Winter 2025

The Role of Government: Time to Get Serious

Critical National Infrastructure – CNI — is easy to talk about but surprisingly hard to define. What should it mean in practice? And how do we decide what to do about it?

The UK Government’s online advice sets out 13 sectors of Critical National Infrastructure, from chemicals to food production. These deliver essential services – so failure in these areas could lead to potential loss of life. That seems a clear line to draw.

But the advice then hedges its bets: the definition of CNI should also be ‘taking into account significant economic or social impacts, and/or national security, defence of the functioning of the state’.

Within this wider context the protection of the digital systems which support financial networks and internet against aggressive cyber-attacks is also included in CNI. So, in today’s online economy the question arises whether there is much activity that is not potentially covered by this definition of CNI. And given this, how do we decide where to focus, given that all protection has a cost.

It is now over two decades since the world’s digital networks became pervasive. In the early days of the Internet, it was said that grenades dropped down manholes covering key data exchanges in just one or cities could have crippled the internet. Physical protection of cables and junctions is now taken much more seriously, and there is more redundancy within physical systems.

But the problem of preparing for unknown threats remains challenging. A lot of money was spent in 1998/99 in countries including the UK to protect against the so-called Millenium Bug, potentially neutralising computer systems that could not handle the year 2000. Ministers discussed the issue regularly, businesses prepared contingency plans and there was a state of high readiness over the 1999/2000 New Year. Nothing happened in the UK at midnight on 31 December; and nothing much happened in other countries where preparations were taken much less seriously. Was this money and time nonetheless well spent, or a wild goose chase that benefitted only the IT consultants? Easier to judge after the event than before.

The need to manage the costs of precautions is real, so as not to overload business with security costs their competitors do not have to absorb. Very often the specific issue for an individual firm will be how best to maintain a sufficient level of deterrence.

By analogy with home security a single lock can often be opened with a piece of plastic; a double lock and bolt might yield to a crowbar; four frame bolts and a metal reinforced door would need a battering ram. How much is enough to make potential cyber criminals look elsewhere? And how quickly does this change over time as technology develops further? Businesses have to weigh up these risks with the information available to them.

These trade-offs are less straightforward for public authorities and governments, with responsibility for the integrity of the infrastructure on which every business and individual relies. The choice of priority areas for protection is inevitably based on limited information and uncertain future projections.

Spending scarce taxpayers’ money on preparations that may never be used is not always easy to justify. Moreover, developing plans and exercises are easier and cheaper to organise than building stockpiles of key equipment, or maintaining redundant capacity in organisations so that they can be fully ready for emergency response.

It is also easy to become complacent about the resilience of existing plans. The UK authorities were happy with their planning for a pandemic before 2020; so long as it was a flu pandemic, on which most of those plans were based. After the difficulties experienced in responding to the Covid pandemic the construction of purpose-built vaccine facilities in the UK ready to scale up production in an emergency was proposed. But the high costs involved led to a decision not to do so, and instead to accept the accompanying risk to supplies in a future medical emergency.

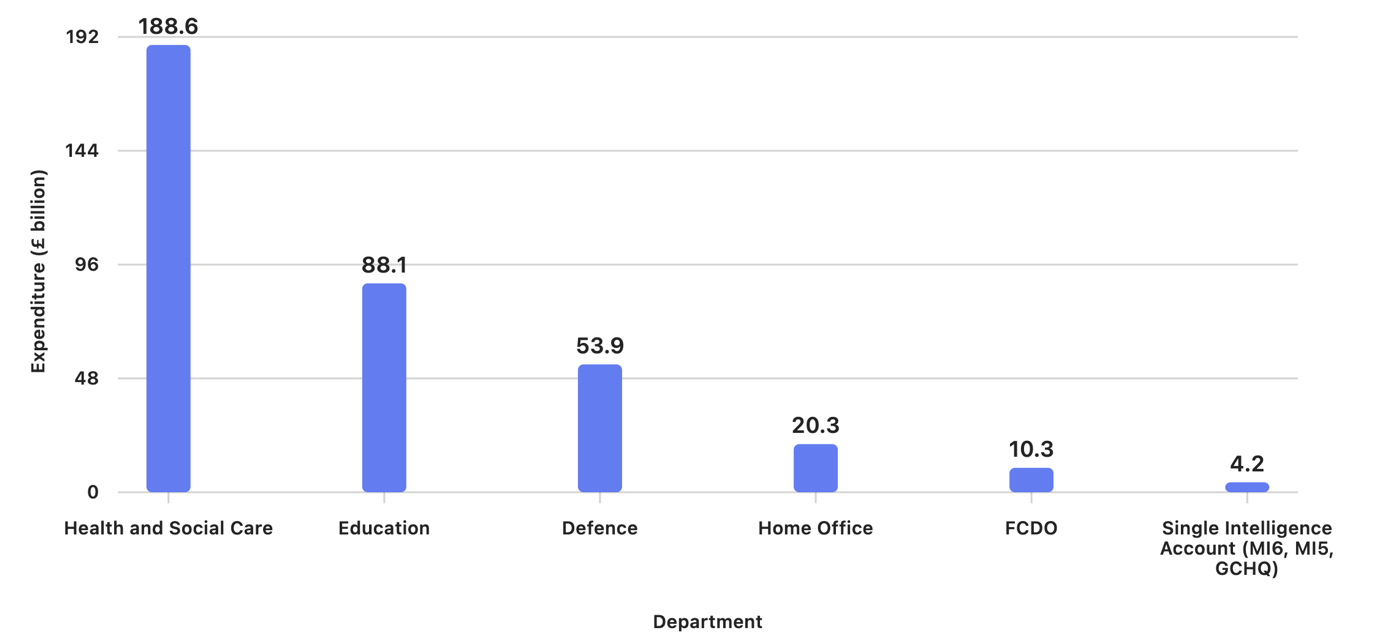

Source: UK Government

Similarly, it is hard to find public or private funds for long-term investment in energy grids, transport infrastructure or food and medicine stockpiles. After the Soviet blockade of west Berlin and the subsequent Airlift of supplies in 1948/49, West Berlin kept a year’s stock of food, fuel and other essentials in storage for four decades to deter any repetition of the blockade. The stockpile was partly funded by tax breaks and support from the West German government, in the political context of the Cold War.

Today some European governments are encouraging households to hold limited stocks of food and key supplies; the cost and complexity of providing this support centrally is seen as prohibitive. In the UK there is as yet little appetite for funding civil defence systems on the scale that existed throughout the postwar decades until the 1990s, and which provided some regional resilience in the event of nuclear or other attack.

So, risk is rising. Voters current preference seems to be for less rather than more taxation to pay for CNI, coupled with a hope that nothing too bad actually happens. Governments will maintain a high CNI wall around obvious national security/defence assets, but do not have the resources needed to extend these to daily life. The default position on many CNI threats seems to be education of the private sector and households to potential threats, with access to advice online. The problem with this approach is that if there is a failure of critical infrastructure it is too late to pay the premium for more CNI protection.

And there is a further twist. We tend to think of CNI as national. But we can be critically affected by crime or catastrophe elsewhere. Earthquake in Japan, war in Ukraine… but also interruptions to power supply in the many countries which form part of the UK’s business supply chain.

There is critical global infrastructure too. Protecting undersea cables, aviation and maritime supply routes, preventing cyber-attacks overseas which impact on UK digital systems or software, exchanging reliable technical information eg on pandemics in real time all require cross border and international cooperation.

In addition, there remain the longer-term challenges of climate change, population displacements from war or natural disaster, terrorism, action against criminal gangs, drugs, money laundering, global health and vaccination campaigns. These can all have immediate and severe national consequences. Managing these shared threats has until recently led to widespread support for the international organisations and independent agencies able to coordinate an effective response.

Recent years have seen moves away from a cooperative model, with the G7, G20, UN Agencies, and multilateral aid programmes all less well-resourced and less effective than in the past. These bodies are part of our international security policy which cannot be replaced at national level. If we choose to stop funding them to do this work how much extra risk are we running?

I believe we should spend more time reviewing the range of risks to all forms of CNI, in the context of our wider vulnerability in a low trust world. We will not like what we see. There is less consensus on shared interests, and more disruptive state and non-state actors able to pose a threat. But at least we can be clearer about the cost and risks of the choices we make, and the consequences of those choices for our future security and prosperity.

How we best to achieve the national consensus we need requires thought, and discussion. One way forward would be for a Parliamentary committee to engage regularly with all the issues around resilience in the digital age, review new information on emerging risks, and compare the UK’s state of CNI protection with that of other comparable countries.

Parliament’s work could form the basis of wider discussion across the UK, with the goal of reaching shared agreement on a new partnership between Government and civil society to ensure key national CNI is adequately protected, while local communities are empowered to mitigate the impact of food, fuel or medicine disruption on their citizens.

Decisions on CNI funding and organisation must continue to evolve in response to the threats we face. But these decisions can only be sustained with a democratic acceptance that maintaining national resilience for critical infrastructure and services is now everyone’s business. Over to you Parliament to lead the debate and focus minds on how best to meet the challenges ahead.

Martin Donnelly, is a former Permanent Secretary of the UK Business and Trade Departments, and former President of Boeing Europe. He advises the UK Foreign Office on growth and global issues.