Winter 2022

Asia Caught in Between

The countries of Asia are old hands at being ‘in between’. In fact, this vast continent we now term the Indo-Pacific, where attitudes have been shaped by legacies of European colonialism, has a fair claim to have invented the idea’s Cold War form at the Bandung Conference in Indonesia in 1955 and with the Non-Aligned Movement that grew out of it. Today, however, while being in-between veterans can be profitable, it is also uncomfortable. The region’s core task is to deter the superpowers from bullying them into making choices. That task is getting harder, by the day.

This is as true of those Asian countries that have been in security alliances with the United States ever since 1945 – Japan and South Korea – as it is of the two regional giants, India and Indonesia, which made non-alignment something of an art form during the Cold War, or indeed of the many smaller countries in South-East Asia and around the Indian Ocean. Even distant Australia and New Zealand, though clear about which camp they belong to, are keen to deter the powers from forcing the choice on others.

For this whole region, the profits of in-betweening have long been clear. China is the largest trading partner of virtually every country, but the United States is generally the second largest: in 2021 China took 20% of Indonesia’s exports and the US 14%; for South Korea the figures were 25% and 14%; for Vietnam the order is reversed, with the US taking 23% of exports and China 15%; for India the US and China regularly swap places with each other as top trading partners.

More recently, as China has become more self-sufficient economically and less dependent on being part of a pan-Asian supply-and-assembly network, it has become profitable to be an alternative investment destination or materials supplier to China. Vietnam was long the favoured country for Japanese firms pursuing a China-plus strategy of risk-spreading. Now Indonesia is benefiting from the widespread desire to reduce dependence on China as a source of “green” raw materials for batteries and other renewable energy devices, while successfully capturing processing of those materials too.

Go to the far western edges of Asia and you find the ultimate look-all-ways economies: the Gulf States and Saudi Arabia. Dependent as they are on American technology and military bases to keep them safe, the Arab oil-producers are currently in an in-betweeners’ heyday, with high energy prices flooding their vaults with petrodollars, with customers from the east vying as much for their business as customers from the west, and with abundant funds to spend on new cities and infrastructure that are luring in contractors and financiers from Japan, China and South Korea just as much as from Europe or North America. The Arabs know a moment of strategic leverage when they see it.

Yet they, sitting on the extremity of the region but also surrounded by conflict and insecurity, epitomise the in-betweeners’ dilemma as much as their opportunities. The last thing the Arab states want is to antagonise or drive out the Americans. Where else would they get their F35s? Where else would their princelings go to school or college? But the second last thing they want is to be under the Americans’ thumb.

Out in the heart of East Asia, the western Pacific and the South China Sea, the dilemma is geographical far more than ideological. Most of the region has worked hard ever since the end of the Vietnam war in 1975 to keep the US involved as a stabilising force – most recently, few harder than Vietnam itself, especially since that country’s 1979 border war with China.

The Philippines pushed the Americans out of the huge Subic Bay base in 1992, but like other members of the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) have still welcomed a big US presence in the western Pacific. That welcome has become even warmer during the past half century of China’s rise as an economic and military superpower.

The implications of that rise have become clearer by the decade, but especially so this year.

Most countries were naturally disconcerted by the Joint Statement between China and Russia that was released on February 4th. While being less bothered by its explicit anti-West theme, Indo-Pacific nations were nevertheless shaken by the statement’s implicit theme, made real by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24th, that this pair of superpowers were advocating multilateralism, non-violence and a rules-based order for smaller fry but not for them.

Few, if any, then saw the Global Security Initiative announced by China’s President Xi Jinping in April as likely to amount to anything meaningful, still less reassuring. The littoral nations around the South China Sea have had too long an experience of grappling impotently with China’s “nine-dash line” staking its UNCLOS-busting claim to the whole area to take seriously any notion of shared security. They see the Chinese airfields and other bases built on reclaimed reefs in the South China Sea as an intimidation, not a protection. So, when Prime Minister Fumio Kishida of Japan said at the IISS Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore in June 2022 that “Ukraine today may be East Asia tomorrow”, all the countries present knew what he meant and few demurred from his judgement.

Yet the historic stabiliser, the United States, is now rattling nerves across the Indo-Pacific at least as much as China is. It is doing so in two main ways, while irritating and disappointing the region at the same time.

Most obviously, it is rattling nerves by not just warning about a potential Chinese invasion of Taiwan but by taking actions that many in East and South-East Asia, at least, fear might make an invasion likelier. The high-profile visit to Taipei by the Speaker of the House of Representatives, Nancy Pelosi, in August was a notable example, but so too had been gestures by President Donald Trump during his 2017–21 White House term towards treating Taiwan’s political leaders as if they were recognised heads of government.

The chance that a future US administration might actively or inadvertently encourage Taiwan to declare its formal independence is perceived in the region to be rising, and such a declaration would be expected to be a red line, a casus

belli, for China. It would bring forth the likelihood that the Chinese leadership would henceforth decide that the domestic political risks of not invading or coercing Taiwan into reunification had come to exceed the always high risks of failing in such an intervention.

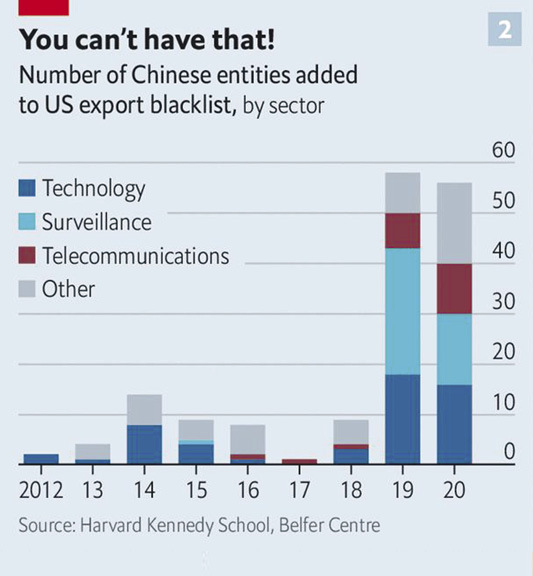

The second nerve-rattler has been the escalation this year by the US of its economic warfare against China in the form of bans on the transfer of advanced semiconductors, components and the equipment needed to make them. This went far further in challenging China’s technological development than had the trade tariffs imposed by Trump or his administration’s efforts to exclude the Huawei telecoms firm from western communications networks.

The export controls on semiconductors are designed to retard Chinese development of the most advanced forms of computing, which promise to become a critical part of the military balance. In some ways, that might be expected to please some of China’s more nervous neighbours, since it should push back the date when China’s huge military will become overwhelmingly dominant. But it is uncomfortable because it forces choices on companies and countries. Every element of the semiconductor trade involves an East and South-East Asian supply chain.

Source: Semiconductor Industry Association

The countries that form the principal links in that supply chain – chiefly, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, but also Malaysia, Singapore and others – gripe that the US made a show of consultation on its semiconductor export controls, but then dropped the talks and went ahead regardless. The clarity and resoluteness of US strategy is recognised and even admired in Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, but companies and governments are acutely conscious of the risk, perhaps likelihood, of now being entangled by the long extraterritorial arm of American law.

If this form of national security-based decoupling were to be matched by a positive embrace by a generous and far-sighted US economic policy towards the region, that nervousness might be somewhat calmed. But these are protectionist times in the US Congress and Joe Biden’s White House too is pursuing ‘make-in-America’ strategies in its infrastructure and climate-change policies.

The country’s big East Asian trading partners are miffed as are Europeans by America’s turn away not just from globalisation but even from regional free trade. The ‘Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity’ (IPEF) that the US launched in May 2022 is seen as being about as content-free and meaningless as China’s Global Security Initiative. And compared with China’s infrastructure-building Belt and Road Initiative, the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment announced by Joe Biden and the other G7 leaders in June looks aspirational rather than operational. The BRI is smaller than it once was, but at least it brings real money.

So what are the Indo-Pacific’s in-betweeners to do? Geography makes China both disconcerting and unignorable. The United States is welcomed as the only stabiliser or protector available, and is trusted much more widely than is China, but it too is making lives uncomfortable. The attitude encapsulated by a quip from an Indian Congress Party politician in the 1990s, Jairam Ramesh, remains typical: the spirit is “Yankee Go Home – and take me with you”. But cultural links and a preference for a liberal power can only go so far in countering geographical realities.

International relations theorists talk of “hedging strategies” for countries caught in the middle like this, but the reality is more complex than that anodyne phrase implies. The strategies followed by Indo-Pacific nations take a myriad form, many of them overlapping, consisting of a mixture of national policies, “minilateral” or multilateral efforts made with others, and bilateral strategies towards the two principal superpowers, China and the US. Broadly, they can be summarised under four main headings:

Source: Harvard Kennedy School, Belfer Centre

Alignment with all.

Epitomised by India, this modern variant of non-alignment involves being a member of virtually any regional grouping going, even when in some respects they might seem to contradict one another. Thus, India is a member of the Quad, the gathering of Japan, the US, Australia and India that Japan originally and the US more latterly envisaged might develop into a security and intelligence organisation, but so far remains thinner than that. It initially remained thin because Australia was reluctant to offend China. Now it is thin because India wants simultaneously to be a member of the BRICS grouping – Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa – as well as the Shanghai Co-operation Organisation. India’s aspiration is to be a hub or camp all of its own, perhaps, but for the moment its strategy is to seek the best of all worlds, while edging slowly away from Russian defence technology and towards American. Yet while India is the most extreme case of all-alignment, the proliferation of minilateral groupings suggests that other countries share its aim of talking to everyone but being subservient to no one.

Security enhancement as a deterrent.

Meanwhile old-fashioned defence build-ups are an equally common response. Japan is the outstanding case, now pledging to increase defence spending to the NATO standard of 2% of GDP by 2027, albeit in part by agglomerating some existing spending under the umbrella of defence (by NATO measures, Japan’s current defence total is about 1.25% of GDP, rather than the 1% officially claimed). But others too are building up their forces and, just as crucially, stepping up joint military exercises with other Asian countries and, in many cases, the United States. A prime example is the joint exercise hosted annually by Indonesia known as “Garuda Shield”. This began in 2007 as a collaboration between the US and Indonesia, but next year is expected to include India, Australia, Japan, Malaysia, Brunei and others. The aim of this and other such collaborations is a mixture of deterrence and improving operational capabilities.

Diversification not decoupling.

If any region can be considered as the heartland of modern globalisation, it is East Asia, though arguably the wider Indo-Pacific too. While the notion of “decoupling” may be commonly discussed in Beijing or Washington, the preferred and encouraged theme in the region is one of diversification. Supply chains have anyway evolved away from the China-centric model that was common in the 1990s and 2000s, but championing the diversification of suppliers and production locations has become common especially in South-East Asia. There is no appetite for regionalisation, for the whole region is too outward-looking for that to make economic or political sense. The North American notion of “friend-shoring” sounds hollow to East Asians, who may consider themselves friends but have no intention of making the friendship exclusive. Those in the region that do not have democracies – notably Thailand and Vietnam, but also many others – also resent the American idea that the world can be divided between autocracies and democracies. Nonetheless, business is there to be done. The region’s economies are large enough to support, and benefit from, a more complex matrix of supply chains with countries promoting themselves as diversification locations, especially for big American and Japanese firms.

Agency not autonomy.

In the Indo-Pacific, probably only North Korea thinks it can or should be autonomous, whether in security or economics. But all, including those tied most closely to the United States such as Japan and South Korea, are aiming to increase the weight and influence of their own security and economic policies so as to make them more important – and less taken for granted – to both the US and China. Defence build-ups are one important element of this, but so are regional trade organisations, most notably the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, the CPTPP, which Japan, Australia and Indonesia rescued after the US dumped it. This 11-country organisation has become the most substantive rule-making body in the region for trade and investment. This gives Japan and the other leading countries more agency. No wonder the United Kingdom is keen to join it.

There is no easy way to navigate these turbulent times as an inbetweener, right on the front lines between China and the United States, and with Taiwan right in your midst. As but one example of that, consider this. China’s two aircraft carriers have so far confined their sailings to Chinese or international waters. But suppose one of them, likely the newly launched and indigenously designed Fujian, wanted to make a port visit so as to project power, just as American or European carriers do. Where might it visit first?

The likeliest answer is Singapore, whose port facilities are frequently used by the US Navy but which are officially open to all. Smaller Chinese naval vessels have already paid calls there. And, unless it was a moment of high international tension, Singapore would not say no. Singapore can be considered a Chinese-led multi-ethnic society, but it is also one with strong westernised characteristics, one which knows it does not wish to be bossed around by China. But it is firmly in-between. And that is where it wants to stay.

Bill Emmott is Senior Adviser on Geopolitics at Montrose Associates. He was Editor-in-Chief of The Economist for thirteen years and former Chair of the Japan Society and the International Institute for Strategic Studies. He is author of Rivals: How the Power Struggle Between China, India, and Japan Will Shape Our Next Decade and his most recent book is Japan’s Far More Female Future, published in Japanese by Nikkei in July 2019 and in English by Oxford University Press in 2020, author of Deterrence, Diplomacy and the Risk of Conflict Over Taiwan (2024).