Winter 2022

Turkey’s Quest for Autonomy

In 2023 Turkey will celebrate the centennial of its Republic. By the middle of the year the voters will go to the polls to elect a President and members of Parliament. The results of the election will likely determine the trajectory of the Republic as it enters its second century. The voters’ choice will indicate whether the Republic will remain faithful to its founders’ project aspired by Enlightenment principles and a Western orientation or be reimagined by a religious-authoritarian alternative that was shaped by opposition to the original design.

In some sense these elections, as well as the direction of Turkish foreign policy as the Ukraine war unfolds, will also help crystallize the country’s relations with the West and the valued components of the Westernising project. The domestic battle for Turkey’s identity, what some authors call its Kulturkampf, between a religious authoritarian and a secular-democratic vision is part and parcel of the battle to shape the country’s foreign policy orientation and the principles that will guide this.

The Turkish debate over Westernization has never been a winner-take-all contest between supposedly pure Westernizers and retrograde Muslims. The strategic aim of Kemal Atatürk and other founding fathers of the Turkish Republic in 1923 was to be part of the European system of states, just as the Ottomans had been. Yet even among committed Westernizers there were lines that could not be transgressed, and suspicions that could not be erased when it came to dealing with the West. After all, the Republic had been founded following a bitter struggle amid the rubble of the empire against occupying Western armies. Its founding myths had an undertone of anti-imperialist cum anti-Western passion. This tension puts its mark on the domestic politics of the country and informs its seemingly confusing moves in foreign policy.

In his remarkable book of autobiographical essays on his hometown, Istanbul:

Memories and the City (2005), Turkey’s Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk observes that “when the empire fell, the new Republic, while certain of its purpose, was unsure of its identity; the only way forward, its founders thought, was to foster a new concept of Turkishness, and this meant a certain cordon sanitaire

to shut it off from the rest of the world. It was the end of the grand polyglot multicultural Istanbul of the imperial age … The cosmopolitan Istanbul I knew as a child had disappeared by the time I reached adulthood.”

In all his work, Pamuk reflects on the Turkish ordeal of Westernization and the “torn” soul of the Turks whose aspirations remain Western but are full of suspicion about their historical rivals. In Istanbul, Pamuk notes that “with the drive to Westernize and the concurrent rise of Turkish nationalism, the love-hate relationship with the Western gaze became all the more convoluted.” The Republic sought to Westernize, be part of the European universe, but kept its guard up against Western encroachments and did not quite trust its partners-to-be.

Today, the nationalist reflexes of Atatürk’s heirs – the secularist republican elites in society and still in some positions of power arguably play as large a role in the blossoming anti-Western sentiment as the Islamist political parties and the more religious segment of the population. Interestingly though, the youth who were born and/or grew under AKP rule are secular nationalists and pro-European by and large.

The religiously driven ideological bent of Turkish Foreign Policy in recent years bears the unmistaken stamp of the ruling party and its leader whose pedigree is in Turkey’s solidly anti-Western and anti-Westernizing Islamist movement. But there is also an element of continuity in Turkey’s foreign policy preferences since the end of the Cold War.

The thread of this continuity is the “quest for autonomy” and the desire to feature in world politics as a regional power. It is this underlying current that helps explain much of what Turkey does in its foreign policy that appears contradictory to outside observers and worries them and leads to the deepening estrangement between Ankara and its treaty allies in the Transatlantic Community. Militarily Ankara is a nearly impeccable ally and participant in NATO’s military exercises and operations, despite the penchant of its President for frequently expressing his desire to join the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, which was founded to contain and counter NATO’s reach. But Turkey can also be a gadfly in political matters as its recent obstruction of the strategically critical admission of Sweden and Finland into the organization underscores.

Turkey’s so far skillful ‘balancing act’ since the beginning of the war in Ukraine is one of those confusing moments for its allies. Ankara critically blocked Moscow’s use of its navy fleet in the Black Sea by calling the invasion and the ensuing military engagement a “war” and invoked the Montreux Convention which enables it not to allow the passage of belligerent parties’ battleships through the Turkish straits. It does not recognize the annexation of Crimea, supports Ukraine’s territorial integrity, sustains Kyiv’s war effort by supplying it with drones and other military matériel.

At the same time though, it keeps its line of communication with Vladimir Putin open, does not close its air space, does not join the sanctions régime, welcomes Russian refugees, oligarchs (and their yachts and money), helps broker agreements such as the grain corridor with the UN that alleviates a global problem of grain shortage and food price hike yet gets sternly warned by the US Treasury for its attempts to bust financial sanctions. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan can meet with both Vladimir Putin and Volodymyr Zelenskyy almost at will and has a “special” relationship with the former whose assent, support, or assistance he needs for several domestic and foreign policy matters.

‘Strategic Westernness’

During the recent G‑20 summit in Indonesia President Biden called an on-the-spot emergency meeting of the G‑7 and NATO members’ heads of government in Bali. NATO member President Erdoğan, although present at the summit, was not called to join and when asked about this, he curtly responded that he was only invited to “important” meetings and not to “unimportant” ones. His exclusion spoke volumes about Turkey’s relations with its treaty allies and exposed the deep estrangement between Ankara and other Western capitals and the mistrust that holds sway in relations. At a time when geopolitics is on the ascendant and Ankara’s strategic choices and diplomatic moves in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine are consequential for Western geopolitical goals, this perceived ambiguity in Turkey’s strategic identity is indeed a troubling factor for the Atlantic Alliance. Yet it is also an important factor of continuity in Turkish foreign policy in the post-Cold War era.

Different schools of thought in Turkey since the end of the Cold War pushed for a more expansive view of her strategic interests. With the dissolution of the Soviet Union in particular the urge to become an influential regional power in the former Soviet space sprang up. This first attempt at a “Eurasianist” foreign policy did create a presence for Turkey and its businesspeople but strategically the results remained modest at best. At the turn of the century the ascending view of Turkey’s national interest, despite a deep sovereigntist streak in strategic thought, was membership in the EU. That the European Union dropped the ball on Turkey first by admitting Cyprus as a member and then following the will of the German Chancellor and the French President not to make Turkey a member significantly contributed to the estrangement of Ankara.

Later, the financial and economic crisis of the EU diminished its lure economically. The Arab revolts of 2010-11 presented an ideologically defined geopolitical opening for the AKP government. Turkey assumed a more assertive regional power posture. At the beginning Ankara pursued this through the deployment of its soft power. Then, as the Syrian condition deteriorated and began to present a major national security problem there was a swift turn to hard power. The dramatic decision by President Obama not to punish the Syrian régime in August of 2013 after it used chemical weapons confirmed in the minds of the Turkish security elites that they could not count on Washington. In fact, the latter further alienated Ankara as it forged an alliance with the Kurdish PYD/YPG, the Syrian branch of Turkey’s nemesis PKK in the fight against the Islamic State.

But arguably, the most critical turning point for President Erdogan, by then in full command of Turkey’s politics, in calibrating his relations within the Transatlantic Alliance was the response of the allies on the night of the botched coup attempt of July 15, 2016. Whatever the full story of that traumatic event was, the allies’ reaction was inadequate, wanting in democratic solidarity and embittered both the public and the government that then used the occasion to undermine democratic rules and institutions in the country.

This was the moment that led Turkey to align itself with its historical adversary Russia with which it finds itself on opposite sides in many conflict areas and punctuated the beginning of their interesting pas de deux. As Professor Evren Balta of Özyeğin University observed: “Arguably the most important problem in Turkey-Russia relations is the fact that the cooperation between the two countries has never been predicated upon common principles, institutions or even a short-term common vision. These two countries that do not trust one another and have different understandings of their interests and of the threats they face, can only manage to have a partnership if a third actor appears on stage that both mistrusts more than one another.”

The purchase of the S‑400 defensive air missile system from Russia was arguably a decision that was consistent with this quest for “autonomy”. However, their procurement eventually led to Turkey’s expulsion from the F‑35 production network and cancellation of delivery of the aircraft Turkey ordered that were to be the mainstay of its strategic doctrine and air defense in the coming era. The backlash to the decision to purchase the S‑400s left Turkey vulnerable and isolated within NATO. Moreover, the move brought upon Turkey the wrath of the US Congress that forced the hand of President Trump who enjoyed a very personalistic relation with President Erdoğan to implement the CAATSA (Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act) legislation against Turkey. Currently, Turkey awaits the approval of the US Congress to buy F‑16 fighter jets and modernization kits for its existing fleet.

Despite the oddities and recriminations Ankara’s moves engendered though, Turkey managed to safeguard its core interests in her immediate vicinity. It used its relations with Russia to balance Western powers in its own “near abroad” meaning particularly Syria. At the same time Ankara did not shy away from using its NATO membership to balance the expanding power of Russia, particularly in the Black Sea. In other words, Turkey has followed a fine line between its allies and its northern neighbor, and that fine line was labeled “strategic autonomy.”

Source: newlinesinstitute.org

A lost battle in the Middle East

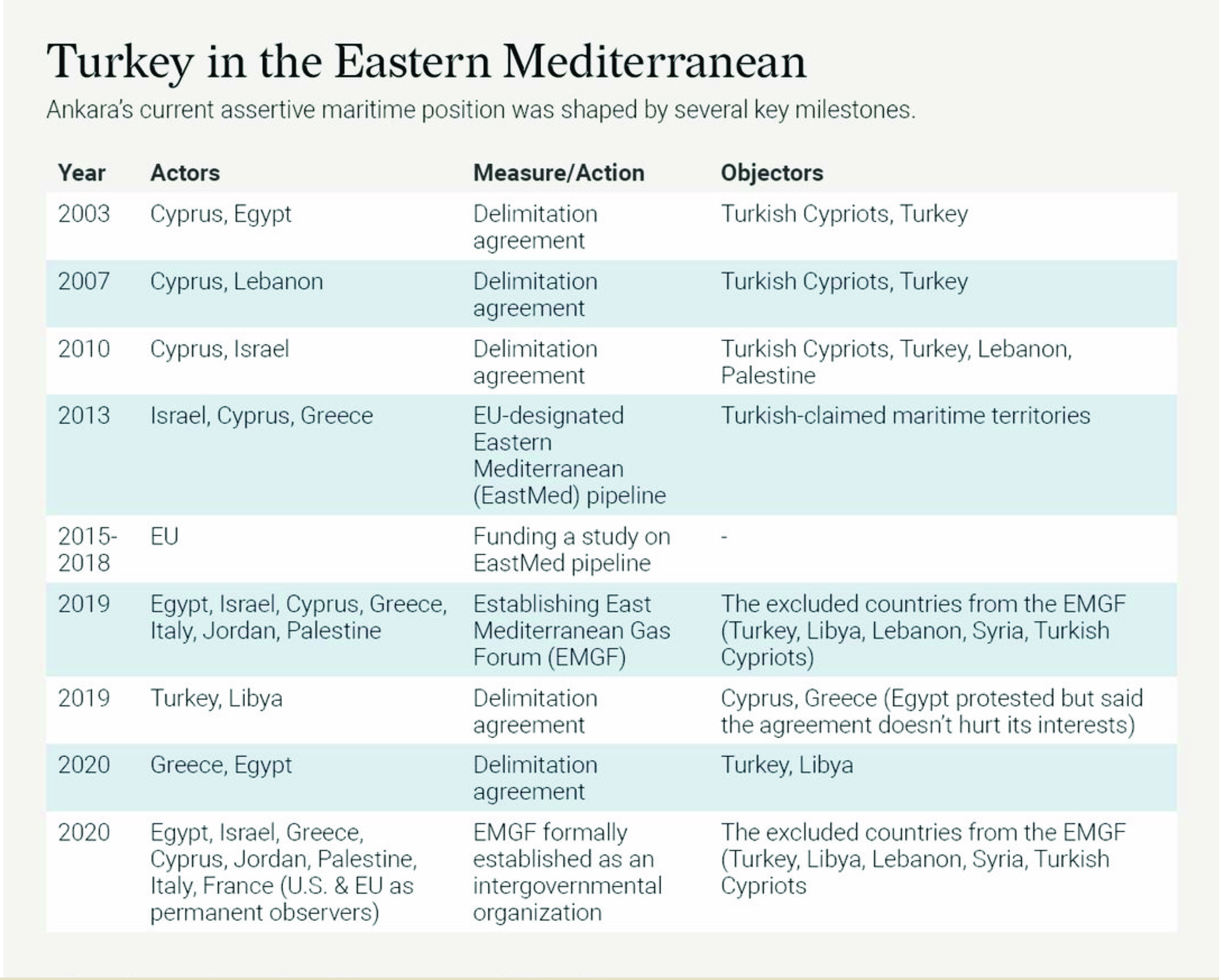

For a while, the more Islamically oriented strategic vision of AKP and the more nationalistic and decidedly anti-Western strategic visions of different security circles in the country have merged in supporting a set of policies that favored power projection, military bases, exaggerated maritime rights in the Mediterranean basin, and a wide autonomous space in pursuit of Turkey’s interests. A doctrine developed by secular nationalist officers, “The Blue Homeland” tailed and justified Erdoğans’ policies in the Eastern Mediterranean and Libya. This opening was also an attempt to break the quasi encirclement of Turkey by a set of Eastern Mediterranean countries. These joined forces to counter Turkey’s assertiveness and hardline policies and in so doing trampled upon its legitimate rights and concerns. The rising importance of the Eastern Mediterranean’s energy reserves and the competition to explore those added a new dimension to the already tense relations between Turkey and the Republic of Cyprus and through it with Greece that took advantage of Turkey’s isolation in the region to forge close knit relations with Egypt, the Gulf countries and Israel as well as France and the United States.

For Erdogan there was another dimension to his policy towards the Middle East. It relates to the geopolitical cum ideological rivalry with the UAE and Saudi Arabia and their ally Egypt, for leadership of the Sunni Muslim world with Qatar as its ally. To that end the campaign to build mosques throughout the world, using the Directorate of Religious Affairs as a parallel foreign service in Western countries that have Muslim populations, and championing the cause of Muslims everywhere continues unabated. Unless, of course, that campaign should disrupt economic or geopolitical interests as is the case in the deafening silence over the abysmal treatment of the Uighur Turks in China. Heavily invested in the success of the Muslim Brotherhood throughout the region even long after its defeat was sealed and political wings clipped, Turkey gave shelter to thousands of members of the Brotherhood in exile, allowing them to broadcast to Egypt from Turkey. At the end though Turkey failed in its attempt to be a hegemonic power in the Middle East. After years of harshly condemning them, efforts were made to rebuild bridges with UAE, Saudi Arabia, Israel, Egypt and even Syria. The “precious loneliness” of Turkey, a term coined by Presidential advisor İbrahim Kalın, turned out to be not so precious after all. The country’s economic vulnerabilities, its chronic problem of governance and its self-inflicted solitude in the region made it imperative to mend fences. The reconciliation may work but Turkey will be in a much weaker position than where it was when the bid for hegemony was launched.

In almost all these issues the Turkish move was a response to a strategic void or vacuum or challenge. The retrenchment of American power and its neglect of Turkish concerns led to the interventions in Syria. In Eastern Mediterranean, although Turkey’s isolation was its own doing, Turkey reacted to the moves of an adversarial bloc of countries by defiant military moves, heightened rhetoric but at the same time with an invitation to put all the interrelated matters (Eastern Mediterranean energy; Aegean issues with Greece; Cyprus; Libya) on the table for a grand diplomatic bargain to solve them all together. Ankara signed a military cooperation agreement with the internationally recognized government in Tripoli that was being attacked by rebel forces supported by UAE, Egypt, irregular Russian forces, and France and intervened militarily when no other country would come to that government’s help.

In the Caucasus it helped Azerbaijan break the gridlock in the “frozen conflict” of Karabagh exposing the lethargy if not outright complacency of the Minsk group whose members included the USA and France alongside Russia. On the tug of war with Greece during the dangerously tense summer of 2020, Ankara believed that the EU could not be an honest broker, that it could not control Greece’s behavior. In turn, the EU saw Turkey as the aggressor and in the case of Germany as a country that broke its promise when Turkey sent its exploratory ship Oruç Reis back to the Mediterranean with a new Navtex after Berlin brokered an agreement and NATO was intervening in the dispute. Ultimately though, belligerent rhetoric notwithstanding, Turkey refrained from a repeat of the summer of 2020 and let waters calm. Even the recent escalation of a war of words with Greece is more likely to be for domestic consumption than the sign of genuine martial intent.

Which direction hence?

The Russian invasion of Ukraine changed the strategic landscape in the world considerably and laid out the contours of an emerging world order that can be defined as asymmetric multipolarity. The European security structure that was predicated on taming Russia by commercially integrating it to European markets collapsed. A major war launched by a powerful authoritarian country against a smaller and weaker neighbor resurrected long forgotten or suppressed memories of Europeans and led them to respond strongly against Russia with a series of sanctions packages. The gradual withdrawal of the USA, whose military-technological might and indispensability for European security were reinforced, from Europe was arrested; NATO emerged as the central organization of a soon-to-be rectified Atlantic Alliance and the larger systemic West that includes countries in Asia and Oceania. Russia will emerge considerably weakened and possibly destabilized out of this ordeal and will have to content itself to play second fiddle to a gradually more abrasive China. Caught off-guard by Putin’s failure China had to thread carefully so as not to fall on the wrong side of Western sanctions régime. It also felt helpless when Speaker of the US House of Representatives visited Taiwan.

A more striking feature of the post-Ukraine world order is that the West does not command as much authority as it used to. The so-called global south, convinced that we have entered a post-Occidental stage in world history, did not support the sanctions imposed on Russia. Many countries saw this not as a global affair but one that was limited to the European theatre. Collectively the global south will be more assertive, and some regional powers will have the ability to resist Western demands and follow their own proper agenda as most remarkably Saudi Arabia did during this crisis. Riyadh made President Biden come for a visit and even failed to stick to an agreement not to lower oil production.

Turkey is one of those regional powers that because of its geopolitical importance, the size of its economy and its institutional affiliations enable her to be a consequential actor in world politics and a force to be reckoned with. She will also benefit from the weakening of Russia, as the Black Sea will become less of a geopolitical pressure area for Ankara. The caveat is that these advantages need to be well managed, her diplomacy must be consistent, constructive, and the bellicose language must be dropped. Most importantly, the rulers of Turkey, present and future, must recognize that membership in alliances does not preclude strategic autonomy. In turn, Turkey’s allies particularly the Europeans will have to fully appreciate her overall importance and make an effort to build a new, more egalitarian and imaginative relation not just with Ankara but with Turkish society as well.

Source: newlinesinstitute.org

The author is a senior lecturer at Kadir Has University in Istanbul and a columnist at Habertürk daily newspaper. Currently, he is a Tom and Andi Bernstein Fellow at the Schell Center, Yale Law School.