Winter 2011

China: Middle Kingdom, but Not the World's New Centre

The scale and speed of China’s material rise over the last three decade make it inevitable that an increasingly uncertain world looks to the People’s Republic for salvation in testing times. Given what has happened since the mainland replaced Maoism with market-led economics at the end of the 1970s, it may seem a foregone conclusion that this will be China’s century as the once-great power in the East regains the strength it lost during a century-and-a-half of internal discord, weak government, invasion and humiliation at the hands of foreigners followed by three decades of Mao Zedong’s murderous adventurism.

That conclusion is, however, wrong, for a variety of reasons, some external but most internal. Which say much about the nature of the last major state ruled by a Communist Party. While the emergence of the People’s Republic on to the world stage has been the most significant global event since the end of the Cold War, the very scale and pace of growth has been such that the ‘China Model’ is in need of serious modification, let alone being capable of taking on the role of a foundation stone for the world.

The leaders in Beijing — both those in power today and those who will take over from the autumn of 2012 — know this. The Prime Minister, Wen Jiabao, has spoken of the country’s pride and joy, its economy, as being unbalanced, uncoordinated and unsustainable. Rebalancing is the watchword of the current Five Year Plan, which runs to 2015. China needs to boost consumption, which has been held back while capital has benefitted most from economic expansion. It needs to move up the value chain, to get away from the 1980s model of low-cost labour exporting deflation to the rich nations of the world. It needs to improve energy efficiency, fight pollution more effectively and liberalise capital markets.

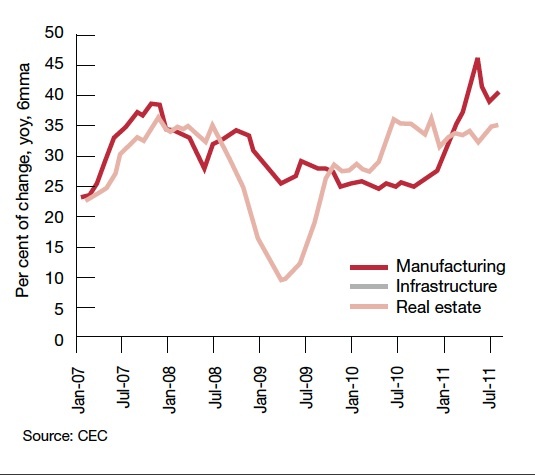

There has been some movement. Government policy shifted in the summer of 2010 to favour pay rises for blue-collar workers, including the aim of doubling the minimum wage by 2015. Investment is moving from infrastructure and property to machinery to raise productivity and get China into more sophisticated industries than the basic manufacturing of the first generation of growth. (see chart below). Western China is being developed to balance the build-up on the coast of the last three decades, with the explosive growth in the mega-municipality of Chongqing, the modernisation of the Yangtze River as a freight channel and the technological focus on the Sichuan capital of Chengdu.

Growth in investment

Source: CEC

The leaders in their Zongnanhai compound are keen to promote such changes, even if implementation on the ground does not always match the intentions of the centre. But other reforms which are required if China is truly to progress are more tricky.

China needs deep structural reforms if it is to raise its game to meet an increasingly challenging environment. But these have been repeatedly put off in recent years because they raise knotty issues, which the consensus leadership has preferred to sidestep.

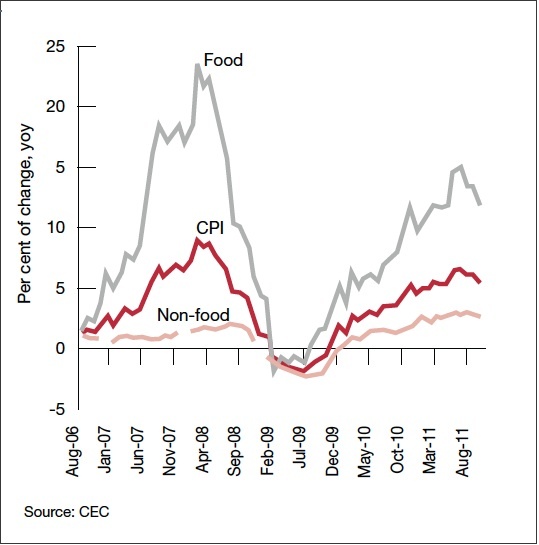

For instance, state ownership of farmland, which is parceled out to leaseholders in small plots, leads to an inefficient agricultural sector compounded by loss of arable land through urbanization and desertification, a serious water shortage in the wheat land of the north of the country and poor distribution systems. Though harvests have been good in recent years, the outcome is constant underlying price pressure on food at a time when the old 2 per cent annual CPI inflation, which China enjoyed for much of the first decade of this century, has gone forever.

Food drives inflation

Source: CEC

Equally, the hukou registration system that ties migrant workers to their home villages for health, education and welfare — even if they work far away in coastal regions — impedes labour mobility and creates an underclass of urban workers who do not have the right to purchase accommodation in the cities where they work. Local governments need to be given enhanced revenue-raising powers to meet their obligations for spending on health, education, welfare, pensions and social housing and diminish their reliance on reclaiming agricultural land from farmers, reclassifying it for residential, industrial or commercial use and auctioning it off to developers.

The legal system is too often in the thrall of politics and power-holders. The backward financial system, controlled interest rates and the use of credit quotas produce big misallocations of capital. Low state-imposed prices for energy and water lead to wastage. The growing power of the state sector has diminished the role of the private entrepreneurs and SMEs that played such a key role in the growth spurt after Deng Xiaoping put his weight behind market-led reform in the 1980s. Political connections play an ever-increasing role and corruption remains a major sore. The need for a major reform programme is, therefore, evident but runs into a series of obstacles. China’s success in restoring growth to above 9 per cent after the downturn at the end of 2008 and beginning of 2009 inevitably saps the impetus for change in the face of entrenched interest groups at national and regional level. As the Communist Party shapes up for a major change of personnel at the very top at its next Congress in the autumn of 2012, nobody wants to be seen to be rocking the boat. Beyond that, some of the needed changes involve major political and financial issues.

For instance, privatising ownership of farmland to encourage the development of larger-scale agriculture would mean that local governments would have to be given greater means of raising cash from other sources. But increasing provincial tax powers would increase their autonomy at a time when the central authorities are trying to rein in spending at local level after the credit splurge of 2009. Beijing would lose at least some of the grip it exercises through its remittances to provinces from centrally collected tax revenue. Relaxing the hukou system would mean that cities would have to be given more cash to fund welfare services and the security services would lose a means of social control – a major concern at a time when China experiences more than 100,000 protests a year.

Strengthening the legal system would inevitably raise the question of whether the Communist Party, which runs its own disciplinary commission, would come under the law. Rather than moving in that direction, the Chief Justice has told judges that their prime duty is to strengthen the Party, a line consistent with the insistence of the leadership that the Party alone can deliver growth and ensure stability and national unity; all of which would be jeopardised by competitive democracy as practiced not only in the West and, closer to home, in India but also across the 100-mile Strait in Taiwan.

As if such challenges were not enough in themselves, China faces them at a time of external economic uncertainty as its main export markets grow stagnant, or threaten to head into outright recession. The economic revolution that began in the 1980s rested not only on abundant cheap labour and capital but also on global demand, which lapped up goods from the mainland. That enabled the People’s Republic to grow while its domestic demand remained low (and, indeed, to privilege capital over labour in sharing out the fruits of growth).

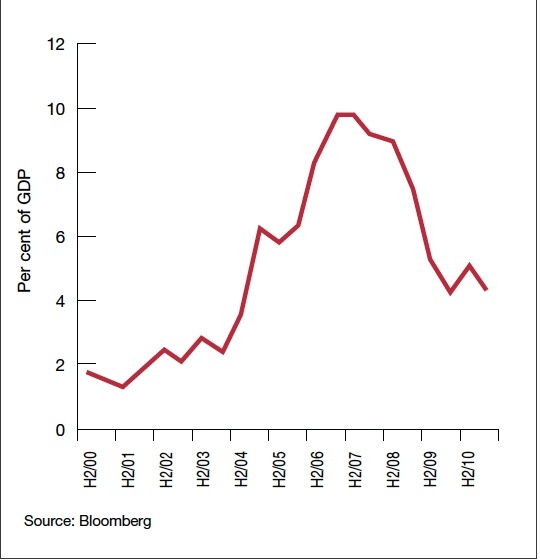

The share of trade in GDP growth has halved since the boom years of the middle of the last decade. But it still remains a key factor for the vast network of SMEs, particularly in the east coast provinces, which are under pressure from the government’s belated policy of boosting wages together with tighter credit and slower payment from foreign buyers.

Trade as a contribution to GDP

Source: Bloomberg

So, while some in the West ask if China can save the world (or, at least, respond to President Sarkozy’s appeal to support the euro) China’s concern is rather how much damage it will suffer from the developed world. Beijing’s line has been quite clear. The West must get its own house in order rather than seeking succor from a nation which, however big its foreign exchange reserves, still houses hundreds of millions of people living in relative poverty and is still in the development stage towards achieving what its rulers set as the goal of realising a ‘moderate prosperous society’.

At the end of November, the Commerce Minister, Chen Deming, was quite blunt in telling a conference that Europe had yet to take any significant step in tackling its debt crisis. If it wanted help from China, he made clear, it would have to ‘be more open to us in return.’ In other words, China would expect to be granted full market status by the EU and to be allowed to buy the technology firms it wants to acquire without restrictions on national security grounds. Going a step further, Chen added that his country had ‘over-pledged’ when it joined the World Trade Organisation (WTO) ten years ago.

Having adopted a low global profile politically in keeping with Deng Xiaoping’s admonition to keep its head down while it grew, China is now in a more assertive mood, as nationalism grows and it contrasts its recovery since late 2008 with the woes of the West. It knows full well the pivotal position it occupies in global commodity demand and its key part in the shift in the centre of the world’s gravity to Asia. It is a major contributor to funding the US federal deficit and a major supplier of aid to Africa. It seeks, with varied degrees of success, to conduct soft power diplomacy, notably through its Confucius Institutes. It holds a permanent Security Council seat, is a nuclear power and is fast developing its armed forces, especially its navy. It therefore feels ready to re-assume the role of the Middle Kingdom as it reverses the decline from the glory era of the High Qing around 1800 through the travails of the 19th century and the first three quarters of the 20th century.

But it is, at the same time, a somewhat hesitant great power. It lacks a coherent global policy. It defends its ‘core interests — the political system, its right to rule Tibet, recovery of Taiwan – and pursue resources diplomacy from Australia to Angola via Brazil and the Middle East. But it has recently misplayed its hand in its own region, antagonising other powers such as Vietnam and the Philippines by its assertive claims to sovereignty over the whole of the South China Sea. This created an opening through which President Obama gratefully walked at regional summits in November 2011, to solidify the US claim to be, as Hillary Clinton puts it, a ‘resident power’ in Asia. The budget of the People’s Liberation Army is rising by 12 per cent a year but its armed forces are still far behind those of the United States, whatever the sabre-rattling by some of its generals.

The ‘Chinese Model’ and the ‘Beijing Consensus’ conjured up by commentators carry little conviction outside the People’s Republic. China simply has too many major domestic issues to deal with to become a new centre for the world. It is, genuinely, a special case because of its size, its history, its diverse nature and its peculiar system of state capitalism.

As such it will remain of huge importance for the rest of the globe for decades to come. But it will not take on the role played by the United States since 1945 as its political system remains committed to the defence of one-party rule as its prime objective, treading an increasingly fine line between allowing greater individual liberties while squashing any threat — real or imagined – to Communist Party rule as in the recent brutal crackdown on human rights lawyers and the tide of repression which made a mockery of any hopes than the 2008 Beijing Olympics would bring relaxation. Tibet is under heavy security guard, especially after the self-immolation of a dozen monks this winter. Money is being poured into the huge western territory of Xinjiang, as it is into Tibet, but the local people complain that most of the benefits accrue to Han Chinese immigrants while the army and police keep tight watch on any sign of dissidence.

Life for the majority of Chinese citizens will go on improving but, at the top, the status quo will prevail offering little beyond material improvement to a population whose horizons are steadily widening in an era of social media and exposure to outside influences. For the moment, materialism rules, as epitomised by the young woman on a dating show who said that she would ‘rather cry in the back of a BMW than laugh on the back of a bicycle’. But whether this will be enough to sustain the régime is one of the major questions for the coming years, particularly if economic growth slows and the negative by-products of that growth – from corruption to environmental degradation – become increasingly irksome.

China suffers from a widening trust deficit in which people have little faith in the authorities – as the saying goes ‘only believe something when the government denies it’. There are recurrent safety scandals involving everything from food and medicines to the high-speed train crash last summer which brought into question an iconic symbol of the country’s ability do anything faster and bigger than anywhere else – and revealed a major corruption scandal as well. The much-praised new opera house in Guangzhou developed cracks and collapsed windows within a year of its opening. The property market, in which so many of the middle class have invested in the face of negative interest rates, rides on a knife edge. The Chinese as a whole may have grown better off, but the extent of enrichment by the really wealthy is a growing cause for resentment as a new class of ‘princelings’, children of first generation Communist leaders, makes the most of their inherited status.

The new leadership, which will take over in 2012–13 under the princeling Xi Jinping is aware of the challenges that face it, and the country. But the consensus style of leadership which has been apparent for the last halfdozen years appears likely to continue, This is healthy in the sense that China is no longer subject to the whims of a Mao. But the Chairman of the Board style of leadership operated by Hu Jintao during his ten years at the top Is illfitted to cope with the major structural reforms that will be needed in the coming decade. The boss of Chongqing, Bo Xilai, has made a name for himself with a campaign to encourage ‘red songs’ and patriotic nostalgia harking back to the Mao era, but this is hardly enough to motivate a nation in which opinion polls show a majority of people saying that they feel ‘vulnerable’ amid the high-velocity society and economy bred by thirty years of headlong expansion.

From a revolutionary nation, China is fast becoming a strange mixture of a febrile nation hooked on growth but also a status quo power, cautious about using its financial power or getting itself involved in the global responsibilities and entanglements which go with being a great power. As Wen Jiabao has put it, China can only depend on itself. So, in its way, China’s rise may only add to the vacuum at the global centre.

Jonathan Fenby is China Director of the research service, Trusted Sources and author of The Penguin History of Modern China. His book on contemporary China, Tiger Head, Snake Tails, will be published in April 2012.