Winter 2022

Europe: Sidelined

Before this year‘s G20 meeting started, the leaders representing the old and the new superpowers tested the waters of their increasingly chilly relationship. Despite a long list of controversies, they decided to put forward jointly an important message: a clear condemnation of Putin’s nuclear threats in his war of aggression against Ukraine. Thereby, both underscored their resolve in preserving global stability. To avoid the risk of unwanted escalation, they decided to manage their strategic disagreements by a network of consultations at working level. A new cold war, they insisted, did not lie in their respective interests.

The contest for global geopolitical and geoeconomic power has started and will intensify.

But the differences remained obvious. While Biden stressed that the US would vigorously compete with China being prepared to set limits and clear rules to the competition, Xi denied that this was a competition, and instead stressed that China has the right to pursue its ambitions worldwide.

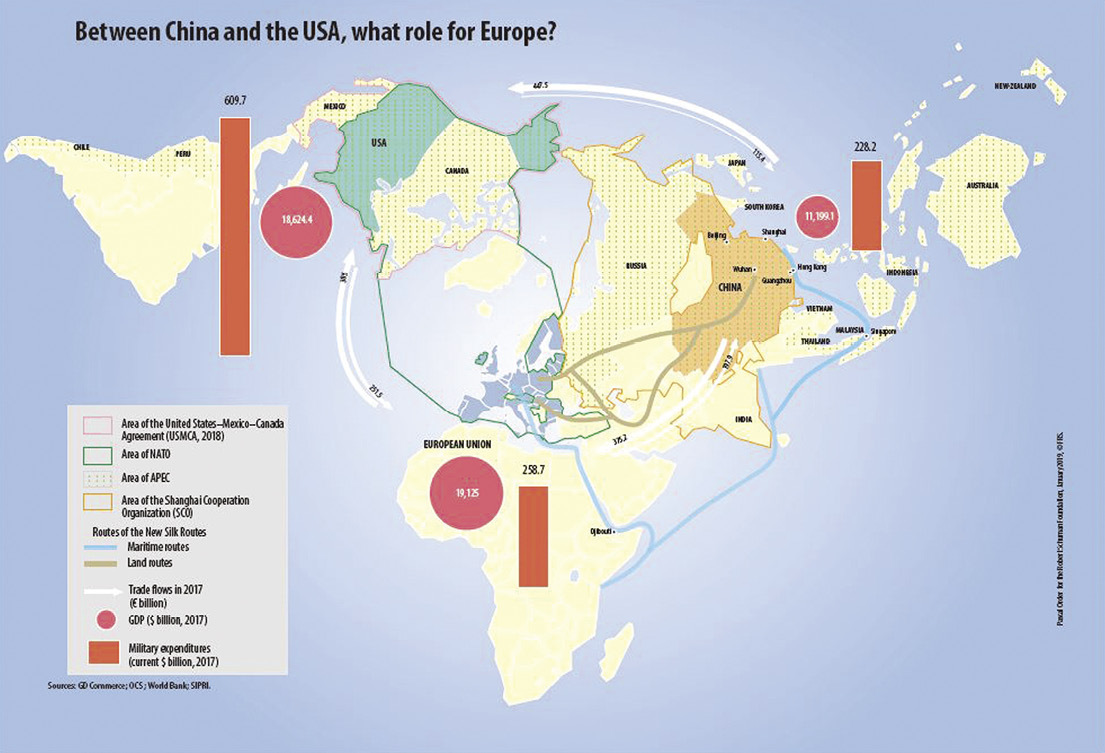

The G20 meeting that followed, clearly dominated by that bilateral encounter, reflected four significant trends: 1) The multipolar system predicted by many will be a bipolar one in the medium-term perspective; only the protagonists have changed; 2) Russia, and in particular Putin, is more isolated than ever; the fact that the final G20 declaration calls a spade a spade (i.e. the Ukrainian war a war) and that most G20 members condemned the war with unmistakable clarity, is significant; 3) The countries of the global south do not want to be drawn into a new cold war, this time between US and China; they do not want to take sides for one or the other; but they do want a multilateral system which safeguards their interests; therefore an Alliance of liberal democracies, as proposed by Washington and some Europeans, will be a no-go; and 4) Europe, despite being the second largest economic power in the world, was symbolically invited to take a back-seat — like the other G20 members. It is far from being a global actor.

Bali has demonstrated that the post-Covid world is changing rapidly. There will be no return to the old global order

However, we cannot yet identify the direction that the dramatic changes will take. Rhetoric in Washington and Beijing reflects the logic of unavoidable conflict between the geopolitical and geoeconomic interests of the superpowers; but it is totally unclear if one or both contenders are ready to cross the red lines of the other, and if the so-called Thucydides trap is avoidable or not. And what that would mean for Europe and the rest of the world, the G20 and beyond, all of whom are bystanders to this power gambit.

America – democracy in decline.

The US is weakened by deep ideological conflicts in its society. Since the events of January 6, 2021, some even see democracy at stake. Congress is split over every possible topic, except for one bipartisan consensus: China is seen as the greatest threat to America’s supremacy.

Since Chinese President Xi Jinping proclaimed his goal to lead China to global technological leadership by 2049, Washington is poised to prevent China’s further geoeconomic and geopolitical rise — at whatever cost. If necessary by using extraterritorial measures directed even against allies and partners in Europe. Washington’s Inflation Reduction Act is only the latest proof that rising American protectionism will not spare European business. This is not just a Trump legacy. The shift started with the pivot to Asia by Obama, it has become a driver of Biden’s Pacific agenda and will no doubt be continued by whoever succeeds in Washington after the next Presidential contest. America first has put an end to the conviction that global interdependence and division of labour are the prime guarantees for stability and prosperity.

Neither systemic rivalry nor the protection of American hegemony in the Pacific are the prime reasons why Washington is throwing down the gauntlet to Beijing. It is the American resolve to preserve its global economic supremacy. This objective requires the US to gain the upper hand in the competition over data controlling finance, defense, energy, industrial production and other strategic sectors. Only by holding control, many experts believe, will the US be capable to preserve its economic power – a power which is held together by enormous external debts. The supremacy of the US dollar remains a precondition for its geopolitical superpower status.

China – rising autocracy

China has developed a stronger ideological and nationalist agenda under Xi Jinping than under his predecessors.

Domestically, stability has highest priority. Xi is convinced that stability can only be safeguarded by the Communist Party. As Secretary-General of the Communist Party, he has concentrated more power in his hands than anybody since Chairman Mao. Digital supervisory systems like the social credit system or repressive measures in Xinjiang or Hongkong are subordinate to this objective. Rising criticism from abroad is a quantité negligeable for the Communist Party leadership.

The Chinese population still accepts the social contract which has existed for many years: People can get rich in any way they want but, in return, they will not stick their noses in politics. They respect uncontested leadership by the Communist Party as long as they participate in the country‘s growth and development. But this deal seems to be eroding gradually. The fury over the rigid Covid lock-down policy by Xi Jinping has started to turn frustration into protest in many parts of China. The slow-down of economic growth due to the global recession caused by the war in Ukraine is robbing hundreds of millions of a chance of social mobility. Thousands of well-trained young people cannot find jobs for the first time. And demographic change, the greatest challenge to future economic growth, will hit China for the first time this year. All of these factors create stress for the legitimacy of the Communist leadership. At the moment, there is no prospect for régime change, but the multiple crises are the seed for distrust with the ruling elite. There is a fissure of credibility which the leadership has to fix.

A sober view at the emerging global governance may help.

Reunification of Taiwan with mainland China, seen by most Chinese as a legitimate objective, could be the nationalist card played to distract the population from the economic downturn. Defending the one China claim remains a consensus in the Middle Kingdom. But an invasion of the island is a double-edged sword. It would only have a stabilizing effect if it would increase China’s economic performance by incorporating the economic powerhouse of Taiwan. A destruction of the Taiwanese industry by military force would run contrary to that interest. Furthermore, an incalculable reaction by the US and its Western allies would have serious geopolitical and economic implications for China. For those reasons, and contrary to American voices, this worst-case scenario seems unlikely in the medium-term perspective. But there are multiple options China could choose with the objective to put more pressure on Taipei. A sea blockade or cyber attacks are but two of them.

Nevertheless, the rhetorical option by President Xi to achieve reunification, if necessary by force, has been perceived by the West as a change of parameters. This alarming threat perception has certainly been triggered by Putin’s brutal war against Ukraine, rather than by a significant change of parameters in the South China Sea – which has been an arena for Chinese demonstrations of power for many years. China’s quest for unification is as old as the PRC, and even military action by Beijing against Taiwan has always been an option in case of a change of the status-quo from outside, i.e. a proactive policy towards independence of the island.

The harsh reactions in particular in America, but also in Europe, reflect the increasing image of China as a foe. The visit of Nancy Pelosi, Speaker of the US House of Representatives, to Taipei in August 2022 was, therefore, perceived as an act of provocation, which Beijing answered by a similarly provocative, oversized military manoevre. But even if an intentional invasion of the island is rather improbable, this symbolic encounter has demonstrated the explosive nature of this conflict. China will not give up her claim, if only for obvious nationalistic reasons; and the US will continue its policy of strategic ambiguity, if only as a symbol of its reliability for the security of its Asian partners. Taiwan must therefore be at the center of what onetime Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd has called MSC, a process of managed strategic competition. The risk of unwanted escalation must be significantly reduced.

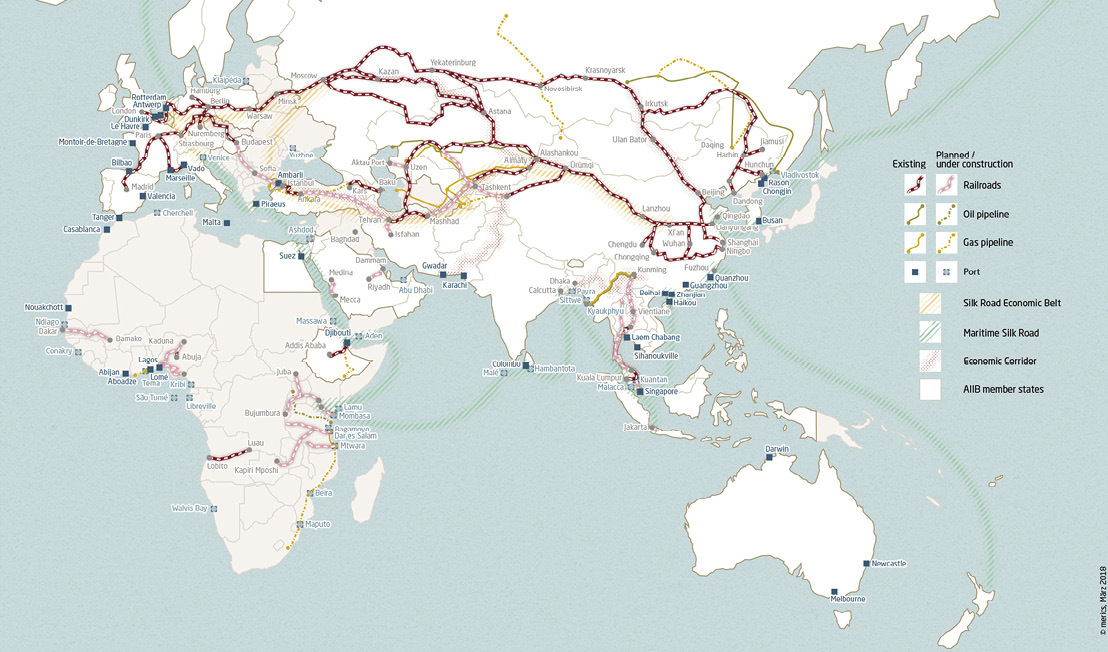

Source: Merics.org

Beijing’s foreign and foreign economic policies, in particular the concept of the Belt & Road Initiative (BRI), are perceived by many in the West as increasingly aggressive, signaling a shift towards hegemonic objectives. It is, however, more likely that the BRI pursues geoeconomic rather than geopolitical objectives. It is serving China’s domestic market which cannot generate sufficient growth anymore. And growth is the precondition for stability. Therefore, China pursues a tough policy of bilateral agreements ensuring imports of energy and raw materials, as well as creating new markets in Central Asia, Africa and Latin America. Such strategies are deemed necessary to reduce China’s enormous dependency on the US market. The increased role of the renminbi in global financial markets is part of this strategic approach.

Geopolitically, China’s strategy in dealing with Central Asia, Africa or Latin America, even less Europe, has not aimed at régime change or the transformation of the political system of partner countries. But, of course, its interest has been and continues to be to diminish western and, in particular, American influence in these societies. As long as China profits economically from such partnerships, the famous Deng Xiaoping saying “It doesn’t matter if the cat is black or white as long as it catches mice” still stands for Chinese pragmatism. Even under the more ideological reign of Xi Jinping this has not changed dramatically — although the perception in the West is the opposite.

During the past decade, China has suffered from a dramatic loss of trust across all Western societies. Besides gross violations of human rights against the Uighur minority in Xinjiang, the limitation of freedoms in Hong Kong is perceived as a clear breach of the principle one country, two systems which Beijing has agreed to observe until 2047.

However, the most dramatic reason for the mounting distrust is Beijing’s ambiguous position towards Putin’s war of aggression in Ukraine. Only days before the beginning of the Russian invasion, Xi and Putin signed a statement proclaiming no limits to Sino-Russian cooperation. It was perceived as an alliance directed against the Western concept of liberal democracy. No doubt, Beijing misjudged Putin’s strategic and military potential. It fell into the trap of Putin’s narrative that the war was a result of NATO’s aggressive strategy to destroy Russia, and that it would be over swiftly. A successful war by Russia would have been in Beijing’s interest to weaken transatlantic cooperation, to split US and Europe, and to keep America’s attention away from China. This was a serious error of judgement. Beijing has refrained from openly supporting Moscow, both militarily and economically. It has remained neutral in voting on UN resolutions condemning this flagrant breach of international law, like the other BRICS governments. But there is a difference: China is the only global player with the leverage to convince Putin to end to this brutal war. But Beijing has remained passive. It has missed a historic chance to act as a responsible stakeholder. The joint warning to Putin in Bali not to use nuclear weapons was the minimum necessary to save face in a situation characterized by the almost global opposition to Putin’s war.

The competition between America and China for geopolitical and economical supremacy is bound to increase in the decades to come. None of the other actors will be on a level-playing field with them, at least not in the medium-term.

Europe – global would-be player

Europe’s role in this complex scenario could be that of a bridge builder. Europe could be an important influencer. It could help refurbishing the old global order as it is more trusted by many countries of the global south than either superpower. It could be the architect of a rules-based international system fit for the 21st century, given its success in building the most important and still sustainable regional system, the European Union.

It could. But Europe is weakened internally, and without clear strategy externally. It lacks confidence as well as the means and political will to make a difference.

Europe’s table silver, its most valuable asset, is its firm rule-of-law basis. It is the backbone of its liberal democracies, ensuring the balance between individual freedoms and social justice. Two generations have been able to enjoy peace, stability and prosperity thanks to this rules-based framework. It is of the greatest concern that at the moment this value base is challenged from inside the EU, as well as from outside by Russia. Not only Poland and Hungary have serious deficits regarding democracy and basic rights. Newly elected governments in Italy, Sweden and elsewhere are proof that right-wing populist movements have become a serious phenomenon in many European societies. The nation state is back in business, and the vision of a more autonomous Europe, a union with growing sovereignty over a common space of freedom, security and rule-of-law, is put on the backburner. Brexit was the peak of this development.

The international credibility of the European Union is at stake. If we cannot ensure a high standard of human rights in our own societies, it is extremely difficult to advocate rights in China or other Asian or African societies. The same is true for double standards. Human rights violations in Guantanamo have to be tackled as rigorously as labour camps in Xinjiang or maltreatment of migrant workers in Qatar. Europe has to do its homework.

Europe’s weakest point in gaining global leverage is its lack of military capabilities, its inability to safeguard its own security, its lack of political will to develop a European security and defence identity.

The EU must increase significantly its own defense capabilities, it must minimize its security dependence on America. It is true: The solidarity shown by European governments in the defense of Ukraine against Putin’s war of aggression was impressive. It was, without doubt, unexpected — for Putin, for China, for many Europeans themselves. But a sober look at the military situation shows that Ukraine would have been lost without quick and substantive American military assistance. European support with weapons, ammunition and logistics has been serious, but was insufficient and much too slow to prevent a successful invasion by Russian troops.

Without military power, European diplomacy is lacking an important back-up. Europe has been commissioned to take a global back seat due to its strategic irrelevance.

This analysis is not new, of course, but it has become even more serious after Brexit. There is no doubt that Europe must undertake a substantial turnaround given the revolutionary changes in the international system. And time is running out. In three-and-a-half years, Macron’s time in office will come to an end. It is unclear what will follow in France. The German-French relationship, once the motor of European integration, is stuttering and has to be revitalized. Without delay. Berlin must take a lead, together with Paris, to transform the EU into a union of common security and defense.

A promising start has been made by the decision of the red-green-yellow Ampel coalition in Berlin to invest an impressive €100 billion into the modernization of the Bundeswehr and to scale up its defense budget by more than the 2% increase a year, agreed to by all NATO partners. But decisions have to be followed up by action. Zeitenwende, the German slogan for turnaround, requires the speedy implementation of concrete defense projects. There is ample reason to doubt that this will happen.

Source: Robert-schuman.eu

And other EU partners have to be brought on deck. We need a critical number of European governments to achieve this turnaround successfully. Europe is able to combine forces and become a serious strategic player if it undertakes the necessary structural reforms. The piecemeal approach favored by European governments in the past needs to be replaced by a new vision of Europe’s place in the world. Europe as bridge builder, as an architect of a sustainable rules-based global order.

This vision needs to be crafted into a new constitutional framework. We need a serious start on a discourse about a new constitutional basis immediately. That is difficult in times of blooming nationalism, but there is no alternative.

A first step could be the elaboration of a joint common European security strategy. Europe must jointly generate the political will to develop a leverage of its own, to successfully participate in global competition, in geoeconomic, geopolitical, also geostrategic processes. This process of strategic thinking requires a non-ideological, interest-based approach. How can we best safeguard our European citizen’s interests? How do we ensure a sensible balance between our European values and interests, between human rights, climate protection and jobs? How could European sovereign autonomy be developed without falling into the trap of unrealistic concepts of European big power ambition or of levelling down important frameworks of historic partnerships and alliances?

No doubt, the transatlantic partnership will remain an essential alliance, irrespective of partially diverging interests. There will be no equidistance between Washington and Beijing. But Europe must realize that the US has shifted its interest into the Pacific and its geopolitical and geoeconomic competition with China. It ought to understand that the transatlantic renaissance which many are cherishing at the moment could be of short duration. It is rather to be expected that the America first spirit will reemerge with the next American President, no matter which of the two parties she or he will represent. China will be the focal point of American strategic thinking. Europe must act according to the uncomfortable reality that although it shares more common values with America than with most other regions in the world, our values are not identical; even less our interests, in particular our economic interests. Europe, for instance, needs the global market, and therefore a rules-based multilateral order. This is much less true for the US.

Like the US, a more powerful and assertive China will continue to pursue its interests rigorously. It will try to establish economic and political dependencies creating leverage. Not decoupling from China is a rational option, as is the rational diversification of our economic engagement, in particular in areas of imports of rare raw materials, and also sensitive infrastructure. Europe must prepare itself for harsh strategic competition in all innovative sectors. Data protection and control of sensitive data will be two sides of the same coin. Europe should be more self-confident in accepting competition with China, economically and politically. European companies are highly innovative, and just as China is profiting from them so Europe can profit from the creative power of Chinese companies.

A European strategy on China could, therefore, be a first important step in defining the way forward towards more European autonomy.

During the past three decades, Europe has profited from China developing into the second largest economy in the world and by far the largest marketplace for European companies. Now we must realize that the Middle Kingdom is aspiring to take over the place it once possessed in the middle of the 19th century. Xi Jingping calls this the Chinese Dream. Europe’s response is partly irritation and partly rejection. Overnight, China is regarded not just as a partner and competitor, but a systemic rival as well. As if China hasn’t been all of that for a long time. The difference, of course, is that China has emerged as a superpower.

It will be important to define what this strategic triangle of partner-competitor-rival will mean in practice.

The Ampel government in Berlin has started to elaborate a China strategy intended to offer clarification. Concrete areas of obvious partnership like climate change or the fight against new pandemics will have to be leveled out with clear rules-of-the-road for business competition. Reciprocity has been a claim for years, but has never been implemented by European laws. Dependency is not a one-way avenue, but is reciprocal. That needs to be brought into the equation. Systemic rivalry remains a political slogan, unless it is clearly defined by spelling out red lines and clear consequences should the red lines be crossed. China is not trying to change our political systems in Europe. But how should Europe react in cases of flagrant violations of international law, in particular of human rights, domestically, regionally and globally? What is Europe willing and capable of doing in the case of such violations? Where are our red lines, and what are we willing and capable of doing if China crosses such red lines?

There ought to be concern that a national strategy, which is always the product of lengthy in-fights and compromises between various players within government, will not contribute to paving the way for a joint European strategy. What we need are not 27 national strategies, but a well-crafted and workable European one. The German China strategy could be beneficial if it refrains from attempting to solve all complex issues at stake, but rather concentrates on a few key points of prime relevance. Unfortunately, the opposite seems to be the outcome in Berlin — at least if one takes seriously leaks to the German media reporting that an elaborate compendium of detailed cases is in preparation. And that the draft strategies in different ministries are in part contradictory.

Business as usual is unacceptable for the EU, and continued status-quo thinking is damaging to European interests. Europe must play an active role in preventing a cold war between the US and China, or in cooperating with all regions in the global south irrespective of a cold peace between the two giants. But this role has to be defined by the EU as a whole. National attempts of going alone are detrimental to European interests. Joint French-German leadership is necessary.

If the EU are unable to agree on necessary strategies and structural reforms at the level of the 27 nation states, the next level of integration should be realized by an avant-garde of European governments ready and willing to move forward. Waiting for the slowest common denominator has long been the European way forward, but there is no more time to continue this meticulous consensus building. Majority vote also on strategic security issues is overdue. But even concepts like core Europe should not be a taboo but should be serious options in the discourse on transition — as long as the doors for the EU member States staying behind remain open to join whenever they see fit to enter the train.

A strong, self-confident and capable Europe may even be an incentive for other European countries to join the Union. It could, and hopefully would, also open new perspectives for the people of the United Kingdom to end their chosen isolation and becoming once more an integral, valuable and respected partner in the European Union.

Michael Schaefer worked for 35 years in the German Foreign Service, including five years as Political Director in Berlin. He was Ambassador to the People’s Republic of China (2007−2013) and Chairman, BMW Foundation (2014–2020). He is a member of the Montrose advisory board.