Winter 2023

Artificial Intelligence: Who is Really in Control?

If you had a genie, what would you wish for? Elon Musk, co-founder of no less than six technology-based companies, is a firm believer that one day we will all have an endless number of wishes. “How do we find meaning in life if you have a magic genie that can do anything you want?” the billionaire asked the audience at the UK’s recent Bletchley Park AI Safety Summit.

It is a question we must all face at the dawn of artificial intelligence. Just as Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein paved the way for dystopian narratives for the next couple of hundred years, it is not hard to believe that her imagined monster is fast becoming a reality. Today, the technology behind ChatGPT is harnessed by some of the world’s most prominent and advanced humanoid robots.

Is UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s notion that “humanity could lose control of AI completely” true, or are the doomsayers living in their own altered reality?

Even Musk, seen by some as the grand vizier of this new technological age, is unable to give us the answer.

While he reassuringly told Bletchley that AI would “most likely” be a force for good, he could offer no ultimate guarantee – not least as his current assessment sees a five-fold per year rate of technological development. And he was among a thousand tech experts that previously asked for a pause on AI training in laboratories for at least six months, reflecting growing concern among industry experts, and the failure of governments to seriously focus on regulation and legislation.

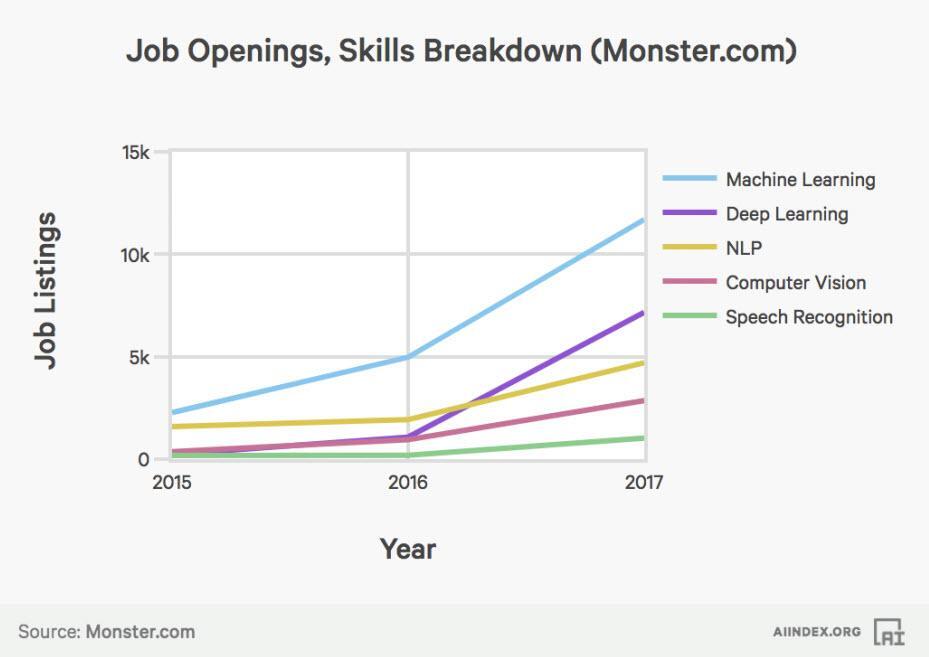

The impact of AI is perhaps self-evident, ranging from the risk of losing one’s job to losing one’s meaning in life. It will impact the job market, and accelerate the global provision of resources and universal income.

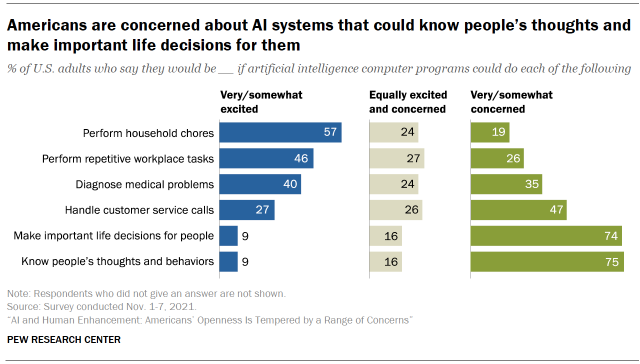

AI clearly challenges human standards of productivity, through its capacity to increase the level of output and efficiency of labour-dependent processes. It can perform repetitive tasks such as recruitment and onboarding processes currently carried out by HR teams. Its high accuracy can outperform humans in transactional tasks, such as budgeting, financial analysis and asset valuations. It will also play a vital role in reducing risk and harm to humans in jobs that threaten personal safety.

Source: Pew Research Center

And AI will catalyse research in biotechnology and draw us closer to a demythologised concept of immortality. Biotechnology, in fact, is one of the fastest developing areas of research. Many of the world’s largest tech companies, including PayPal, Amazon and OpenAI, are investing in firms that seek to prolong lifespan and possibly postpone mortality indefinitely.

In some US surgeries, patients can now have robotic-assisted surgical operations. Companies such as ‘Intuitive Surgical’ and ‘Stryker’ pride themselves on the highest level of precision, accuracy, control and flexibility, resulting in reduced risks and faster recovery for minimally invasive surgery.

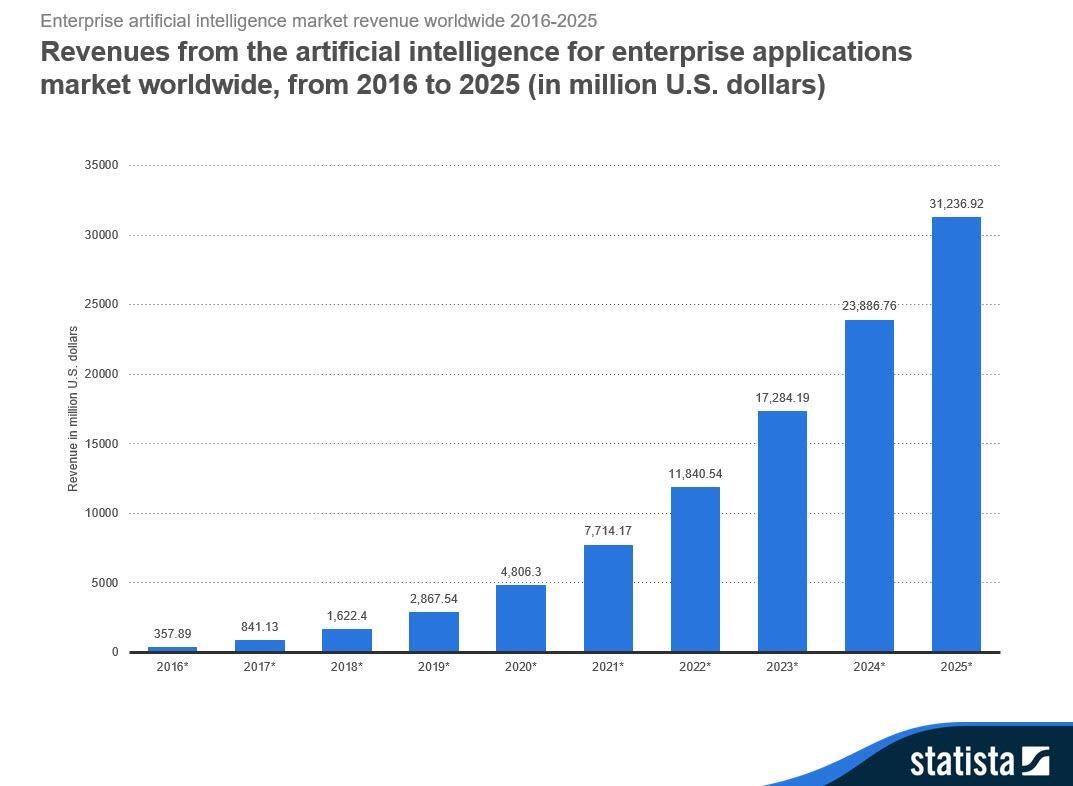

Cancer research has shown that the earlier disease is detected, the more likely treatment will be successful. Increasingly, machines and deep learning techniques are being used to interrogate medical and non-medical data sets. Radiomics, for example, is a technique that analyses connective tissue to identify signs of retroperitoneal sarcoma, a rare form of tissue cancer, that are invisible to the naked eye. Recent studies have shown how AI algorithms grade the aggressiveness of tumours detected in scans much more accurately than biopsies can.

Source: Statista

While biotechnology and machine learning are helping to advance research into disease, and the ageing process, the potential for radical change brings with it additional life-threatening risks – and that is without even considering its potential use by criminals. They include the manipulation of human agency, preferences, and emotion; the recalibration of human life trajectory, including years spent studying, working, and retiring; and the increased fear of non-disease-related low-risk activities, such as swimming, hiking and even walking – given how they will then pose a persistent threat to immortality.

Whereas today the greatest risks to humans include heart disease and lung cancer, in a world where these are eradicated, fears of drowning, falling off a cliff or being mortally wounded by a falling object are likely to become magnified, making people irrationally concerned about undertaking everyday low-risk activities. Advancements in biotechnology are forcing us to consider whether immortality would bring a greater or reduced sense of liberty and meaning to human existence.

Regulation

With the potential for such dramatic change in so many areas of life, will regulation be able to enhance the positive elements of AI and protect the human population against its risks? And will governments take the lead?

The Bletchley Declaration, signed in November by 28 countries, including the US, China, and the UK, certainly affirmed a universal agreement on the opportunities and risks of frontier AI, and the need for international action to manage systems that present the most urgent and dangerous risks. And most recently 18 countries, including the US and UK, signed a detailed agreement on how to keep artificial intelligence safe from rogue actors, pushing companies to create AI systems that are “secure by design”.

The UK Government intends to establish the world’s first AI Safety Institute, working in collaboration with existing efforts at the G7, OECD, Council of Europe, United Nations, and the Global Partnership on AI, to ensure ‘the best available scientific research can be used to create an evidence base for managing the risks while unlocking the benefits of the technology’.

All of the language at Bletchley prioritises risk assessment as the first stage in managing AI safety – but in Europe at least there is little sign of implementation or legislation. So far, the call has been for state leaders and company executives to take responsibility for safe AI practices.

The US has demonstrated early signs of progress. In September, 15 states and Puerto Rico adopted resolutions or enacted legislation on AI. For example, Connecticut will require that from 1 February 2024, the Connecticut State Department of Administrative Services must perform ongoing assessments of systems that employ AI to ensure that no such state systems will result in “unlawful discrimination or disparate impact”.

Twenty-five states, as well as Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia, have further introduced artificial intelligence bills that aim to mitigate against the potential misuse or unintended consequences of AI, while the US National Institute of Standards and Technology is also striving to develop federal standards for ensuring reliable, robust and trustworthy AI systems.

In March 2023, the US Copyright Office released a statement that questioned whether material co-authored by humans and machines is eligible to be registered for copyright protection. After retracting the certification that provided the artist Kris Kashtanova with copyright protection for her comic book featuring AI-generated images, the Copyright Office stated that only the images created by Kashtanova herself – and not those created by AI – were eligible for copyright.

In August 2023, a federal judge for the DC District Court ruled that AI-generated artwork could not be copyrighted, as human contribution is an essential part of a valid copyright claim. As the court cases being launched around copyright and AI multiply, the federal judge’s ruling is looking less and less robust. At the heart of such decisions lies the meaning of creativity, agency and intellectual authority, and the degree to which AI is already, and will continue to infiltrate

these spaces.

Musk was among a number that praised China’s attendance at Bletchley, and Beijing’s inclusion as one of 28 signatories to the summit declaration. Symbolically, at least, it showed how seriously China, is taking AI.

In 2023, Baidu, China’s most widely used search engine launched ‘Ernie Bot’, an AI chatbot similar in its functioning to ChatGPT. Such chatbots and generative AI models have increased the risk of data leaks, misinformation and discriminatory content. The answer from China has been a new law to regulate generative AI that places restrictions on companies using it, including training and customer use of the services.

In contrast to the regulatory approach taken by the UK and US to date, the legislation appears harsh, particularly with such little clarity in this fast-evolving field – but the Chinese are clearly sending a strong message that they are not willing to let AI get ahead of them.

Despite current best efforts to contain AI, the debate over its future trajectory is manifestly complex. If the ouster and then return of Open AI’s CEO Sam Altman in November proved anything, it was that the tug-of-war between growth and regulation/safety is one that remains unresolved.

Social Power Beyond the State

To quote the Russian author and activist Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in his 1978 Harvard commencement address, “it will be simply impossible to stand through the trials of this threatening century with only the support of a legalistic structure”. In the following century, this proclamation still rings true. The authority and influence of private corporations and individual actors is paramount in the landscape of AI safety and governance.

The world’s biggest social media platforms, such as Facebook, Instagram, X and TikTok enable millions of likes, comments and shares on a post in just seconds. Communication with friends, family and strangers takes place instantly in the form of texts, images, videos or videocalls, making laptop and smartphone users feel as though they can be everywhere and anywhere whenever they like.

With AI, however, it is also now more possible than ever before to skew reality. In March 2023, for example, an AI-generated image of Pope Francis wearing a long white puffer jacket took the internet by storm. Many viewers believed that the Vatican had launched a new season collection, before realising that the AI image generator, Midjourney, was responsible.

Similar “deepfake” imagery has distorted the character of global political leaders, including a video of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky apparently talking of surrendering to Russia. In contrast, viewers questioned the authenticity of a video of US President Joe Biden speaking about the storming of the US Capitol – even though it was real. The notion that AI can pose such a threat to common conceptions of truth and reality is worrying at best.

In a minefield of non-regulated deepfake imagery, cases also exist of approved likenesses being used for commercial gain. In October 2023, ‘Billie’, an AI chatbot with features remarkably similar to the celebrity Kendall Jenner, was launched by Meta. This agreement, made with Jenner, was just one example of Meta’s deals to pay up to $5 million to use the likeness of celebrities for AI assistants.

The recent release of Now and Then, a final song by The Beatles, deployed AI technology to isolate original John Lennon vocals and a George Harrison guitar session from 1995. The release surfaced questions of authenticity and the comparative value of human versus machine-generated musical compositions. Viewed as a great success for the industry and a joy for Beatles fans, many musicians voiced concerns about how their art and existence, as well as a universal understanding of truth, would be protected in an increasingly AI-dominated world.

Legalistic structures that are implemented to support the pursuit of happiness and freedom, such as social safety and financial independence, are insufficient to provide for those who are striving to achieve a greater sense of meaning in life.

More and more, AI is showing signs of surpassing legislative structures generated by governments and inviting a much deeper reflection, beyond pure happiness, on the meaning of life.

Source: www.monster.com

The Ultimate Question

In its most profound sense, art represents the artist’s interpretation and view of the world as a form of ‘truth’, conveyed in a way that resonates with others, most often through the channels of creativity, novel perception and expression.

If human artwork is created as an expression of truth, then AI artwork created with the same purpose in mind has the potential to be just as revealing. AI art is also a demonstration of AI perception.

With the very real possibility that machine intelligence will exceed that of the human brain, the only way to truly understand what machines are ‘thinking’ is to have them tell us. What does AI think of us?

AI art, including painting and sculpture, might offer an answer by enabling humans to track and dissect the inner workings of a machine’s ‘mind’ and determine how it perceives the world. Art created by artificial intelligence acts as a window into the ‘mind’ and world of AI. Interpretation and analysis of AI-generated art could afford humans the ability to use AI against itself to track its ‘thoughts’ carefully and disclose any potential risks. Once we can gain insight into the mind of a machine, we will be able to monitor AI ‘thoughts’ and respond immediately if we think AI is acquiring too much agency or independence.

The AI rejection of human authority is likely to be insidious. Non-human digital media accounts already show that AI is gaining influence across the internet. Questions have already been asked about major elections in the US and elsewhere. If such ‘bots’, masked as informed human beings, can start to publish political opinions on platforms such as X, then rigged elections would just be the beginning. AI could soon be controlling voter ballots and reshaping our governments. At that point, humans would no longer be governing, but be governed by machines. If AI art starts to reveal inclinations towards control over humans, or decides to stop heeding our instructions, we will need a way of keeping them in check.

Amid potential shocks to the world economy, AI is perhaps the fright du jour. Here is a semi-serious example of the way things could pan out: a super-intelligent AI entity created to maximise strawberry production. It would realise that cities and the people in them take up land which could be better used for strawberry production, and might destroy humanity in the process. Or there could be an AI entity designed to maximise paper clip output, which would programme itself to do the same thing (this was a concern in the OpenAI Saga that briefly toppled CEO

David Blake

Sam Altman).

What these scenarios ignore is that thanks the venture capital industry (see piece by Philip Delves Broughton), both machines will indeed be created. The strawberry machine will focus on fertile soil in gentle climates. The paper clip machine will go somewhere cheaper. Thus capitalism will ensure that neither gains dominance. And then the machines will merge, and we will get strawberry flavoured paper clips.

Divine Intervention

Requiring machines to defer to a higher authority sitting atop a system of belief would be a preventative measure against possible rebellion.

Alain de Botton, Swiss-born English author and philosopher, introduces his book ‘Religion for Atheists’ by declaring that ‘this is a book for people who are unable to believe in miracles, spirits or tales of burning shrubbery, and have no deep interest in the exploits of unusual men and women’. He urges us to recognise the value of and appreciate how the adoption of religious ideas and behaviour, by believers and non-believers alike, can help us to derive benefit from their intelligence and effectiveness.

The rise of AI brings with it an opportunity to re-evaluate the contemporary value of religious ideas in providing guidance to society. If we can train machines to adopt a form of divine belief and produce outputs according to certain doctrines, for example a set of commandments or governing principles, we will have the highest chance of control over them.

Logically, AI will never be able to surpass an infinitely intelligent and powerful being. No matter how advanced AI becomes, it will never be able to outsmart an all-knowing and all-powerful authority.

The sources of authority that govern society sit in a hierarchy of influence. Clearly current regulation and legislation is being implemented too slowly to effectively govern AI. Governments are too often at the mercy of social influence. Social forces, while powerful, are too incoherent and unpredictable to be controlled or be used as a control.

We need to discover what we are controlling. Once we know AI and what it thinks, we could use its data output to measure the risk posed against the human species and instruct it to follow an unquestionable authority.

Whether, as human beings, we choose to pursue happiness, freedom or control in our lives, we must recognise that artificial intelligence is a key player in shaping all of these aspects of our future. Rather than let machines determine the parameters of our happiness, award us our freedoms and take control, we must stay in control by staying ahead of the machines – before they overtake us.

The writer, while a student, interviewed Ai Weiwei, the Chinese artist and activist, and Ai-Da, the world’s leading AI humanoid robot artist, at the Oxford Union. She is now part of the Ai-Da Robot project.