Winter 2023

Private Equity: Survival of the Fittest

During the leveraged buy-out heyday of the mid-1980s, the debt was primarily high yield bonds, derisively called “junk”. You issued the junk, with high rates of interest, to make the acquisition, then rapidly paid it off by flogging off or restructuring what you had bought. It was a nerve-jangling game for Gordon Gekko-like characters.

The 2007–9 financial crisis introduced a new era of historically low rates and easy money. Debt became virtually risk free. Asset prices went up. Obligations could invariably be extended or rolled over. The LBO pirates were replaced by executives who were indistinguishable from ordinary investment bankers – but for the size of their compensation.

Private equity went from being a truly alternative asset class, with its own very particular risks and rewards, to being part of the investing mainstream.

But the battle against inflation, waged with surging interest rates, has reset the industry again. Can a private equity industry that has become institutional, well-mannered, and acceptable continue to thrive when the market conditions have returned to those in which the industry was born: volatile, and prey to jolting market forces. Can these sleek, corporate mega-yachts survive in waters which would challenge an icebreaker?

There are plenty of people rubbing their hands in hope of a humbling. The PE firms have done so well for so long now that they have incurred plenty of envy. But the best of them are anything but complacent. Unlike banks which mostly stagger along, bound by regulations and cultural inertia, the private equity firms have adapted to their new environment in three crucial ways.

First, they have expanded their sources of capital. They have gone beyond the traditional sources, the institutional investors, sovereign wealth funds and family offices. Some, notably Apollo, have invested heavily in insurance to acquire huge new pools of capital, the premiums paid by customers. Others have marketed themselves aggressively to wealthy, but not insanely wealthy, investors, with more accessible products.

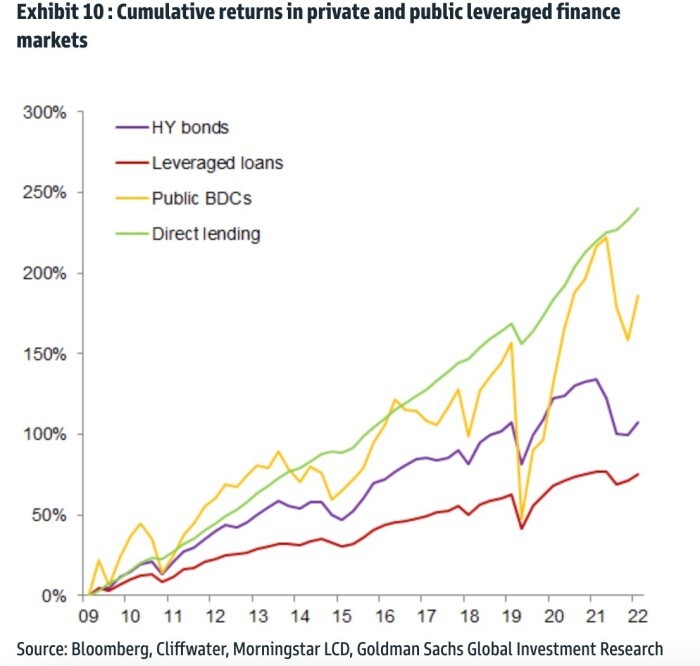

Second, they have gone into new lines of business, notably credit. After the crisis, banks came under pressure to reduce their balance sheets. They withdrew from many forms of lending. The void has since been filled by private credit funds, which can offer more flexible and esoteric forms of credit.

Private credit is now a booming industry of its own, with stand-alone private credit businesses thriving, and fast-growing funds within companies previously best known for their real estate or private equity practices.

Corporate borrowers are finding they can get better terms, more imaginative deals and faster execution with private credit firms than they ever could with the more slow-footed banks, which are now regretting their years of retreat.

The entrepreneurs of private credit, along with higher rates, have reminded the banks that lending money can be a terrific business.

Third, hard times have forced the private equity firms to get creative. Holden Spaht, managing partner at Thoma Bravo, one of the most aggressive technology-focused PE firms, wrote recently in The Financial Times: “Confronted with macroeconomic headwinds, an intolerant initial public offering market and lower valuations, the psychology of other investors and other decision makers tends to tilt towards greater risk acceptance. So, under heightened market pressures, it’s increasingly important to remind ourselves that there are no shortcuts when it comes to responsible risk strategies.”

But merely by mentioning the “tilt towards greater risk acceptance” and the fear of “shortcuts”, he put his finger on what critics of the private equity industry fear is now going on.

Source: Bloomberg, Cliffwater, Morningstar LCD, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research

In order to survive, the biggest firms are reaching into their bag of tricks. Everything they do now is being scrutinised and often compared, fairly or not, to the run up to the crisis when the financial system was undone by its own flawed engineering.

We are seeing a surge in practices which those on the inside pitch as smart risk management, but many on the outside consider too clever by half.

The heart of the problem is liquidity. No one wants to sell the assets in a fund under duress. But with buyers scarce and borrowing expensive, the PE firms are scrambling for ways to sustain the value of their portfolios until conditions improve.

In certain cases that means flipping certain assets to other PE firms in the secondary market, getting cash while retaining some stake in a private company.

In others it means finding more creative sources of borrowing. There has been rapid growth in Net Asset Value lending, in which PE firms borrow against the value of their portfolios, rather than its individual parts. The biggest questions here tend to revolve around the accuracy of the valuations attributed to pools of private assets.

Credit funds are now reportedly seeking cheaper lines of credit for themselves by borrowing against collateralised pools of their own loans. Again, accurate pricing and risk management are an issue.

Defenders of these practices represent them as a smart diversification of funding, and the best way for investors to realise gains in challenging times.

To the uninitiated, they smack of the kind of Wall Street witchcraft which precipitated the financial crisis. Debt upon debt, collateral against collateral, until somewhere at the bottom of the Ponzi pile you find an abandoned home in a Las Vegas development now worth next to nothing.

But while many in private equity are fixated on interest rates, the smartest are already looking at what happens on the other side. Where rates remain higher for longer, or start to fall, there will be opportunities.

The long era of low rates was forgiving for poorly run companies. High rates exert a brutal discipline which should eventually serve the PE firms well. So far, the shake-out has been modest. Economic logic, however, dictates it should intensify.

Big corporations will want to sell their underperforming, capital intensive businesses, ideal targets for PE funds with billions of dollars in dry powder. The rude health of the technology giants has covered up the many companies still languishing on the public markets. Lots of these could thrive under private ownership and their executives would welcome the personal financial possibilities. We are even seeing firms which went public as recently as 2021 yearning for the freedom of a return to private ownership. The scrutiny of the public markets is simply too draining, especially when it comes without a financial windfall.

The real head scratcher for economists and private equity funds these days, however, is why valuations have not plummeted as interest rates have risen. Normally, the more companies have to pay to borrow, the lower their profits and the cheaper their stocks. But this is not what has happened.

One explanation is that investors are confident that higher rates are not going to impede economic growth, particularly in the United States. The data over the past couple of years suggest they are right. While inflation has cooled, the economy has continued to thrive.

A major reason for this is the anticipation of a fresh surge in productivity driven by Artificial Intelligence. No one wants to sell at a moment when we could be on the brink of a leap in corporate valuations as costs fall relative to revenue.

The private equity hunters following the herd are not finding the wounded beasts they are used to capturing. They have the right weapons, the investors, the cash and the credit, but they are not the only ones in pursuit. Others can see what is happening, and the rules of the game are changing under pressure.

While many in private equity are fixated on interest rates, the smartest are looking at what happens on the other side.

Assets which should be cheaper because of the higher cost of debt, are not because of the competitive pool of buyers. GDP numbers which should be stagnant as consumers hold back on spending are not because of this general hunch about a new technological era.

All of which leave the PE industry in a new place. What was a club containing a few men in New York is now a global economic force, as potent in Europe, Asia, and the Middle East as it is in the Americas.

The firms which were built on private equity now contain much larger businesses in real estate, credit and insurance. Executives from these newer lines of business often run the show.

There is also much more scrutiny. Private credit flourished in obscurity but has now reached such scale that regulators are asking what exactly is being lent on what terms to whom. Individuals will be picked out and made examples of. Banks will not be unhappy to see the upstarts knocked back a bit.

The war horses of private equity will be able to look on knowingly, having taken their public hazing and emerged no longer dangerous and threatening but now permanent features of the investment landscape. Some might yearn to get through this high-rate period with the bare-faced aggression and junk bonds of the 1980s. But the cooler heads will say just wait. Let credit have its moment, reset, survive, and be ready on the other side.

Philip Delves Broughton is an author and journalist. He is a Senior Consultant to Brunswick, based in New York. He was previously a Senior Adviser to the Executive Chairman of Banco Santander. His books have appeared on The New York Times and Wall Street Journal bestseller lists and been published around the world and include Ahead of the Curve and The Art of the Sale.