Winter 2023

Chastened but Unbowed: International Finance Rolls On

Ever since the Six Day War in 1973 plunged the world into an energy crisis, the world’s economic policy makers have seen the need to protect the financial system from shocks starting in the outside world. On this, they have done a pretty good job. On protecting the outside world from shocks starting in the financial system, not so much. As the world discovered to its cost.

The most obvious way to assess the performance of the financial system is to look at how much markets rise or fall. It is also the most misleading. Because it is the ability to change prices which makes markets a shock absorber not a shock creator. Disasters make us poorer; inventions make us richer. And as a rule the sooner we recognise what has happened and get on with life the better for all concerned.

But for that general rule to hold, the actors within the system must either be strong enough to withstand changes in the price of assets, or small enough not to matter. For regulators this need provides a constant source of tension. Should strong institutions take over weak ones? Doing so might resolve a problem or it might simply drag down the strong one to a level where it poses risk to the system as a whole.

The oil shock of the 1970s caused great problems for the world’s monetary and financial system but also showed its remarkable ability to withstand shocks. A comparison of the first two great shocks of the 21st century, the Great Financial Crisis and the Covid pandemic, shows some of the strengths and weaknesses of the system. What does this presage for the future?

The philosophy which underlies official handling of the financial system is simple. It is that the banks, which provide the wiring through which all transactions flow must be protected from all dangers, including those that come from themselves. It is a theory which risks becoming outmoded by the very measures taken to enforce it. For as regulators try to curb the risks banks take, risk-taking moves to other areas beyond the reach of regulation.

The theory owes much of its appeal to the experience of the 1930s when the banking system collapsed under the weight of bad decisions. It is this banking collapse, not the more often cited Stock Market Crash of 1929, which lay at the heart of the Great Depression.

From this follows a game of regulatory whack-a-mole which has been going on ever since. Bankers try to boost profits by taking on more risk. Regulators try to force them to stop and others come in to take on the risk. Bankers then see their business vanishing to the competitors which have been fattened by the opportunities which the regulators have given them. The banks appeal to be allowed to compete again, pointing out that their importance is diminished.

In the US, which dominates financial markets, this pattern is seen very clearly. So bad was the 1930’s banking crash that the Glass-Stegal Act of 1933 forced a choice. Either be a bank, cashing cheques and making loans against security. Or go all in as a risk taker, becoming what was known as an “investment bank.” These institutions had a chance to make big money by using their own money to bet on markets. And they offered both nations and corporations an alternative way to raise cash, by issuing bonds rather than getting loans. As a price for this, they were excluded from borrowing from the Federal Reserve. This distinction reflected the belief that the investment banks, not being really banks, could be allowed to fail without threatening the system.

For a long period after the war these two kinds of institutions coexisted reasonably harmoniously. But pressure on the banks grew in the 1970s with an explosion of borrowing as industrial and developing countries ran up huge deficits because of the high oil price. Those deficits were matched by huge surpluses for the OPEC countries.

Source: AI generated image

The banking system was stretched by this phenomenon. It meant that banks had made loans and taken deposits far larger than their capital base justified. And thus the official response was to seek a way to reduce this risk by “disintermediation.” That meant cutting out the banks as middle men so that borrowers got their cash directly from those who owned it.

That meant replacing bank loans with bonds sold to investors. Financial markets are just as keen to visualise their customers as anyone else. For the wave of bond offerings needed to recycle cash within the western world, the dream buyer was described as the Belgian Dentist. Given the highly questionable nature of many of the offerings, he was an ideal customer. Few people have relatives in Belgium and everyone hates dentists. For the moralistic, there was the added attraction that the money was widely thought to be the proceeds of tax evasion.

But the appeal of bond markets was far wider. Banks had a nasty habit of calling in loans at the most inconvenient time. For a corporation, once the bond was sold the money was safe until the bond fell due. Thus from the late 1970s the conventional banks saw their business eaten away by the investment banks. They responded by demanding that the shackles on their activity be removed and this was done under the Clinton Administration.

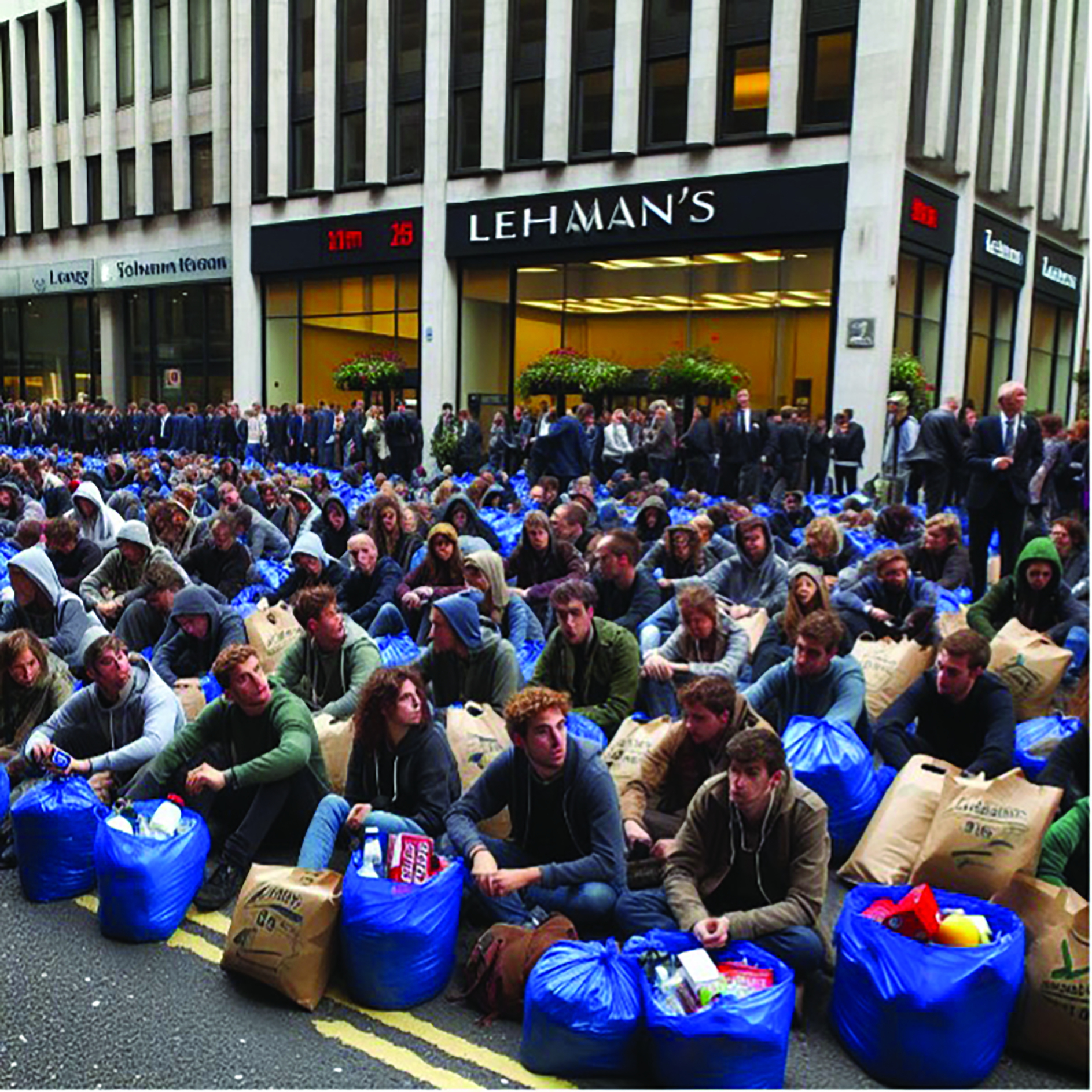

By the middle of the first decade of this century the only real distinction between investment banks and banks proper was that investment banks could not borrow from the Federal Reserve using bonds as collateral. Just how much that mattered became apparent when Lehman Brothers which owned bonds and other assets worth $630bn could not pay debts because it ran out of cash. Which in turn brought down many other institutions which relied on money they expected to receive from Lehman.

Many people assign the creation of dubious mortgage bonds to the role of instigator of the Great Financial Crisis. But in fact the quantities involved were relatively small, about $400bn. What really posed the problem was that financial institutions had used complex tricks to pretend that money locked up in bonds could be turned instantly into cash. Which was fine until everyone tried to do it at the same time.

The only way to save the system was to pour money into it. And this governments and their central banks did so effectively that almost all the players in the banking sector survived. But there were prices to pay. For the financial sector, the price was tighter regulation aimed at reducing the risks took on their own books.

But bank still need to make to make profits. To do this they have courted outside risk-takers who are willing to pay them fees. Two examples of the danger this poses can be seen in the following.

Credit Suisse was one of the world’s leading investment banks until a series of missteps culminating in a client to run up losses of $11bn, which was a key factor in bringing the bank to its knees. It seems that the fact that somebody else was losing the money outweighed the fact that it had been borrowed from Credit Suisse.

Simply being aware of the risk of loss is not enough, however. Indeed it can sometimes cause problems rather than resolve them. This is shown by a UK example, which incidentally played a role in bringing down the government headed by Liz Truss.

UK pension funds became so used to the idea that interest rates would stay low forever that they entered complex contracts promising to buy even more than they owned. But when interest rates went up following tax cuts announced by the Truss government, they did not have the cash to pay. Panic selling forced the Bank of England to step in.

The crisis is a result of one of the good changes brought in after the GFC. In the past many instruments were traded just on the word of the two parties. If one went bust, the other could not collect. Now they are traded on exchanges where payment is guaranteed but enforced quickly. The Bank is only now carrying out a very belated exercise to discover the consequences of this.

Source: AI generated image

What about the effect on official policy of the need to rescue finance from the crisis which it brought upon itself? It was deeper than people realised and probably the impact is still not fully appreciated. Until the crisis came along, governments and central banks were confident they had macroeconomic policies right. Tight government borrowing and central bank pledges to hold down inflation were the order of the day.

So great was the financial crisis that all this was thrown out the window. Huge quantities of money were poured into the system. Central banks volunteered to lose massive sums by buying government bonds which they knew would lose value if the economy recovered, safe in the knowledge that governments would cover their losses. For example the UK government recently wrote the electronic equivalent of a cheque for £170bn to cover losses by the Bank of England.

Nor, I would argue, did the impact stopped there. The fact that government found virtually unlimited funding for the financial crisis meant that when the pandemic burst upon the world, all the restraints on government spending had already been blown away. The costs of these two episodes will be felt over the coming years in higher interest rate bills.

Yet both the pandemic, and recent conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza, show the extraordinary ability of the financial system to cope with external shocks. The pandemic crippled the productivity capacity of the world’s economy and it has not fully recovered yet. But output is back above pre-crisis levels in most places. Conflict with Russia sent energy prices soaring. Yet those prices did nothing to threaten stability of the system. The oil price went up and then came down. The prospect of it being somewhat higher in the future has simply intensified the search for alternatives.

David Blake is an executive director of Goldman Sachs and a former economics editor of The Times of London. He is writing in a personal capacity.