases across a large part of the country in 2005 and 2006. Britain proposed sending 3,600 troops mostly to the drug producing province of Helmand, while the Dutch and Canadians, moved or reinforced in Uruzgan and Kandahar.

How these missions came to be planned and shaped by soldiers and officials in the Netherlands and UK is forensically examined in an extraordinary book by a serving Dutch officer Lt Col Mirjam Grandia Mantas, who completed two tours in Uruzgan. “Inescapable Entrapments? The Civil-Military Decision Paths to Uruzgan and Helmand,” (University of Leiden Press, order on line, in English) is one of this year’s must-read books on the Afghanistan debacle – along with Kilcullen and Mills’ The Ledger – for unvarnished insight into the planning contortions and cockups for the Helmand and Uruzgan missions. So far, I haven’t come across a single UK politician or civil servant involved in Afghanistan who has read it.

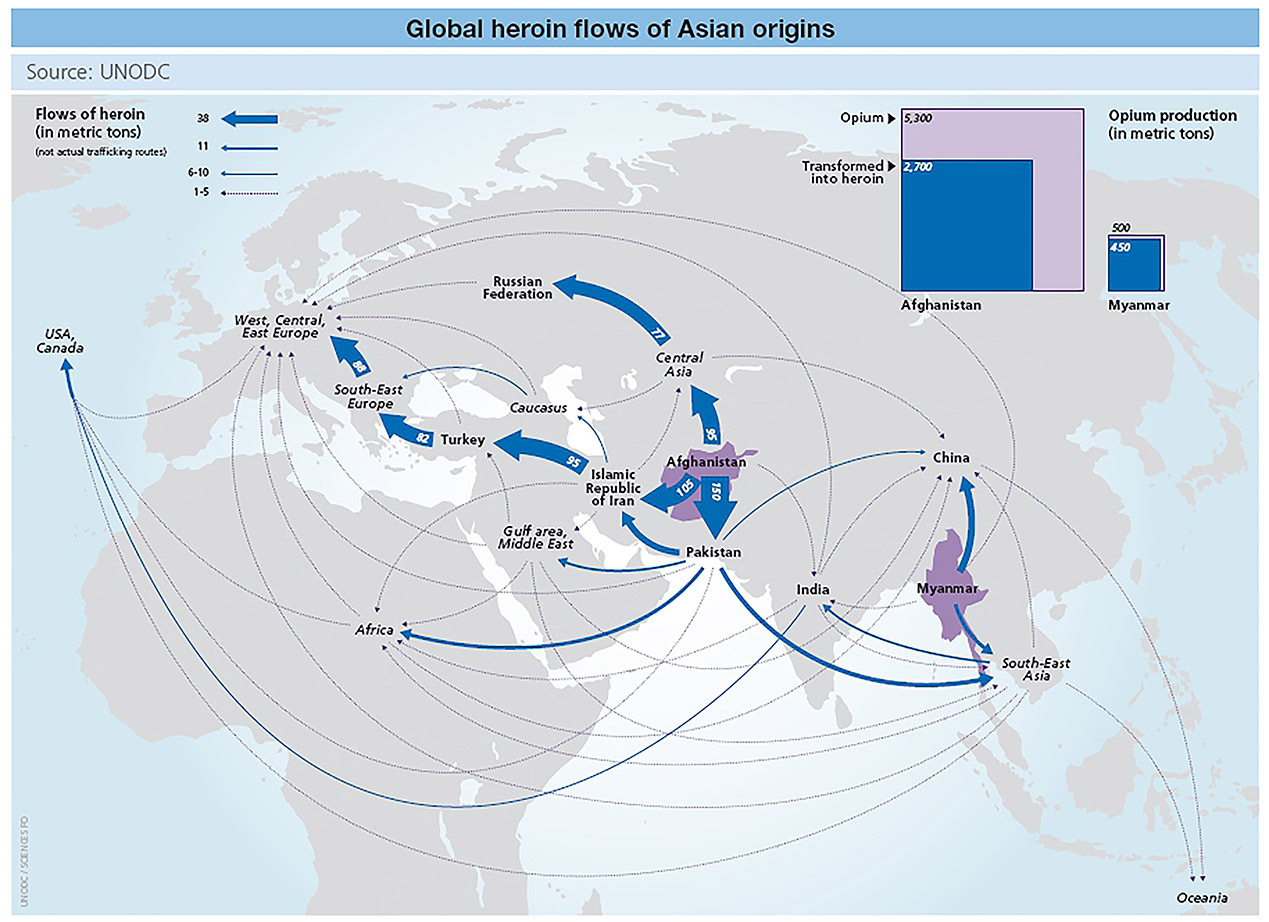

Source: United Nation Office on Drugs and Crime

Grandia Mantas explains that both the Dutch and the British planned their southern foray for motives that had little to do with what was happening on the ground in the two provinces. The British wanted to compensate for setbacks of their operations in Iraq, to show they were a strong ally to the US and knew how to make Nato viable in the field. Likewise, the Dutch, with the shadows of the debacle at Srebrenica in 1995, and their role in the UN in Bosnia, still hanging over them, wanted to show their military credibility, and with that the effectiveness of Nato. “In fact, the military were being asked to do jobs and tasks for which they were not configured or trained,’ she told me recently. Intelligence was received about the narco-economy and the embedding of Taliban in local communities – only to be ignored. British and Dutch planning was professional and detailed but got little critical support from the politicians; the disconnect between soldiers and officials and the politicians is particularly marked in the British case.

The British government and parliament agreed finally to send a force of 3,150 to Helmand for three years for a cost of around £1.35 billion, and the Dutch a force of 1,200 for two years at a budgeted cost of €320 million. By the time the British core fighting force of about 2,000 arrived under the command of 3rd Battalion the Parachute Regiment, they were in the middle of a full-blown insurrection by an alliance of Narco warlords and resident Taliban. “Once a foreign soldier put foot in Helmand, there was bound to be a big fight – they were ready for them,” Anthony Fitzherbert, an agronomist who has known Helmand since the 80s, told me. He also told the UK government. He was ignored.

The anti-narcotics campaign was almost a pet project of Prime Minister Tony Blair. Given the scale of the culture – Helmand then as now being the single largest concentrated area of opium poppy production in the world – his ambition bordered on fantasy.

Inspiration for Grandia Mantas’ research is D Michael Shafer, author of the 1988 ground-breaking study “Dangerous Paradigms.” In it he examines stabilisation operations in the post-war era, Vietnam, the British in Malaya and the similar experiences of other powers such as France and the Netherlands. In particular he parses the notion of ‘protected villages’, emanating from British counter insurgency in Malaya, a focus in Vietnam, and, yes, we even had versions of it in the ‘security and stabilisation’ phase of ISAF in Afghanistan from 2006 to 2014. It finds its way into the revised Counter Insurgency – COIN – doctrines and manuals of the US Army and Marine Corps. It informed the ‘defending the population’ approach of David Petraeus and the nostrum he put forward for ‘courageous restraint’ in avoiding civilian casualties.

One must wonder how much the critique of D Michael Shafer, and later refined by Col Grandia Mantas, was ever considered by British and American military and civilian planners. It might have saved a lot of wasted energy and ammunition, and lives, if it had. Shafer suggests that these measures stand little chance if there is weak, corrupt governance at the centre of the state and régime involved. Corruption was a dominant factor in making Thieu’s Saigon régime and Karzai/Ghani’s in Kabul unviable in the long run.

This is not to diminish the real advances that have been made in girls’ education for instance, technology, improved agriculture and medicine. But governance, and its corruption remains the heart of the problem, General Sir Nick Parker concurs. “You can have the great improvements in literacy and medicine, but it all rests on government and governance and that is what has failed.” Education for girls continues in underground schools and universities – and they deserve all the help they can get. Agricultural techniques improved, and women will not be as disempowered as much as the Taliban and their moral police may wish.

Source: Wikipedia

Women in the professions, especially the judges and lawyers, seem especially vulnerable. As General Nick Carter has written recently, it is very difficult for outsiders to nudge leaders using harsh tribal custom to more tolerant and inclusive ways; and it takes generations to change attitudes. Reporting for some 15 years among women’s cooperatives and workshops, schools, community clinics and all-women radio stations, I found it depressing to discover what they were up against. One Hazara woman tailor told me her husband would kill her if he knew she had even spoken to me. In Khan Nashin in south Helmand, pre-pubescent girls were being forced into marriage with men the age of their grandfathers. Child brides were traded, and girls mutilated to damage their beauty if they didn’t make the right bride price. In one bad case of physical abuse and rape by a husband who was a policeman, he was supported by his tribal elders. Besides President Karzai’s régime had acknowledged a that rape in marriage was not unlawful.

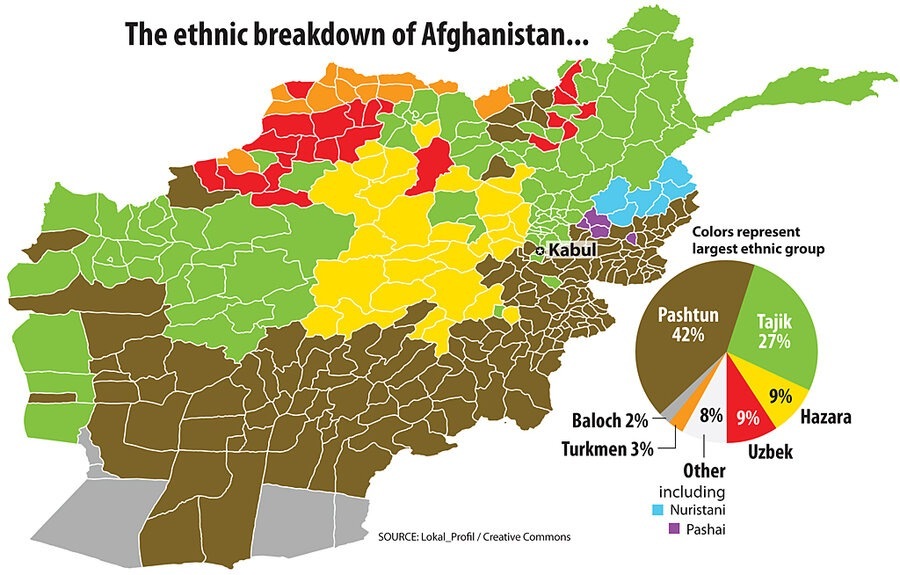

Today Afghanistan is heading into another civil war, an on-off cycle it has been enduring for nearly 50 years now. This time it is the Taliban and the different Pashtun elements turning on themselves, with attacks in several cities from the revived and more vehement ‘accelerationist’ extremists such as IS Khorasan and their allies – a stronger presence now than the Taliban militias back in 1996 when they first came to power in Kabul.

This is complicated by the role of Pakistan in sponsoring the present generation of Taliban fighters and leaders. Mills and Kilcullen, practitioners with years of field experience, state bluntly that the Taliban offensive was planned and encouraged by elements of Pakistan’s military and intelligence agency the ISI. The campaign was sequenced with professional attention to detail and precision. Mills and Kilcullen believe the Pakistan planners must have worked on the attack plan over several years. The aim, as ever, was to secure a loyal austere Muslim ally to Pakistan’s north, as a counterweight to India especially. But this could blow back, and threaten the stability of the Pakistan state.

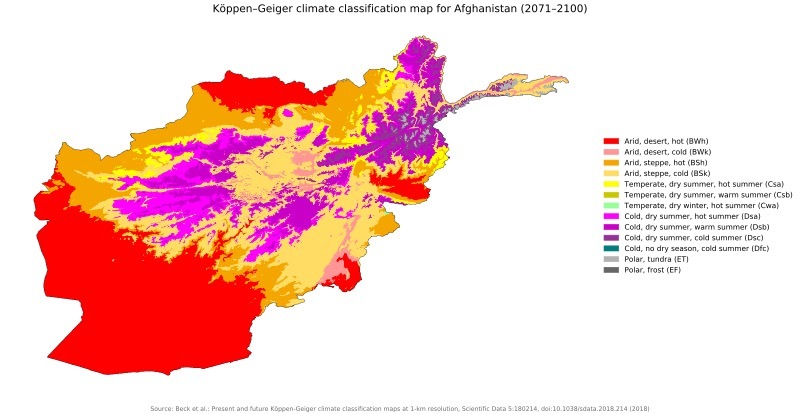

Afghanistan is now in the grip of severe drought, a cycle of 30 years. Crops have failed on a grand scale across the country. It is part of a growing effect of the melting of the glaciers of the great mountain chain of the Hindu Kush, Himalayas and Karakoram, from which flow at least 2,600 glaciers feeding the great rivers of Central Asia, including the Helmand. The collapse of the agricultural economy owing to drought greatly aided the Taliban advance this summer as desperate and impoverished farmers and villagers turned to the one form of authority in sight – the Taliban.

The Taliban offensive is one of the clearest military conflicts whose outcome was enabled, if not completely delivered, by climate change. The drought and famine this caused is in turn leading, as in several parts of Africa and Asia, to uncontrolled migration. The pressure of starving migrants could soon overwhelm the frontier stations between Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Source: Wikipedia

Source: NPR.org

Curiously, UK military planners and strategists seem more than willing to play down the effect of climate change as catalyst or cause of serious upheaval and violence. The droughts of Afghanistan and the ‘stans’, the states along the border to the north, were first mentioned to me by a three-star general just retired from the UK Army, but still responsible for Defence Ministry ‘Green’ policies.

I checked the record of what had been going on along the border with the great Steppe, and found a story of continuous and growing strife over scarcer resources, water especially, in Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan and along the Ferghana Valley. I recalled hearing ten years ago of the fights about water for sheep at shearing time in Faryab province, triggering communal battles between groups of Turkmen, Uzbeks, Tajiks and newly arrived Pashtun incomers backed by Taliban. This autumn I laid out in a number of articles my conclusions about the impacts of climate change in Afghanistan and Central Asia. My interlocutor, the former general responsible for MoD green policies said direct links between climate change and Afghanistan’s current plight are “exaggerated.”

Arghandab is one of the most famous regions for growing pomegranates – famed in song and legend beyond Afghanistan. A report in the New York Times of 21 November 2021, recounts the devastation of the drought, climate change, and the Taliban advance. Crops have been destroyed, others have yielded hardly any harvest at all – only two small piles in the case of a farmer who two years ago earned $9,300 from pomegranates, but last year only $620. Now the farmers are switching to poppy and opium – which earns less than pomegranate at their former best, but at least represents a steady income. “If the situation remains the same,” says one farmer, Hamidullah, “in two years there will be no trees (ie pomegranates) left.”

Afghanistan is still the biggest heroin source in the world, responsible for 80% of the world crop – despite all the millions of dollars in the complex and inconsistent counter-narcotics policies of the Americans and their allies. In 2020 the UN recorded some 224,000 hectares – about 900 square miles – being under poppy cultivation, up 37% on the year before.

The helter-skelter dash from Kabul has led to a widespread counsel of gloom in the Western commentariat, especially the US and Britain. Why go there in the first place? Wasn’t defeating the Taliban and setting Bin Laden on the run from Kabul in November 2001 enough? Don’t reinforce failure. Afghanistan was never a real nation or state, hopelessly corrupt and riven by tribal factions, a narco basket case, and the Afghans are responsible for their own fate. As Greg Mills and David Kilcullen stress in the introduction to their powerful essay, almost every single cliché of the commentariat and bien-pensants, many never having set foot near any part of the country, is distorted or plain wrong.

Afghanistan has been pushed and pulled by at least 26 dynasties as incomers and invaders. The British have now made at least seven military incursions and retreats in under 200 years. Most Afghans do regard themselves as Afghans as well as loyalists to tribe and place. Their country is a strategic hub, as its human geography displays decade on decade. The interaction of climate on conflict there now is a lesson for us all.

The US-led scuttle has damaged American standing and the credibility of the alliance in which it is both senior partner and leader, Nato. Nato needs to reinvent itself, examine its policies and practice. The underlying principle of solidarity is as sound as ever, but as Shafer and Col Grandia Mantas show, it now needs to make itself a suitable and active player in the present age of huge geopolitical and geographic change.

And back to the future with the legacy of its allies’ operations for peace, war and truth in the Balkans and Afghanistan. The story of the last two decades in Afghanistan and Iraq mean a rethink for concepts for international management of security and stabilisation practices. Nation-building may be a dirty word in the political lexicon nowadays. But to say ‘never again’, to the need and requirement of cooperative international effort for stablisation, security, and development flies in the face of history and future probability.

Robert Fox is Defence Correspondent for the London Evening Standard and author of The Inner Sea: The Mediterranean and Its People.