Winter 2022

The Pressures Toward Decoupling, and How to Manage Them

At the end of November, the world had a true 2022 moment, when Apple reported that there the new iPhone 14 (already a favourite on many Christmas wish lists) is likely to be delayed – because of worker walkouts at Foxconn’s gigantic factory in the Chinese city of Zhengzhou. The worker uproar, news media reported, was likely to cause a 6 million shortfall of the gadget. But the walkouts were not about Foxconn: they were a protest against China’s draconian zero-Covid policy, which has triggered repeated lockdowns across the country ever since Covid-19 first appeared in Wuhan. Christmas faced disharmony in millions of families because Apple, like countless other companies, has over the past three decades moved large parts of its manufacturing to China. But companies that have spent the past three decades expanding abroad are now encountering forces even more powerful than viruses and worker protests. Geopolitical confrontation is forcing businesses to reconsider what it means to be a globalised enterprise – including which countries they can consider safe enough for business. The most adaptable ones will survive and perhaps even thrive.

In early December, Apple told its suppliers that it wants to shift production from China to other Asian countries, especially India and Vietnam – and then it announced that it will start making microchips in the United States, the first time in a decade. ‘Thanks to the hard work of so many people, these chips can be proudly stamped Made in America,’ the tech giant’s CEO, Tim Cook, said when announcing that it will work with TSMC, a Taiwanese company that dominates global chip production, to move chip manufacturing to the United States. The decisions were not prompted by the walkouts at the Foxconn plant, though the announcement’s timing was fortuitous. Like all companies operating in China, Apple and Foxconn have seen their operations disrupted by Beijing’s zero-Covid policy. But Apple’s executives are also acutely aware that business in China has changed in the past decade. Today Xi Jinping’s régime seems intent on imposing its will on domestic companies, international companies and foreign governments alike, and it does so by targeting individual companies. Not even China’s own corporate giants are safe. Jack Ma, China’s most famous entrepreneur, has seen his tech empire smashed by the authorities and now appears to have decamped for Tokyo.

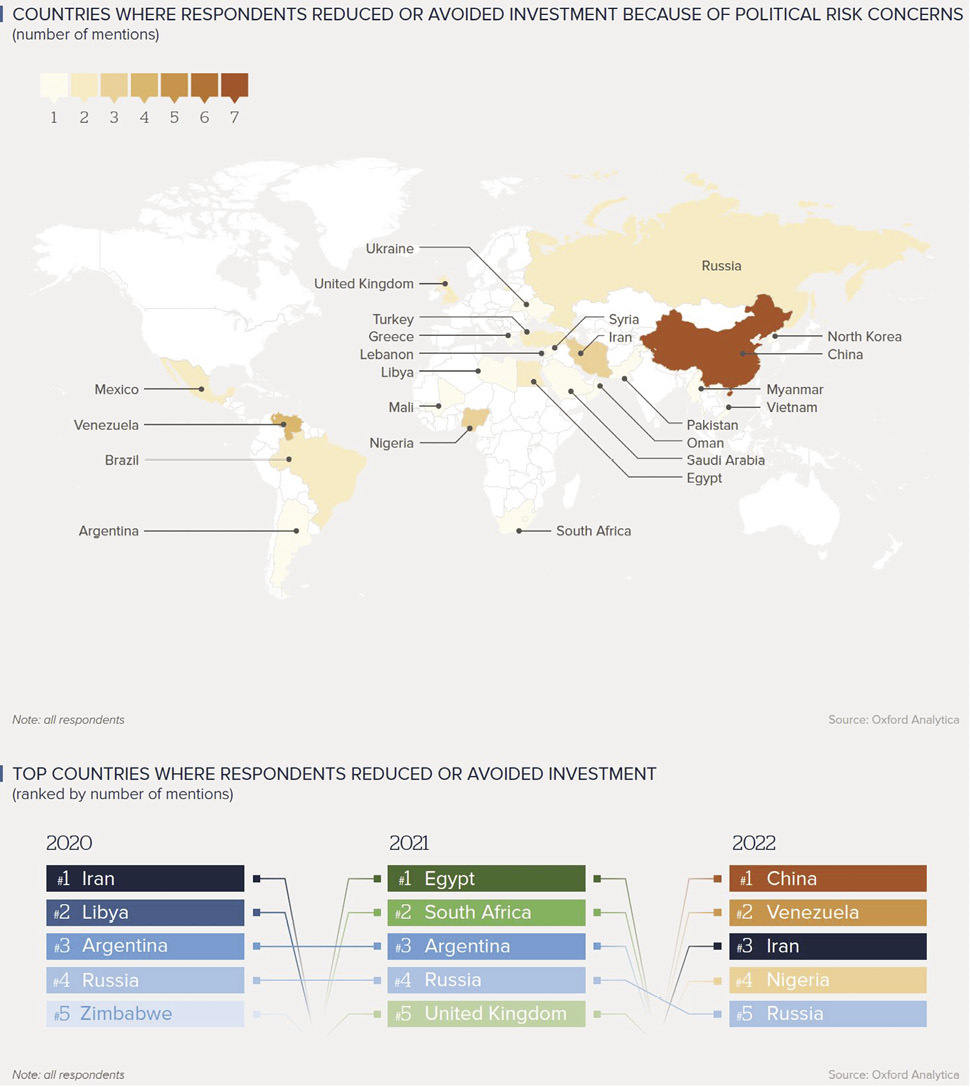

Like Apple, many Western manufacturers are gradually moving production to Vietnam. A good indicator of multinationals’ thinking is to be found in the insurance broker Willis Towers Watson’s 2022 political-risk report, published earlier this year.

The country in which the most companies now avoid making investments, the report’s survey found, was China, followed by Venezuela, Iran, Nigeria and Russia. (The survey was conducted before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.) The top spot for China was a remarkable change from two years earlier, when the top five had Iran in the top spot, followed by Libya, Argentina, Russia and Zimbabwe. This change of attitude appears to have been triggered by Beijing’s growing willingness to punish companies as proxies for their home government. It has, sotto

voce, meted out such punishment on Ericsson, Australian winemakers and the entirety of Lithuanian industry. The only companies that are somewhat protected from this caprice are lower-tech companies, which started moving manufacturing out of China years ago as a result of rising Chinese wages and Beijing’s desire for the country to move up the tech totem pole. But not even fashion is safe from geopolitics: last year Chinese consumer boycotts hit H&M, Nike and Burberry after the EU, the UK and the US imposed sanctions on Chinese officials.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, of course, triggered a massive exodus of Western companies from that country. Sanctions forced some of them to leave, while others did so because it was, as they said, the right thing to do.

Source: 2022 WTW Political Risk Survey Report

That decision may not always have been an altruistic one; rather, it was often triggered by the fear of a consumer backlash on the internet, so-called hacktivism. Unlike consumer boycotts of the past, social media-led boycott campaigns – so-called hashtag activism — don’t necessarily result in lost sales for the targeted companies. Instead, their effect is mostly reputational, and as a result it’s instantaneous. After the Japanese apparel chain Uniqlo announced on in early March this year that it would remain in Russia because ‘clothing is a necessity of life. The people of Russia have the same right to live as we do’, the brand was subjected to a massive protest campaign on Twitter, with users posting images of blood-soaked clothes. A couple of days later, the brand announced that it was leaving Russia. It joined the around 1,000 international companies that have announced they are curtailing operations in Russia or leaving the country altogether. The ones leaving the country, such as McDonald’s and Germany’s DIY giant Obi Baumarkt, have done so at a considerable financial loss.

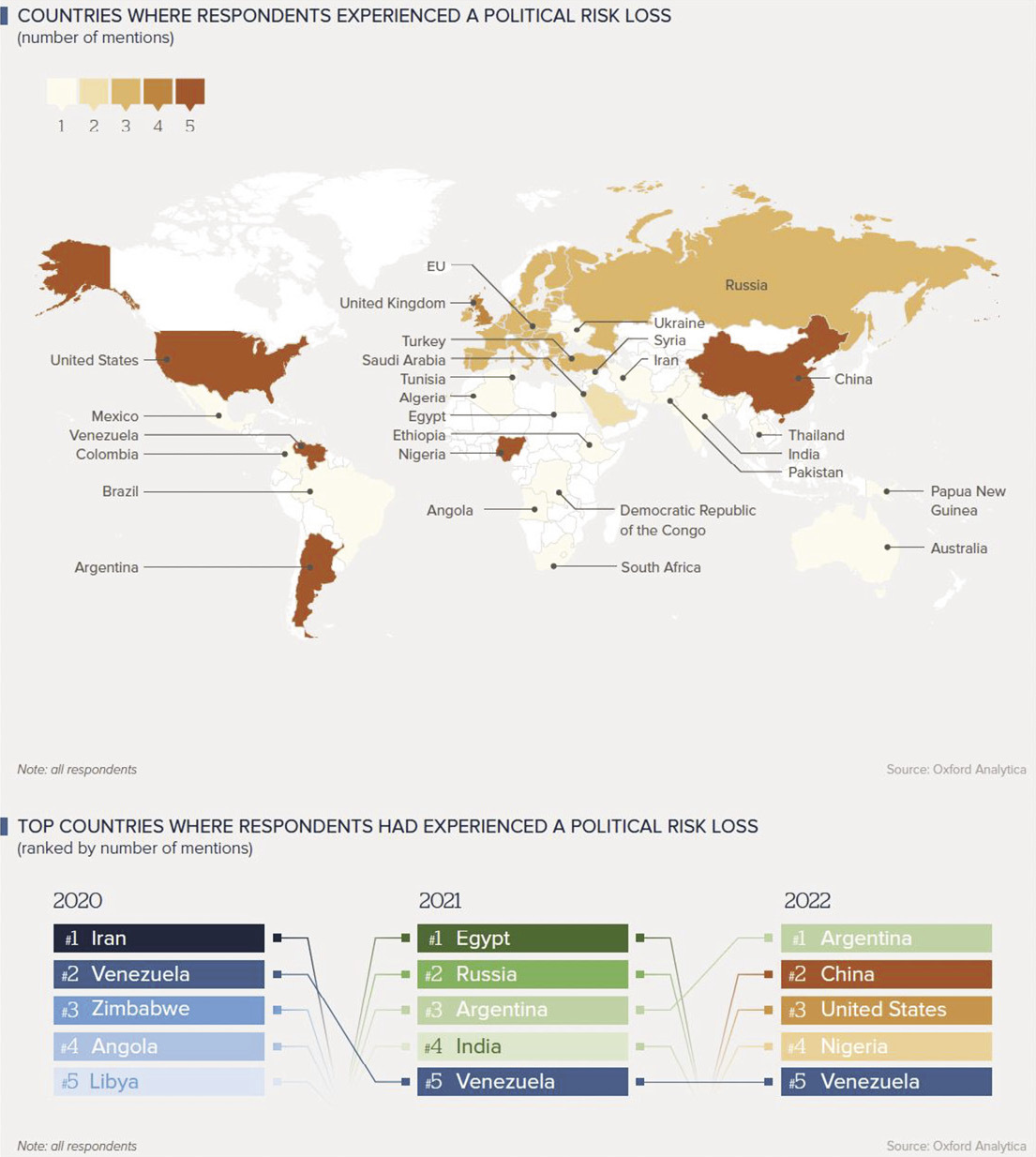

Source: 2022 WTW Political Risk Survey Report

But a generation of full-throated globalisation means that today’s companies depend on their globe-spanning supply chains and global sales. Suspending operations in Russia was relatively easy because for many companies it’s only a modest market, and most companies – except those minerals and other natural resources abundant in Russia – don’t rely on the country in their supply chains either. But China continues to play an enormous role manufacturing, supply chains and sales for companies of many sizes. To various extents, so do other countries that would not pass hashtag activists’ test for political purity: Saudi Arabia, the Gulf states, sub-Saharan African countries, Indonesia, North African countries, even Turkey. Yet to be able to keep manufacturing goods on which consumers all over the world now depend, and in order to keep revenues from collapsing, companies have to keep manufacturing and selling in such countries. During the Cold War, operations in countries outside the Western sphere were so limited that a forced withdrawal would have had little impact.

Today’s clash between globalisation and geopolitics, with consumer sentiment as a dark-horse factor, is setting them up for an uncomfortable existence. They’ll have no choice but to tackle these extremely serious complications, since otherwise their revenues will plummet – and Western national economies will hurt too. But the more than three decades during which global expansion was virtually every company’s goal and where companies could operate as a free-floating layer above sometimes squabbling nation-states is over.

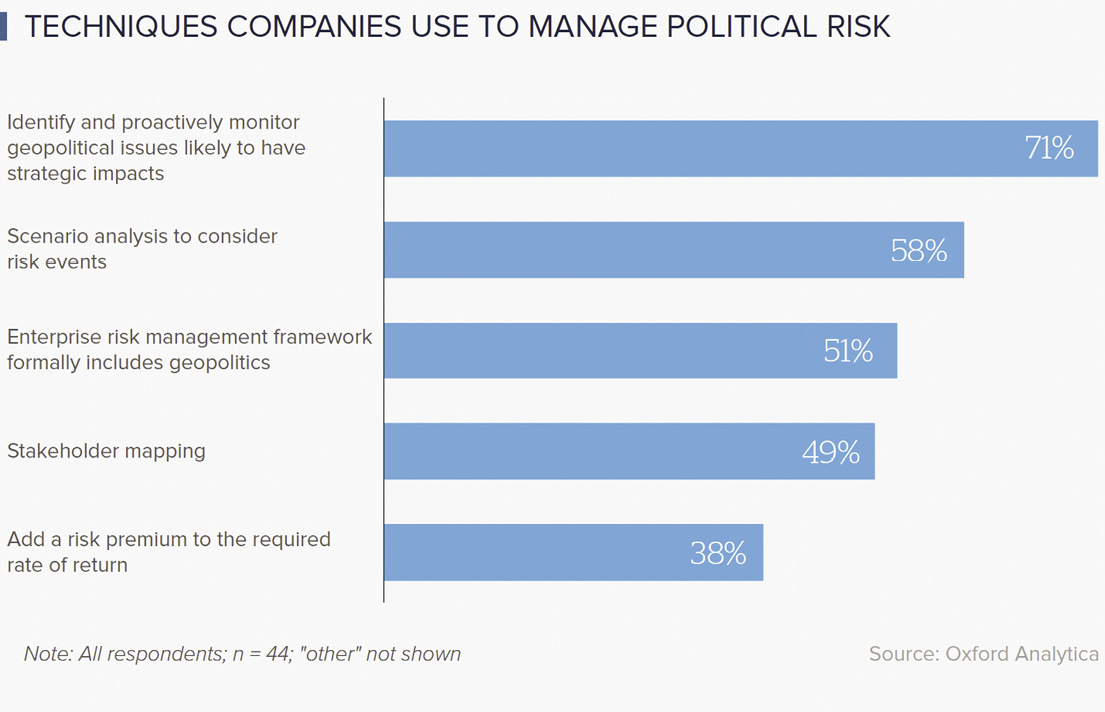

Source: 2022 WTW Political Risk Survey Report

As Russia’s war against Ukraine has demonstrated, companies can no longer exempt themselves from geopolitics on the grounds that commerce is neutral: governments can simply make them de-facto participants in geopolitical confrontation. Consumers, in turn, can demand that they take a position on geopolitical issues, too – and those consumers already include Chinese ones who (often in conjunction with the government) punish Western brands over alleged offences such as failing to include Taiwan on a map of China. The easy times of constant global growth aided by corporate neutrality are over. That’s indisputably regrettable. But the companies that manage to navigate these choppy waters will survive. They may even thrive.

Elisabeth Braw is a Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council, Senior Associate Fellow at the European Leadership Network, and a member of GALLOS Technologies’ advisory board. She is the author of The Defender’s Dilemma: Identifying and Deterring Gray-zone Aggression (2022) and Goodbye, Globalization (Yale University Press, 2024).