Winter 2023

A River Runs Through It: Gaza and the Jordan’s Path to Peace

In 2019, when I visited Nir Oz, one of the kibbutzim close to Gaza that was attacked on October 7, botanist Ran Pauker, a long-time resident, told me: “We are stupid. I have a good friend in Gaza. We once worked together on the management of pine trees. You should never fight with your neighbours. We are only making the next generation of angry soldiers.”

The octogenarian thankfully survived the recent assault, but fully one hundred Nir Oz residents, a quarter of the total, were kidnapped or murdered. The accuracy of his words four years ago is abundantly clear. He understands better than most that in terms of long-term security, Israel’s present response to October 7 is set to be self-defeating.

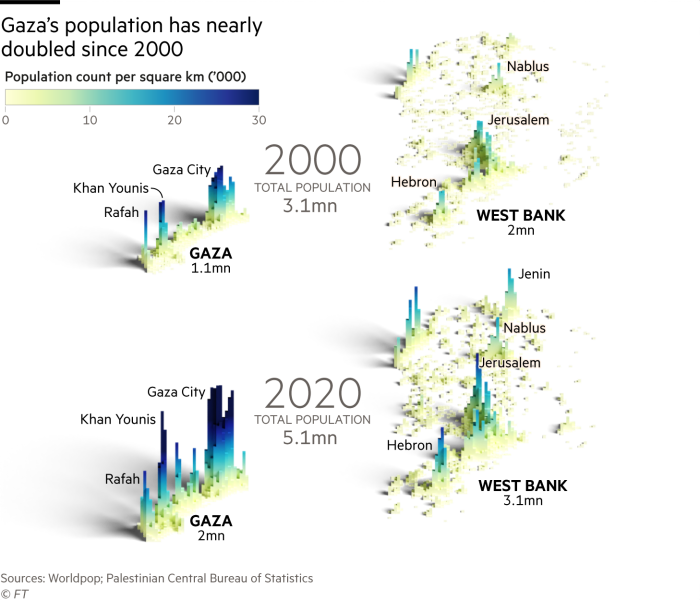

Coexistence requires an equitable distribution of the land and its resources; an imperative that increases as the land becomes more crowded, and the pressure on resources grows. Israelis, if not all foreigners, understand that their country is tiny; a much-reproduced overlay map shows that it is rather narrower than greater Los Angeles. Israel-Palestine, with a population of some 14m, is already crowded – and the number is growing at dizzying speed, above all in Gaza, where the median age now is 18, and is projected to double by 2050, to 4.8m. The total population is on track to exceed 20m by 2040, by which time Israel-Palestine will be one of the most densely populated regions on the planet.

The housing stock of Gaza City is now half-destroyed, along with schools, hospitals and much other essential infrastructure – including, crucially, water and sewage infrastructure. The World Health Organization says that 20 litres of water per capita per day is the absolute minimum required to take care of ‘basic hygiene needs.’ This November, however, Gazans were down to an average of just three litres per day.

Internally displaced and crowded together, their immune systems are already weakened by hunger. Raw sewage runs in the streets, adding to the stench of bodies decomposing beneath the rubble. Doctors working in the enclave’s collapsing healthcare system have warned for years of the risk of a water-borne epidemic that could kill far more Palestinians than Israeli ordinance ever will. Conditions are now riper than ever before. Nature has already issued a warning: in the month to mid-November, 44,000 cases of diarrhoea were documented, half of them among children under five, according to the World Health Organization. The usual monthly rate is 2,000 cases per month. The UN warned in 2015 that Gaza could become literally ‘unliveable’ within five years. That prediction was exaggerated, but not by much. Catalysed by war, it could soon become true.

“A quarter of all disease is waterborne,” Gidon Bromberg, the director of the NGO Ecopeace, which has long lobbied the Israeli government for a change of approach in Gaza, told me. “Much of Gaza’s supply is private and unregulated. Once disease takes hold, the genie will be out of the bottle. In Gaza, we are playing Russian roulette.”

Israelis may imagine they could keep themselves separate from a Gazan epidemic, but the experience of Covid suggests otherwise. Contagion loves a crowd, and pathogens are no respecters of border fences. Nor is Gazan sewage. At least four times since 2015, human effluent, pumped untreated into the sea, has floated north up the coast to the Israeli city of Ashkelon, where it clogged the intake pipe of a desalination plant so seriously that the plant briefly had to be shut down. In 2016, Gazan sewage overflowed the northern land border via the Wadi Hanoun. Bulldozers were overwhelmed; a fleet of twenty tankers was sent to hoover up the filth and deliver it to the Sderot treatment plant, where the extra effluent so overloaded the system that a pipeline burst; groundwater was contaminated so badly that the Ministry of Health was obliged to shut down four large local wells for three years. For many Israelis, this was a moment of realisation that Gaza’s water and sanitation issues are Israel’s problems too. Aquifers, of course, run beneath political borders all over Israel-Palestine; they are part of a regional hydrologic system that cannot be sliced down the middle. Not for nothing does Eran Feitelson, a senior geographer at Jerusalem’s Hebrew University, describe Israel and Palestine as being ‘like a Siamese twin with one shared organ’.

Israelis, to date, have conspicuously not fairly shared the fruits of that hydrologic system. As early as the 1930s, the region’s only major river, the Jordan, was dammed by the pioneering Yishuv for their own agricultural purposes. Then, from the 1960s, Israel began pumping out billions of gallons of the Jordan’s feeder lake, the Sea of Galilee, and sent it west and south via an immense new canal, the National Water Carrier, to fuel the extraordinary expansion of their country. The West Bank, in consequence, is a riparian entity in name only; the once mighty river that delineates its eastern border has for decades been little more than a muddy ditch.

Any aerial shot of the Gaza border area serves to illustrate the gross disparity of water access that this has led to. The farmland on the Israeli side is a picture of order and scientific efficiency. Settlements like Nir Oz – which once specialised in the production of asparagus – nestle in a patchwork of huge green fields, all perfectly irrigated. Some of the fields are round and resemble pie charts, with segments of different colour where crops have been planted in rotation. The water that irrigates them is delivered by the National Water Carrier, which terminates close by. It is the apotheosis of the famous ambition of Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, to ‘make the desert bloom’.

The dominant colour on the Palestinian side, by contrast, is concrete grey. Chaotic tendrils of urban development stretch from the coast all the way to the fence, where a few fields cling on. These fields, the Strip’s supposed breadbasket, are the size of postage stamps, and they are mostly dun-coloured; none has the lush hue of the mega-fields to the east. This study in hydrologic haves and have-nots does not by itself explain the brutality meted out on October 7. But, taken together with the desperate conditions in Gaza itself – the poverty, the lack of opportunity, the despair and sense of entrapment caused by the siege – it does perhaps inform it.

Palestinians talk a great deal about the restoration of their water rights. It is egregious that, thanks to the one-sided terms of the Oslo Peace Accords of 1995 (which de facto still exist), West Bank Palestinians are mostly prevented from drilling for the water beneath their feet. Instead, some 87 per cent of the available water in the supposedly shared central mountain aquifer is extracted by Israel. The Palestinian Authority in Ramallah is obliged to make up the shortfall by buying in networked water from Mekorot, the Israeli state utility.

Restoring Palestine’s water rights within the framework of a renewed peace process is important, but it would not by itself solve the shortage. There are, already, about 4m more people living in Israel-Palestine than Nature on its own can sustain, a shortfall that is growing all the time. Israel, happily, realised this some time ago, and turned for answers to what it has always excelled at: technological innovation. Israel’s water sector is the envy of the world. The country leads the way in advanced recycling, drip irrigation and many other resource management techniques. Most significant of all, the country since 2005 has built five huge desalination plants on the Mediterranean coast, with a sixth due to open in 2025. These days, as much as 80 per cent of Israel’s domestic water is ‘manufactured’. Israelis make so much of it, indeed, that – uniquely in the water-stressed MENA region – they enjoy a water surplus. Their dependence on the National Water Carrier and the Sea of Galilee is no more. The Israeli Water Authority now even pumps desalinated seawater back uphill via the National Water Carrier to the Sea of Galilee, in a bid to reverse decades of overextraction.

Beyond the destruction of Hamas, it is still unclear what Israel wants to happen. Should an epidemic take hold, however, Israel’s ability to dictate the pace could quickly be overtaken. Bromberg suggested to me that an epidemic could lead to hundreds of thousands of Gazans ‘moving to the fences… with empty buckets, desperately calling out for clean water. And what then?’

Beyond the destruction of Hamas, it is still unclear what Israel wants to happen.

t seems that some in the Israeli Defence Force (IDF) understand the threat to domestic security that such an event would bring. ‘The Great March of Return’ that Hamas called for at its fence demonstrations throughout 2018–19 would become a reality. The Covid outbreak in 2020 caused consternation enough. At the beginning of that year, the left-leaning daily Haaretz reported that ‘the scenario [of a Covid outbreak in Gaza] is being filed by the security establishment under the label, “God help us”.’ Covid, when it eventually reached Gaza, did not prompt the public health disaster that the IDF feared; but a waterborne epidemic would likely be very different.

It is puzzling, then, that the conditions for such an outbreak have been set not by an act of God, as with Covid, but by IDF tactics. There has been much media speculation that it is deliberate: a precursor, perhaps, to the elimination of Palestinians from Gaza altogether. “We are now rolling out the Gaza nakba,’ the Israeli security cabinet member Avi Dichter declared in mid-November, a reference to 1948, when some 750,000 Palestinians fled or were expelled from their homes in what would become Israel. When the IDF declared that its hunt for Hamas would extend from northern to southern Gaza, it appeared to Palestinians that Israel could be seeking to force another Exodus as well as a new nakba, by driving the Gaza population onwards into Egypt.

For now, however, that seems unlikely to happen. Egypt has no interest in acquiescing and has shown no sign of doing so. The instability such a mass transfer would bring would be hard if not impossible for Washington, let alone Arab states, to tolerate. Saner Israelis know that eventually, a new way must be found for Israelis and Palestinians to co-exist.

Neither mass expulsion nor the IDF’s ongoing campaign of destruction appear to serve that end. The US General Stanley McChrystal, who headed international forces in Afghanistan in 2009-10, once calculated that for every innocent his forces killed, ten new enemies were created: a simple cause and effect process that he dubbed ‘insurgent math’. When the IDF’s campaign is over, how will Gaza’s survivors view Israel – or indeed her allies in the rest of the world, who until now have so signally failed to restrain the killing?

Competition for water has been at the heart of the rivalry between Israel and Palestine for more than a century. That story is familiar everywhere in the world: the very word ‘rivalry’ derives from Latin rivalis, ‘those who share the same stream’. But in Israel-Palestine, this old competition is being pushed into irrelevance; engineers say that water supply is no longer a ‘zero sum game’. Water technology thus offers the promise of enough water for everyone: a basis for co-existence, and thus perhaps a potential pathway to peace — but only if the political will for it exists. Once the IDF campaign in Gaza concludes, what path will Israel’s leaders choose?

James Fergusson is author of In Search of the River Jordan: A Story of Palestine, Israel and the Struggle for Water published by Yale University Press