Winter 2023

Migration: Misunderstandings, Myths and Malice

On Tuesday 12 September 2023 5,000 migrants from North Africa arrived in 112 boats at Lampedusa, the southernmost point of Italian national territory between Sicily and Tunisia. Within three days a further 7,000 migrants landed on the same island, whose resident population is little over 6,000.

The impact of hurricane-strength Storm Daniel – a novelty in the region – had caused a bottleneck in the migrant smuggling trade launched from Tunisia. Once the weather cleared the smugglers filled more than 120 boats in a day and a half.

Lampedusa has been a chosen staging post for undocumented migrants in flimsy boats trying to reach EU Europe by sea. The surge in arrivals last September has become the epitome of a strategic shock of migration, compounded or catalysed by climate change.

Through the autumn, the concerns about migration turned to shock, and were greeted with panic, and a touch of hysteria in public and social media. In Italy Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni struck a deal for asylum seekers reaching Italy to be processed at one or two holding centres in Albania. Interestingly, she only informed the EU Commission after she had signed the deal.

In Britain the government struggled to fulfill the pledge to ‘stop the boats’ – a phrase borrowed from Australian conservative governments – to stop migrant smuggling across the English Channel. In November the British government itself revealed that net legal migration into the UK for 2022 was 745,000. This is about 25 times the number being ferried across the Channel in smugglers’ dinghies.

The same month in the Netherlands in November the leader of the ultra-nationalist and anti-immigrant Party for Freedom, the PVV, Geert Wilders topped the polls with 37 seats in the 150-seat parliament. He wants to stop immigration, return asylum seekers and quit the European Convention on Human Rights. The number of asylum seekers had doubled in one year to 77,000.

Dublin witnessed an outbreak of rioting and looting in the last week of November on the false suggestion on social media that some stabbings outside a school had been caused by a migrant. Though proven not be true, the incident triggered a very public row about the government’s generous immigration policy, not least in admitting 100,000 refugees from Ukraine.

The prospect of surges in uncontrolled or permissive migration is a hot button issue for political discourse across the world. More than half the members of the UN will undertake nationwide polls and elections next year. Migration is sure to be a hot button issue at the hustings.

In other words, migration, and its complex relationship to climate change – to say nothing of its role in identity politics – will have a persistent capacity for strategic shock. However, how, and why the shock comes about will be far from obvious and may frequently be based on false arguments and analysis.

It is compounded by narrow local politics – especially the politics of identity and belonging. And depends on public perception – such as the rumours fed by extreme factions in the Dublin riots in November. The twists of fact and fiction are amplified by media, especially the new social media.

This is the conclusion of Robert Kaplan, who has watched and studied first-hand the movements of African, Mediterranean, and Middle East peoples over several generations. “You can hear talk of billions on the move, in apocalyptic terms. These can be linked to conspiracy theories, which have blossomed on the internet and social media since the Covid lockdown,” he says.

Kaplan suggests that most migration in Africa and elsewhere is within regions, with relatively smaller numbers prepared to move between continents. Migration across the Mediterranean will continue, and Europe will be under pressure from the South for decades to come.

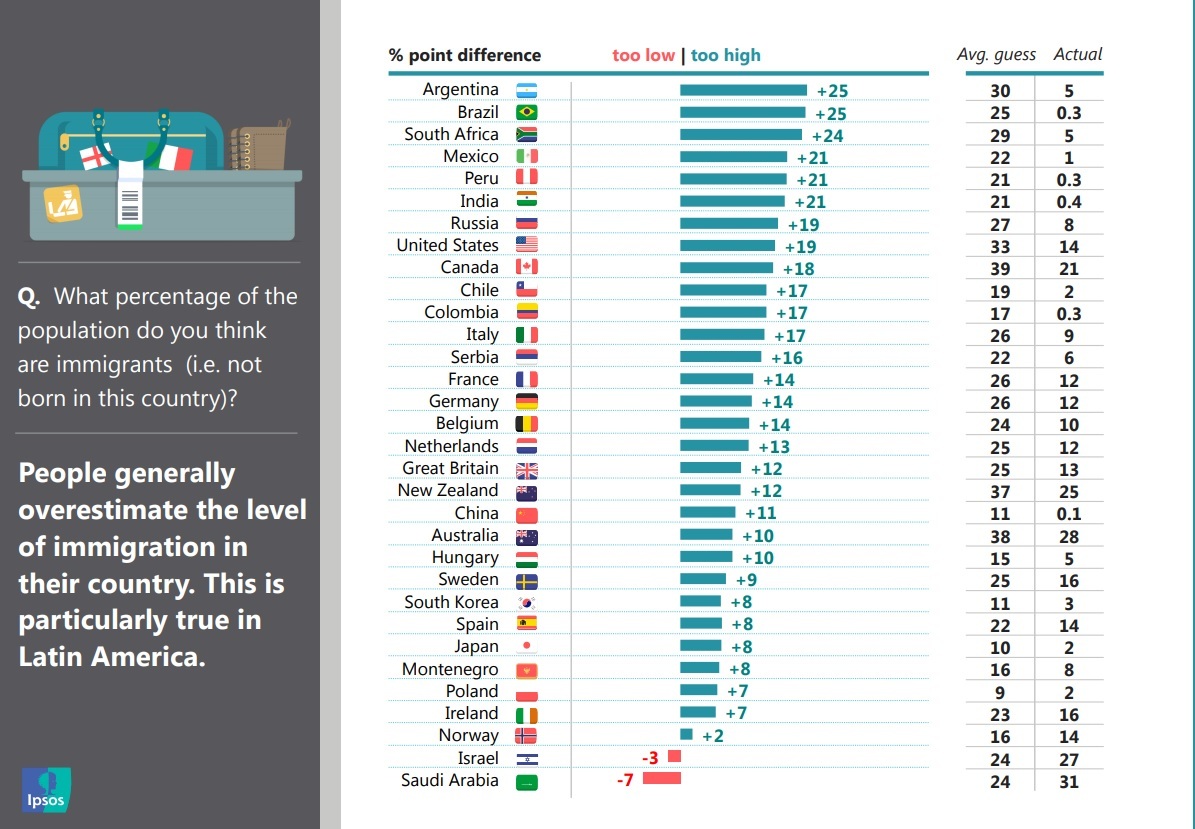

Source: Ipsos

Wars, sudden political upheaval, and rapid environmental change will continue to cause sudden shocks. The war and the changing climate, for example, are driving another chaotic flight of thousands from eastern Sudan into Darfur, fast becoming one of the most troubled centres of human misery at the close of 2023.

Conspiracy and doom-laden prognostication are fed by media, says Hein de Haas, now a professor in Amsterdam and former head of the Oxford Institute of Migration. “They like to talk in apocalyptic, biblical terms. And they love hydraulic images: waves of migrants, floods of refugees, human tsunamis.”

“Rising seas risk climate migration on ‘biblical scale’ says UN chief” ran a headline in the Washington Post on February 15, 2023. Rachel Pannett reports in the article the claim by the UNHCR that 100 million migrants had been forced to move in 2022. Accordingly, UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres is quoted as believing we are “sleepwalking to climate catastrophe.”

The changes wrought by the twists of nature and climate are compounded by the malice and incompetence of humans. Matthew Syed, a leading columnist of the London Sunday Times, has suggested that much illegal migration has been weaponised by the enemies of the democratic west. “The autocratic axis has every incentive to stoke conflict as a geopolitical weapon, knowing that desperate people displaced by war and suffering will seek out western Europe.” To avoid “the intolerable burden” of migrants in our midst, he argues for abandoning the European and UN conventions on human rights.

A week later another luminary columnist of a conservative newspaper, Tim Stanley of the Daily Telegraph, used the Dublin riots to call time on the Irish Taoiseach Leo Varadkar’s record immigration to Ireland. Commenting on a poll that 75% of Irish respondents felt their country “is taking too many” he observes: “Today one in five (Irish) residents was born abroad, an astonishing demographic change. Ireland has admitted about 100,000 Ukrainians, which is admirable, but they’ve often been housed in hotels, at considerable cost.”

The sense of outrage, and panic is palpable in such commentaries, but Hen de Haas believes they come from a mistaken understanding of where migration now sits with most communities of the West. The proportion of migrants to the rest of the world population has been constant for more than a decade – at roughly 3.6% of world population. Only a fraction of these are refugee asylum seekers. Most migration is within regions and not outside and beyond them. Sudden movements and upheavals, such as the outpouring of six million refugees from the Syrian war and the flight of the 750,000 – my deliberate underestimate — Rohingya from Myanmar, can and does cause strategic shock and upset – compounded by local politics in the destination countries. The arrival of the one million refugees from Syria and the Middle East in Germany in 2015 proved just such an example among the hosts, though it had been agreed by Angela Merkel’s government.

Migration is loaded with myths, claims Hein de Haas, and exploding them forms the structure of his new book “How Migration Works,” based on his studies at Oxford and in Amsterdam on migration, through the Institute of Migration especially. The subtitle to this intriguing essay throws down the gauntlet – “a Factful Guide to the Most Divisive Issue in Politics.” Interestingly, though published by one of the major global English language publishing houses, Viking Penguin, it has received little public attention, not least from the political arena.

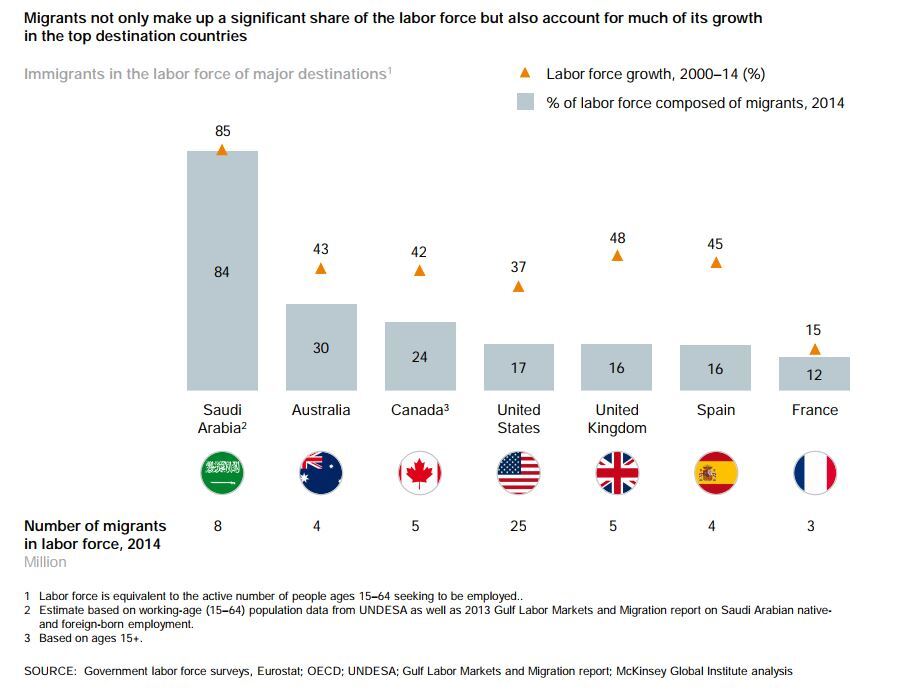

The book sharply depicts what is, and what is not, happening in global migration. It also examines the ambiguity of political attitudes, particularly those in government. Angela Merkel accepted the refugees in 2015 out of humanity, but also a pragmatic approach to resolving Germany’s demographic deficit in the working population. As Germany and many other developed nations, especially in Europe, acquires an increasingly ageing population it faces a corresponding relative decline in the working population – and this is not mitigated by automation. According to some calculation cited by Merkel’s supporters, and EU Commission analysis, Germany would require a working population of 20 million migrants to make up the shortfall over the next thirty to forty years.

Source: Government labor force surveys, Eurostat; OECD; UNDESA; Gulf Labor Markets and Migration report; McKinsey Global Institute analysis

Governments of advanced western economies like Britain, France, Germany, and the Netherlands, face a migration ‘trilemma’ of competing aims, says de Haas. A trilemma is a trio of competing propositions, in which two might align if you are lucky.

They want to appear tough on restricting migrants – to quell the ‘rising tide of foreigners’ polemic’ – but they need migrants to fulfill the shortfall in jobs. In the Netherlands there are currently 114 vacancies for every 100 jobs filled, a significant margin – and they must also appear to be abiding to norms on human rights that are compatible with a rules-based order and good governance.

The focus for most of Western European governments remains the swings and shifts of African populations, coupled with the pressures of climate change leading to desertification and destruction of farming land, particularly in the Sahel and the sub-Sahara belt. The conditions for cultivation in the south of countries like Mali and Niger are depicted brilliantly in Robert Kaplan’s latest articles and essays, based on recent travels and firsthand observation.

The worsening conditions will lead to people uprooting and moving. But this does not mean we should expect ‘tsunamis’ of migrants travelling from south of the Sahara belt to take ship to Europe. “They will move within the region. The very poor can’t travel far. To migrate long distances takes ingenuity, and money,” Kaplan told me recently. But this does not mean the transcontinental migrants will not come. They are sure to increase – though not necessarily in the numbers, the millions and billions forewarned by the anti-migration doomsayers. “With the growth of the bigger ‘middle-class’ states, Nigeria, Kenya and South Africa, the aspiring families and classes will still want to come to Europe for education and professional improvement.”

However dire the physical circumstances, Kaplan believes the poor farming communities are discovering in themselves the ingenuity to survive – to shift home a little and manage what they can get. Desertification is played down in de Haas’s magisterial, “How Migration Really Works.” Looking at the sudden environmental change in East as well as West Africa, take the north of Somalia, for example, which has become uninhabitable inside ten years. There even the al Shabab Islamists have had to up sticks and move their training camps south. In the deserts of southern Iraq, ten years ago the inhabitants would searing local dust storms about 30 days in the year. Two years ago, local shepherds and herders reported to the ICR that the storms made conditions impossible for more than 300 days a year.

Further east, the effects of the big melt of the great glaciers of the three mighty central Asian ranges, Hindu Kush, Himalaya, and Karakoram, are increasingly impacting the cycle of flooding and drought, water wars and local power struggles. This contributed to four summers of major drought in Afghanistan leading up to the rapid return to power of the Taliban in the summer of 2021. Whole areas of rural Afghanistan, desperate from the privations of the drought, appear to have turned in a matter of weeks to the Taliban as the only providers of help and justice.

Angela Merkel accepted refugees out of humanity, and a pragmatic approach to resolve Germany’s demographic deficit.

For Kaplan, the biggest question raised by the change of conditions owing to climate is Africa’s ‘Youth Bulge.’ The Bulge reaches into the Middle East and beyond – where so much of the population is under the age of 30 or even 20. In areas of the Negev desert the majority in some Bedouin villages are under 12 – in other words pre-pubescent. “Most of the youth bulge affects the sub-Sahara,” Kaplan told me. “This doesn’t mean they will surge north, though some aspiring young people will be attracted to move”, most likely to Europe first. He believes that what happens with the youth boom is an open question and will remain so for at least 60 years.

According to the World Bank the natality of Africa is 5.81 surviving children per childbearing woman. These cold statistics hide a sad truth; in many areas families of 12 children to one mother are not uncommon, and the rate of infant mortality due to disease and malnutrition is high.

Governance is one of the biggest questions for Africa and the regions impacted by climate change, environmental stress, the demographic switchback, and migration. Kaplan has depicted the waning investment in democracy – and the distance between governed and governing has driven the wave of military coups in central and sub-Saharan Africa – eight or nine in eighteen months. He fears that governance and democracy are becoming a ‘wicked problem’ in destination countries for migrants as well as the countries and regions of departure.

The population of Africa in 2022 stood at roughly 1.5 billion, about 17% of the global population of about 8.1 billion. By 2050 it is expected to be 2.5 billion and 25% of the human population; by 2100 it is anticipated to reach 40% of the world population, according to the IMF. By the end of the century the total population for the planet is anticipated to be about 11 billion. Most demographic projections assume that population growth will have plateaued by then and may even start to decrease owing to declining natality across most industrial and post-industrial nations and economies.

Today the number of migrants recorded by the UN’s IOM, the International Organisation for Migration, is 281 million. However, such statistics must be treated with care, given the varying quality of reporting bodies to the IOM.

At best these snapshots are impressionistic. Of the 281 million, only a proportion are refugees and asylum seekers. De Haas believes the proportion of migrants in the global population has been steady for decades and is unlikely to change. He says caution is due because of the confusion of language and terms in such reports. That said, the IOM’s league table of destination regions and countries for migrants is intriguing.

Europe is currently the top target destination. In 2022, 87 million migrants aimed at or are resident in the region, some 39.9% of the international migrant population. Asia comes second, with 86 million international migrants, 30.5% of the total. Next comes North America, with 59 million, or 20.9% of the total, then Africa with 25 million, 9% of the total. Oceania, where stopping the boats was first coined as a slogan, hosts 9 million migrants, 3.3% of the total.

Looking at the mélange of statistics and extrapolations, it is hard to make comparisons between the experiences of regions and continents. The United States currently hosts about 13 million undocumented and illegal, migrant workers – most vital to the economy. In the year to autumn 2023, some 2.4 million arrests were made for breaches and attempted illegal entry on the southern borders of the US. Some half-million are reported to have attempted to cross the Darien Gap between Colombia and Panama, heading eventually to the US-Mexico border in the past year. In the last two years 400,000 are reported to have fled the régime in Venezuela, heading north.

Snapshots are impressionistic. Only a proportion of migrants are refugees and asylum seekers.

Donald Trump’s project to ‘build the wall’ has had varying fortunes – but it is sure to raise a hot button issue in the US election year of 2024. Some believe that it is impossible to stop immigration by hard policies and fortified frontiers – hard though the likes of Viktor Orban and Donald Trump may try. That said, hard borders do seem effective in absolutist regimes: the border between China and North Korea seems all but impregnable.

On the other hand, thriving migration traffic clearly exists between the further reaches of China, Mongolia, and the Russian Federation. Poor farmers move into Russia as land, albeit quite marginal, becomes available for some form of cultivation with the warming of the tundra.

In China itself there appears to be large scale internal migration with the shift from the countryside to industrial city, and the displacement of villages across whole valleys and districts in the development of massive industrial, transportation network, and energy projects.

Coupled to this must be the notion of ‘circular migration’ – migrants who come for work and then go back home. It is a quite a common phenomenon between Europe and the Maghreb, as a young Tunisian barman explained to me in Ostuni, Puglia, in Italy’s south-east. The then Italian Interior Minister, Claudio Martelli, in drawing up plans to regulate Mediterranean migration into Italy termed this ‘migrazione di pendolarismo,’ or ‘commuter migration.’

Terminology can be difficult. As both Kaplan and de Haas have remarked, language on the impact of migration, its policies and potential for strategic shock, can be quite loose. A simple essay implies simple terms. The differences between migrants and migration, refugees, and asylum seekers have to be observed. It leads to imprecise categorisation. The UK and Italy, for instance, have difficulties from the backlog of asylum application processing; the system is as much a problem as the asylum seekers themselves.

In the case of the UK the current backlog is in excess of 50,000. The failures in the system should not be used as an excuse for cancelling all asylum applications, as in the Wilders electoral platform, or cancelling the UN and European conventions and dropping the non-refoulement principle proposed by the Sunday Times, opening the way to sending migrants back to regimes of torture and worse. As Hein de Haas points out the notion of a bogus asylum seeker is a fashionable myth in the current culture wars.

Perhaps a bit of retooling of some old concepts may be helpful. I offer two. The great Fernand Braudel, founder of the Annales history school, coined the term la longue durée. This is the portmanteau concept for the long trends that shape human destiny – the mountains, the seas, the village, the town, and the trade routes by land and sea – which he lays out most eloquently in his masterwork “The Mediterranean in the Age of Philip II.” We have seen an acceleration of this process in our own time with the majority of humans now urbanised, and the rise of the megacities.

Today we are going through what we should see as another version of the longue durée, a new and at times unpredictable reshaping of society and politics against the backdrop of changing climate and environment. These will condition the capacity of apprehensions and misapprehensions about migration and its capacity to cause strategic shock.

The second term should be ‘smart’ migration policy. Migration is with us and will continue to be so for the rich developed nations and economies of the Global North. Nearly all are facing a demographic deficit in the available working population, including the United States. EU advisers think that some 50 million migrant workers will be needed across EU Europe in the next 40 years.

The UK is challenged on two counts, according to de Haas. “The UK, Netherlands, and the US have the most open labour markets, and they draw in migrant workers because they need them. It is part of the gig economy.” The UK has a rapidly ageing population, not as much as Japan and Italy, maybe, but a natality rate of around 1.69 per mother or potential mother in England in 2022. This leaves a sizeable replacement gap.

Source: James Stout Media

The UK, especially since Brexit, relies on informal, undocumented labour in key sectors – seasonal horticulture and agriculture, much transportation, and the construction industry. Many of them would be deemed illegal immigrants. More migrant workers will be required for the care sector and for staff at all levels in the National Health Service. “The inability of the National Health Service to recruit and train medical and nursing staff in Britain itself is really concerning,” says Professor de Haas. Pledges by the leading parties at Westminster to restrict migration, demanding higher qualifying incomes for aspirant migrants, and restricting partners of students, threaten critical damage to public services.

Migration is and will be the source of strategic shock, but not in the terms generally proclaimed in the arenas of politics and the more rancid polemicist media and press. The shock happens with sudden change and surges in populations disrupted by war, oppression, and disaster, and the new longue durée in climate and environmental shift.

For Britain the impact of an ageing population, the demographic deficit, and the requirements of the growing complexity in welfare, care of the elderly and medicine at all levels is yet to be felt. Without some adjustment to smart migration policy, it could be a strategic shock indeed.

Robert Fox is Defence Correspondent for the London Evening Standard and author of The Inner Sea: The Mediterranean and Its People.