Winter 2025

China’s Controlling Stake in Asian Security

The world’s fastest growing region, the Indo-Pacific, benefits from the fact that it is home to four different role models for how to think about critical national infrastructure, models that also show how defining what is truly critical depends on each country’s situation. Two of the role models are of countries that have for seven decades defined “critical” in terms of security against

a constant threat from their neighbour: Taiwan and South Korea. One has defined it in terms of vulnerability to natural disaster and of concern about resource, especially energy, supply, although security threats

are now taking greater prominence: Japan. And last but not least there is China, for whom critical national infrastructure has really become about the quest for strategic control.

Naturally, many concerns are shared between these role models as well as with the many other nations of this vast region: cyber security and the protection of national power grids both against failure and against hostile attack are prominent among the interests shared

by all. But where countries differ is in how much expense and especially redundancy they deem necessary for such infrastructure. Which means that they differ in their judgements about what is really meant by critical.

Take Taiwan as the extreme, benchmark case for the consideration of security threats. It has to think about what might happen if China were either to attempt a full invasion of the Taiwanese islands or if it were to mount a blockade of some sort against air and sea traffic

into and out of the main island, where the vast bulk of the population resides. But it also has to consider a different sort of security threat: the use by its adversary of information warfare and other forms of disruption in order to influence public opinion, manipulate democratic outcomes and destabilize society.

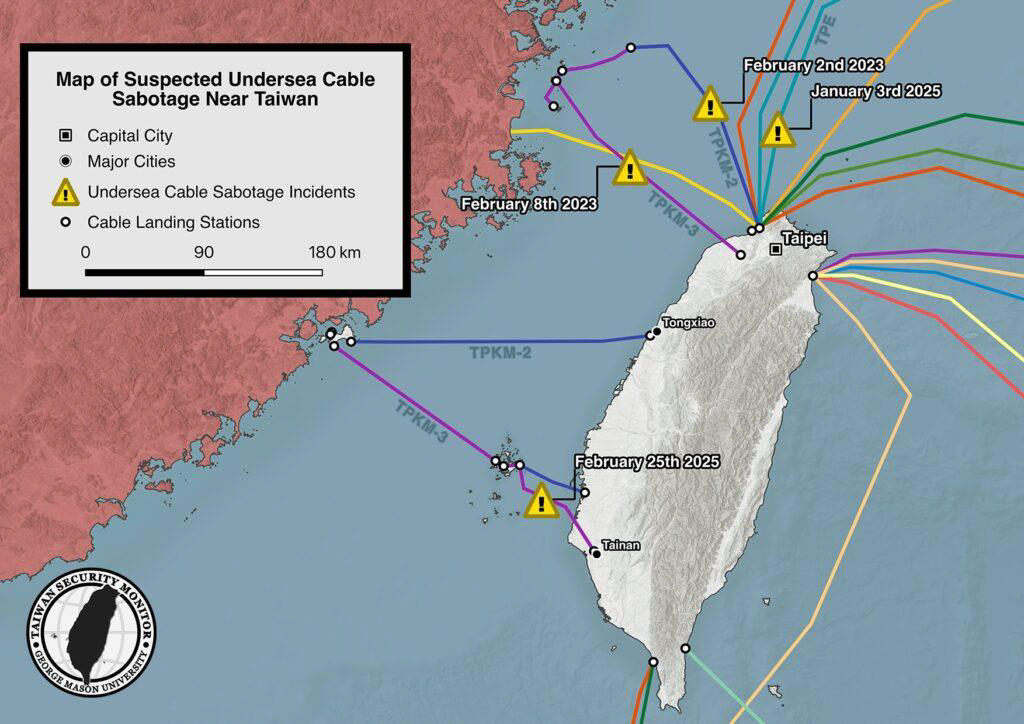

Every wargame for an invasion or blockade agrees that a critical issue for Taiwan would be whether it can maintain control over communications systems, both within the country and externally. Military and political planners’ greatest fear is of being blinded and silenced by Chinese electronic warfare and by the severing of undersea cables. In February 2023 two cables connecting Matsu, the nearest Taiwanese island to China, to Taiwan’s main island were severed by Chinese ships, leaving the island cut off from communications for two months. In wartime, such an event could be catastrophic.

For that reason, a central part of Taiwan’s defence strategy has become investment in redundancy in cables and satellites, especially geostationary satellites. One weakness in managing undersea cables is that Taiwan has no repair ships of its own, relying instead on international providers: while having its own ships would make little difference in the event of an invasion, controlling the repair process could be critical during a blockade.

The most important effort being made is to diversify Taiwan’s contracts with networks of geostationary satellites, essentially to avoid dependency on Elon Musk’s Starlink, and to build extra resilience through establishing multiple signal connection sites. Japanese communications satellites and networks are collaborating with this effort: in a crisis, communications promises to be one of the main contributions Japan will aim to provide to Taiwan, along with associated electronic warfare capabilities.

Beyond direct defence, communications and the constant task of countering disinformation, Taiwan’s situation, like South Korea’s, makes a further sort of infrastructure of vital national importance: inventories of energy, water and food supplies in order to lengthen the amount of time Taiwan could withstand an invasion or blockade and to give the Taiwanese public greater confidence that resistance and survival are both practical options. This is an aspect of critical infrastructure that Taiwan has neglected in the past, as storage is costly and conflict has not seemed imminent. But as that changes, so stockpiling is becoming a bigger priority, as is training and preparation for civil defence.

As for many countries, the goal of energy security clashes with other domestic political priorities: Taiwan’s ruling party, the Democratic Progressive Party, champions resilience and autonomy at the same time as being dedicated to phasing out all nuclear power generation. Investment in solar and wind power is rising, but this carries some risk of dependence on Chinese suppliers of equipment and battery storage. Stocks of liquefied natural gas currently cover only about 14 days usage; the national oil stocks cover 30 days. For a country contemplating a long potential siege, this is plainly inadequate.

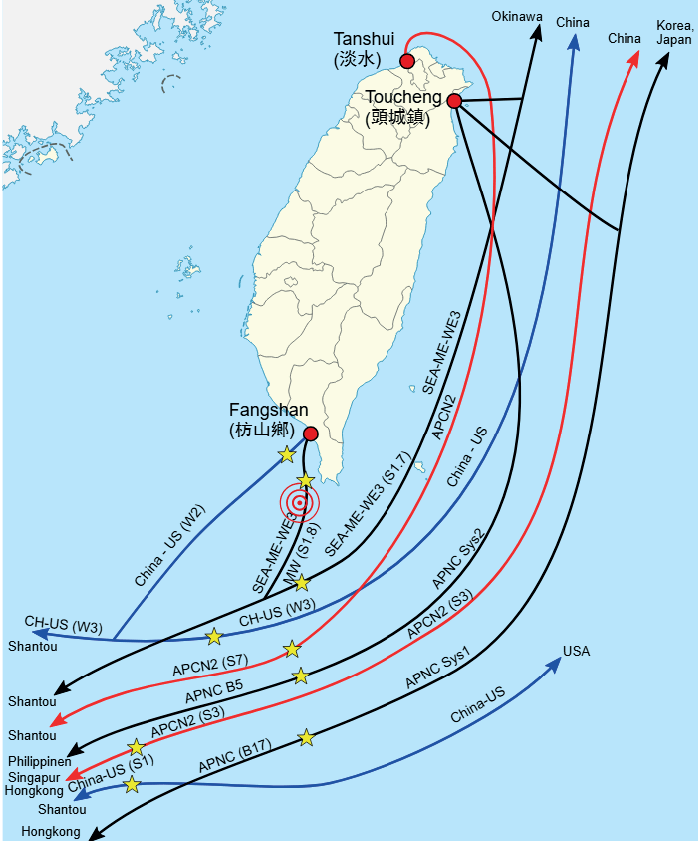

Japan does not expect to come under siege. Nor is it as vulnerable as Taiwan is to the severing of undersea cables as it has a greater number of connections, many deep under the Pacific. But it has nonetheless become a keen participant in initiatives by the Quad (India, the

United States, Australia and Japan) to encourage greater redundancy to be built into the cable system, notably including new cables planned and being laid across the Pacific to Australia via Christmas Island. It is also a keen investor in and developer of repair vessels, including Underwater Autonomous Vehicles (UAVs) and cable monitoring technology. Japan’s biggest infrastructure concerns, however, lie elsewhere: in energy security and cyber security.

The focus on energy has been a long-term one, given Japan’s lack of indigenous resources and long distances from fossil fuel suppliers. It was starkly highlighted by the 2011 earthquake and tsunami that led to the near meltdown of the Fukushima Dai-Ichi nuclear power plants and to the mothballing or shutting down of a Japanese nuclear energy fleet that had been supplying 30% of the country’s electricity and was destined to supply 40% by 2017. Of 33 operable reactors, 14 have restarted since the disaster and two new reactors are under construction.

Efforts to restart more plants have run into regulatory and political obstacles. The new prime minister, Sanae Takaichi, has pledged to accelerate this process and to facilitate the development of further new reactors, including small modular ones, but without a working majority in the Diet and with many local authorities opposed her chances cannot be described as high.

Source: Taiwan Security Monitor/George Mason University

Without nuclear power, Japan feels more vulnerable to geopolitical disruptions, which is why it has followed a hedging strategy on energy security: purchasing more liquefied natural gas from America while maintaining investments in the joint Russian LNG project at Sakhalin; encouraging solar power, especially on rooftops, and battery storage while also encouraging domestic development of alternative battery technologies that promise to reduce dependence on Chinese suppliers and critical minerals; facilitating what has become known as “urban mining”, the recycling of valuable metals such as titanium and indium using advanced smelter technology. Having been in 2010 the first country to be coerced by Chinese restrictions on exports of critical minerals, Japan has also been at the forefront both of transferring recycling technology to others in South-East Asia and of investing in mines and processing all across the Indo- Pacific.

For Japan, avoiding dependency on others has become an important theme in policies towards critical infrastructure and supplies. While it has no choice but to remain closely tied to the United States, Japan is seeking whenever possible to develop other options, such as the Global Combat Air Programme for advanced fighter development that it has launched with the UK and Italy rather than its traditional American suppliers, and its efforts to manage its own national cyber-defence force rather than collaborating with American suppliers such as Palantir.

This is proving to be challenging, for a critical shortage in Japan is that of software engineers. Until its revamping of its national security strategy in 2022 Japan had relied principally on private sector cyber capabilities; now the government is trying to recruit and train a national cyber- defence force that is growing from 500 to 20,000 hackers and engineers in the space of just a few years.

The reason why cyber security has risen to become considered as a critical part of defending national infrastructure is that Japan now feels itself to be on the frontline of actual and potential conflict with its three often aggressive neighbours – China, Russia and North Korea – and has decided that if it is to protect itself against such threats it must become a more active contributor to the US-Japan security alliance. But in doing so, both in the cyber and conventional military fields, its crucial modern vulnerability is its declining and ageing population and hence its shortage of labour.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Many of the smaller countries of South-East Asia look to Japan as both an exemplar for how to diversify supplies and maintain autonomy, even within the clear constraints of the US-Japan alliance, and as a source of aid, investment and technology for their own efforts to build autonomy and protect infrastructure against

threats. What they all share most clearly with Japan is the sense that the openness of the shipping lanes passing through the East China Sea, the South China Sea and the Western Pacific is part of their mutual infrastructure. The goal of maintaining a “Free and Open Indo-Pacific”, or FOIP, first deployed by Japan’s late Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, is more than just a slogan: along with the cables that run beneath it, it is a shared lifeline for all the countries of the region.

The big perceived threat to that lifeline is, paradoxically, the country that on some measures depends on it the most: China. Of the estimated one-third of global trade in goods that passes through the East and South China Seas, a very large share is going in and out of China. This gives the world’s second largest economy a powerful motivation to keep the sea lanes flowing, but also a strong desire to control them – or, put more minimally, to ensure that no one else, for which read the United States, is in a position to interfere.

This desire for strategic control and hence autonomy is the essence of China’s approach to its critical national infrastructure. Strict information control and surveillance, along with rapid development of artificial intelligence, are the principal domestic tools for this goal. But the seas adjacent to its shores are also part of that infrastructure, which is why China has built military bases on reclaimed land and reefs in order to be able to exert control, if it needs to. Other littoral nations and countries depending on those sea lanes fear that control becoming a form of leverage, as has been demonstrated by China’s export controls on its rare earth minerals.

Beyond that desire for strategic control, however, China’s other main drive has been to try to achieve greater self- sufficiency in as many sectors as possible: the so-called “dual circulation” strategy first promulgated in 2020. This has had an aim of reducing the economy’s reliance on international trade alongside measures to build greater redundancy and stability into energy supply through investments in renewables and in battery storage. By dint of the country’s vast size and high rate of investment, even at the cost today of over-capacity and intense domestic price competition, China has a better chance than most of achieving this goal, even if it cannot ever be entirely self-sufficient.

The good news for the Indo-Pacific is that there are so many role models demonstrating the different varieties of critical national infrastructure policies, and that most countries in the region are increasing sufficiently in prosperity to be able to finance improvements in such policies. The bad news, as for all countries, is that the potential dangers, especially technological but also geopolitical, are increasing all the time. It is a race to keep up that can never definitively be won.

Bill Emmott is Senior Adviser on Geopolitics at Montrose Associates. He was Editor-in-Chief of The Economist for thirteen years and former Chair of the Japan Society and the International Institute for Strategic Studies. He is author of Rivals: How the Power Struggle Between China, India, and Japan Will Shape Our Next Decade and his most recent book is Japan’s Far More Female Future, published in Japanese by Nikkei in July 2019 and in English by Oxford University Press in 2020, author of Deterrence, Diplomacy and the Risk of Conflict Over Taiwan (2024).