Winter 2025

Europe’s Search for Resilience

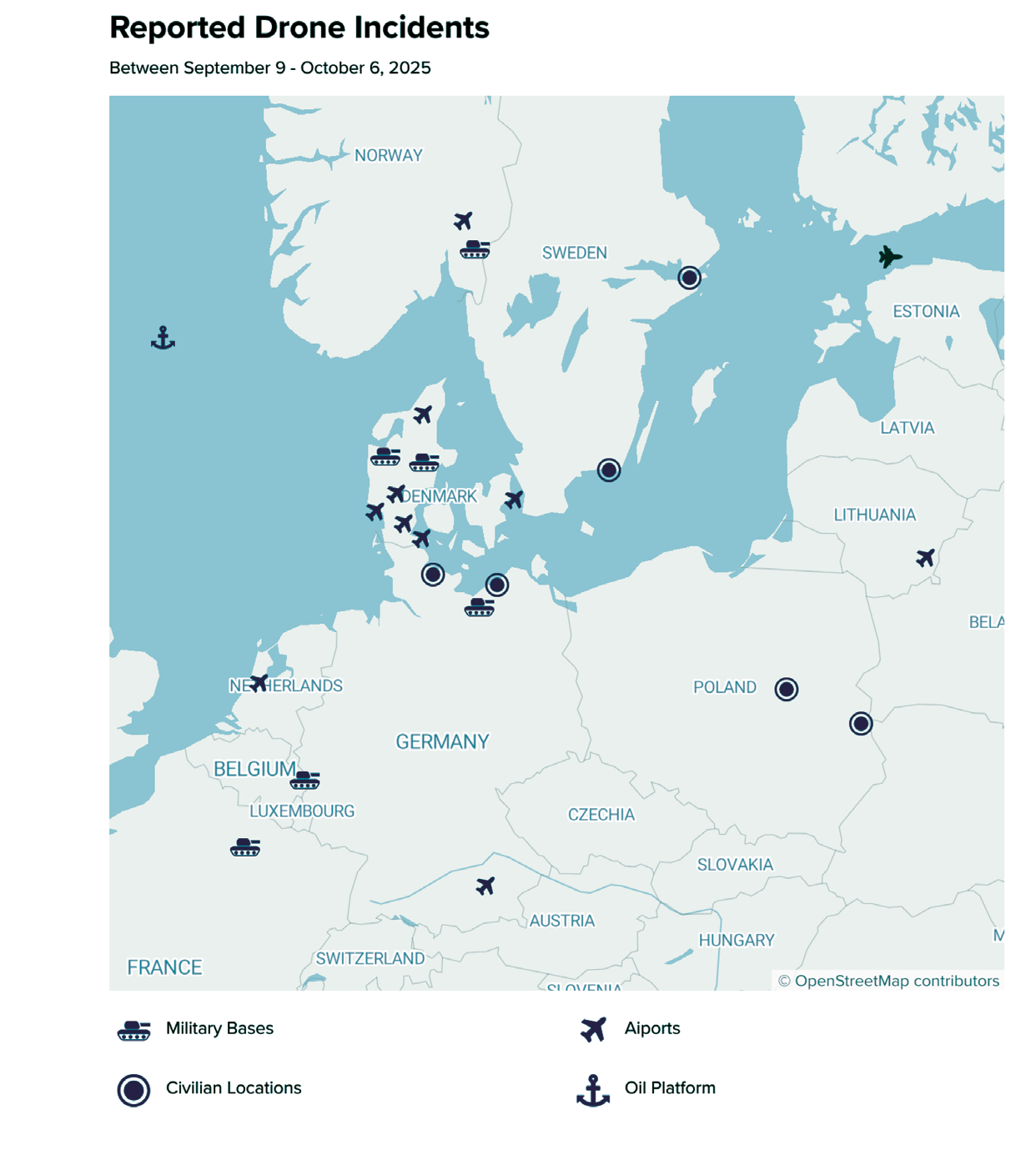

Within the course of just a few days this autumn, Lithuanian authorities had to close Vilnius Airport six times – because balloons flying in from Belarus were affecting air traffic. That was shortly after drones forced the airports in Copenhagen and Munich to temporarily close. The shadow fleet, meanwhile, continues to sail through the Baltic Sea, each voyage carrying the risk of a severe oil spill in the fragile mini ocean.

And all around the region, new forms of geopolitical harm are arriving at an increasingly rapid pace. For countries near Russia (and not just them), 2025 has made life even more perilous. The Kremlin, though, is unfazed by revelations that it’s behind the mischief. Cigarette smuggling from Belarus to Lithuania and Poland had long been a scourge. In 2021, for example, the Polish Border Guard intercepted a remarkable 104 million cigarettes that were being smuggled into the country from Belarus, the broadcaster RMF has reported.

That year, Belarusian authorities began causing trouble of a completely different kind at Belarus’s borders with Latvia, Lithuania and Poland: it suddenly began issuing lots of tourist visas to people from countries like Iraq and Afghanistan. The implicit promise was that once they arrived in Belarus, the local authorities would help them get to the country’s borders with the three EU member states (and Schengen members). There they would claim asylum.

It was a cunning plot, and it worked. Suddenly, thousands of asylum seekers arrived at the three countries’ borders, overwhelming the countries’ abilities to keep the crossings safe. What’s more, the mass arrivals unleashed a heated debate in the three nations and across the EU about whether some of the migrants could be refused entry. Belarusian ruler Aleksandr Lukashenko’s régime had set out to destabilise its neighbours and the EU (and NATO, for that matter) with non-military means, and they had succeeded

A few years earlier, Russia had launched a similar scheme at its borders with Norway and Finland, and when Belarus – one of Moscow’s closest allies – launched its scheme, Russia duly helped migrants already in Russia to get to Belarus to join the Minsk-led destabilisation initiative.

To secure their borders with Belarus, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland quickly built fences or walls. That caused the smuggling of contraband to plummet, too: in 2022, a mere 18.7 million cigarettes were intercepted by the Polish authorities. Criminals, though, are enterprising. To get their cigarettes into Lithuania, they have recently taken to sending GPS-enabled parcels attached to large balloons – and the Belarusian authorities have not stopped them. In fact, Minsk appears to have quite relished seeing criminals causing disruption on EU and NATO territory.

At the end of October, after the shocking string of incursions that forced Vilnius Airport to close several times, Lithuania’s new prime minister, Inga Ruginiene, announced that her country would start shooting down the balloons. “In this way, we are sending a signal to Belarus and saying that no hybrid attack will be tolerated here, and we will take all the strictest measures to stop such attacks,” she declared.

That ought to put an end to the subversive balloons. But balloons are not the only new grey-zone activity afflicting countries around Europe – quite the opposite. Ever since its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022,

Russia – occasionally aided by Belarus – has dramatically ramped up its grey-zone activities around Europe. (Grey- zone aggression is sometimes referred by as hybrid aggression or hybrid warfare.) It is as if the invasion has caused the Kremlin’s mask to slip. Before the invasion, Putin and his entourage were still eager for Russia to be considered a respectable country. Since then, they have had no such pretences or desires.

Source: Map: Sarah Krajewski/Hiene Brekke/Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA)"

Consider the arson that burnt down Poland’s largest shopping mall in May 2024. A year later, Polish leaders declared that evidence showed Russia was behind the attack, which had been carried out by criminals recruited for the purpose. Just before the Warsaw arson attack, arsonists set fire to an IKEA store in Lithuania; they later turned out to be Ukrainians recruited by Russia. In the weeks before Germany’s Bundestag elections in February 2025, hundreds of cars were sabotaged in what was designed to look like the work of supporters of the Greens.

Instead, the perpetrators turned out to be small-time criminals who had been recruited by a Russian on Viber for a payment of 100 euros per car. On 1 November, three Bulgarians were convicted in a French court for a string of crimes designed to destabilise the country: they had defaced Jewish sites and placed pig’s heads in front of a mosque. ‘Even the defence lawyers openly admitted that “we suspect” Moscow’s hand,’ the BBC reported.

Drones have buzzed defence manufacturers’ facilities. Around Easter 2025, perpetrators sabotaged some 30 telecoms towers in Sweden; the fact that they stole nothing suggests they were not mere criminals. There have been mysterious break-ins into Swedish and Finnish water plants.

And that’s not even mentioning the GPS interference. During the first nine months of the year, Sweden alone received 733 reports concerning airliners affected by GPS interference while flying in Swedish airspace.

That’s up from a total of 55 such incidents during the whole of 2023. The situation is similar in the other Baltic Sea countries, whose authorities have also been able to identify the sources: devices in the Russian cities of Kaliningrad, St Petersburg, Smolensk and Rostov.

Or the shadow fleet, whose unsafe vessels carrying large amounts of oil sail through the Baltic Sea several times each day, typically under the flag of nations that would be entirely unable to intervene (as required by flag states) in case of an accident. Indeed, some of the vessels appear to have secondary duties too: harm undersea infrastructure, say, or serve as drone platforms.

Indeed, any part of daily life in Europe’s free and open societies is vulnerable to harm by Russian government entities or the gig workers they increasingly commission to carry out grey-zone acts. Precisely because European countries are free and open, their authorities can’t be everywhere, all the time, nor would that be desirable.

Then one must consider the convenience trap (my term): the more convenient digital tools make our lives, the more vulnerable our societies become. If an enemy wanted to harm, say, Mali by targeting internet connectivity, it could quickly realise it was a bad idea since only 35 percent of Malians have internet access.

Targeting internet connectivity in the Baltic Sea region is infinitely more attractive.

Sweden’s National Cyber Security Centre reports that geopolitics-linked DDOS attacks against the Nordic and Baltic countries increased in 2024. (DDOS attacks are a form of cyber-attack.)

What is more, the close links Europe formed with Russia after the end of the Cold War – links intended to showcase a harmonious relationship and contribute to more prosperity — are now a vulnerability. Nord Stream is, of course, no more, but Western authorities must worry about the subversive nature of Russian money in their countries; about properties and companies owned by Russians; about Russian nationals themselves, who these days have often acquired citizenship in a European country and can’t be expelled.

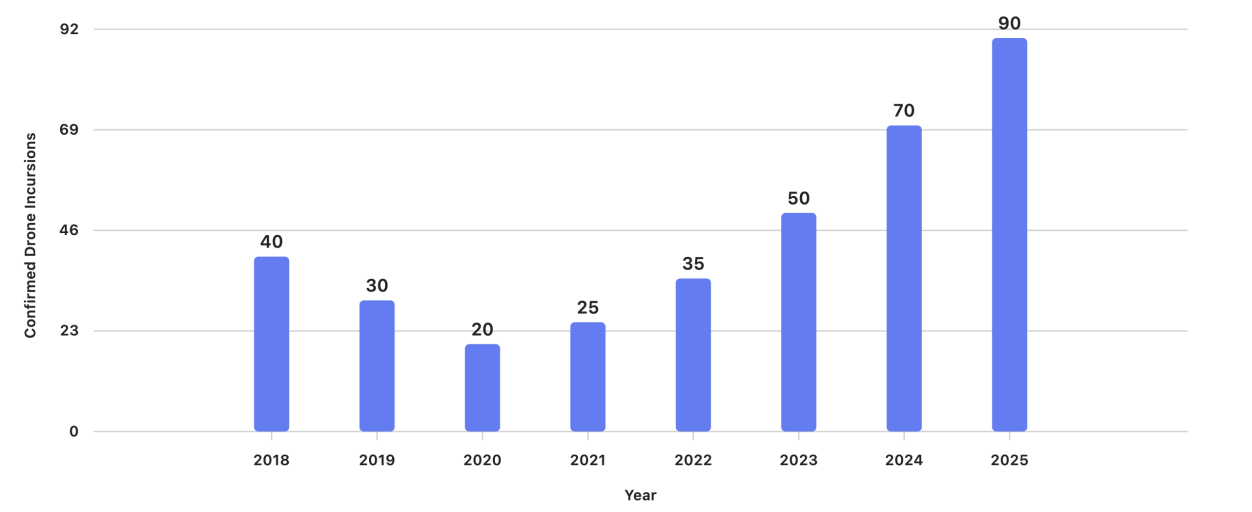

Source: (Data accurate to 10/11/2025), Source Map: UK Airprox Board (UKAB), EASA (European Union Aviation Safety Agency), Eurocontrol and incident-specific reports from major disruptions (e.g. Gatwick 2018, Munich and Vilnius 2025) published by national aviation authorities. These sources do not publish a single consolidated dataset, so the numbers represent confirmed airport incursions extracted form these reports, not all drone sighting or Airprox events.

In the early days, weeks and months after the invasion of Ukraine, Western governments did not realise what a fork in the road the invasion was, and how could they? Politicians do not have the benefit of hindsight. But since then, they and many others have realised that by invading Ukraine, Russia signalled to the whole world that it no longer values respectability. That makes it likely, practically inevitable, that the Kremlin will continue to expand its grey-zone aggression and that it will continue to invent new forms of it.

That, in turn, makes it imperative for European and other Western governments to include the private sector and the wider public in their preparedness planning in whatever ways possible. They can practise grey- zone scenarios with key companies big and small. The exercises do not have to be perfect; it is better to exercise in a modest fashion than not to exercise at all.

A few countries including Sweden and the Czech Republic are already trying. The number of countries that have designed information leaflets for the public – and are disseminating them – is growing fast, with Poland among the more recent entries. Norway has a Self-Preparedness Week that reminds Norwegians of their responsibilities before and during crises and teaches them how to prepare.

Resilience alone will not defeat the ugly, unethical and mostly illegal grey-zone aggression, but it can blunt its force. And in the Baltic Sea, the coastal states have demonstrated that quiet persistence can make a dramatic difference. Every day, the different nations now patrol their waters on their own and through their Baltic Sentry collaboration, which operates under NATO command. There have been no suspicious cable incidents since the beginning of the year. That does not mean the persistent patrolling will prevent all deliberate harm to cables, but the quiet this year follows three years of turbulence.

In my book The Defender’s Dilemma, I outlined the depressing reality facing liberal democracies targeted by grey-zone aggression: it is a profound defender’s dilemma. But as I also outlined in the book, there are steps such countries can take that are neither illegal nor unethical; grey-zone exercises, resilience leaflets and patrolling of undersea cables are only a few of the actions available.

One measure I recommended that can easily be implemented is selective cancellation of visas for family members of officials involved in aggression against European countries. Traditionally, Western countries have been loath to cancel visas of people who are merely family members of various perpetrators, not perpetrators themselves. But a visa is a privilege, not a right. At times of their choosing, Western governments could – in coordination with one another – cancel the visas of one, two, three or four family members of Russian officials at the very top and further down the chain. A nuclear option, which would still be legal, would be to cancel all visas issued to Russian nationals.

Another measure has been tried once, after the Novichok attacks in Salisbury, and could be used again: the temporary throttling of funds going to and from Russian accounts. This would require the cooperation of Western banks but given that the financial sector too has been targeted by Russian hackers, assisting the government should not be an onerous task.

Western governments could also name the Russian nationals who own properties, bank accounts or companies, or a combination thereof, in Western countries. This information is publicly available, but not always easy to find. Exposing the duplicitousness of Russians who enjoy the benefits of Western democracies while doing nothing to stop Russian aggression is not just a useful response to grey-zone aggression but also a useful step towards uncovering murky money transfers and ownership arrangements.

Most importantly, Western countries can build national resilience. It’s non-aggressive, non-escalatory and helps thwart attacks. For national resilience to be successful, it must involve the whole nation: not just the government but also the private sector, the third sector and the wider public. A decade ago, societal resilience was a priority for the fewest countries in the world: Finland, Singapore and a few others. Since then, Sweden – the Cold War master of societal resilience – has made great strides, and so have more recent entrants into the field like Estonia, Latvia and Poland. Taiwan, too, has ramped up its resilience efforts. Sweden’s In Case of Crisis or War preparedness leaflet has been adopted and adapted by a growing number of countries.

In my book, I proposed resilience training for teenagers as a mandatory effort between the penultimate and final years of secondary education. That idea is gaining traction as the geopolitical situation continues to deteriorate (and the risk of further pandemics is obvious to all). Resilience training could also be made available to all members of society; it should lead to accreditation so graduates can join government efforts during crises and emergencies.

Education is, in fact, central to building societal resilience, and countries can experiment. Taiwan’s Zero Day Attack is a brilliant television series – and brilliant public education about threats facing the country. Now is the time to experiment and invent.

Elisabeth Braw is a Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council, Senior Associate Fellow at the European Leadership Network, and a member of GALLOS Technologies’ advisory board. She is the author of The Defender’s Dilemma: Identifying and Deterring Gray-zone Aggression (2022) and Goodbye, Globalization (Yale University Press, 2024).