Winter 2018

Ethical Migration Policies for Harsh Times

Globalization has opened up two deepening rifts across Western societies. One is spatial, between the booming metropolis and broken provincial towns and cities. The other is the new class divide, between the college-educated who are bene ting from rising demand for skill, and the less-educated whose manual skills are becoming less valuable. Nothing has been done to reverse these widening rifts. The attitude of the metropolitan educated to the provinces is illustrated by one of its most astute chroniclers, Janan Ganesh: ‘like being shackled to a corpse’. This phrase captures both a rationale for neglect – a corpse cannot be revived – and the underlying sentiment of brutal contempt. Understandably, the provincial less-educated have become increasingly angry. Brexit, Trump, AfD, the new coalition government in Italy, all reflect the resulting mass mutinies.

The epicentre of this mutiny is about migration and refugees: the mutineers regard their own interests as being sacrificed in favour of more fashionable ‘minorities’. Pictures of the disorderly influx of Syrian refugees into Germany beneath the phrase ‘Take back control’ were probably decisive in the Brexit campaign. In response, the educated metropolitans have seized on the tempting taunt of racism and bigotry: opponents of open borders are ‘deplorable’. This response is psychologically attractive, since those who use it implicitly assert their own moral superiority. For the mutineers this compounds the original offence: our societies are rapidly polarizing into mutual hatreds.

Meanwhile, migration and refugee policies have become chaotic: unmoored from any ethical principles. Policy lurches reflect the power struggle between the mutineers who want to close borders and the educated metropolitans who want to open them. Angela Merkel, responding to rapidly changing opinion polls, first unilaterally opened Europe’s borders, then unilaterally closed them through a privately brokered deal with President Erdogan. Similarly, President Macron publicly castigated the Italian Government for refusing to disembark irregular migrants crossing the Mediterranean, but promptly refused to let a French boat full of them dock in France. In restoring ethical sense to public policies, a useful concept is the duty of rescue. The classic context in which such a duty can be invoked is a passer-by who sees a child drowning in a pond. The duty to help is unambiguous: it arises not from any rights of the child, but directly from what it means to be human. But what is the extent of the duty? Its core is to get the child out of the pond, get it dry, and return it home: it does not extend to providing the child with an education. I apply the concept first to aspiring African migrants and then to refugees.Ethical migration policies

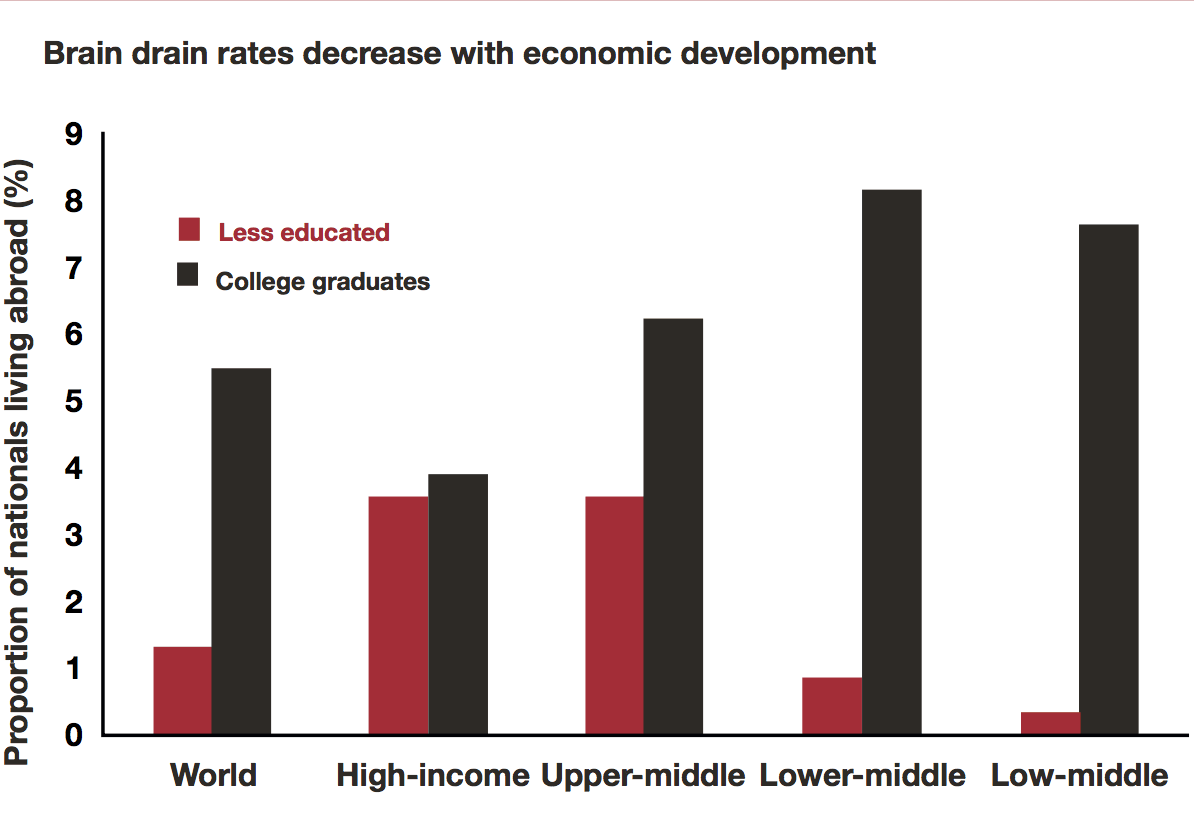

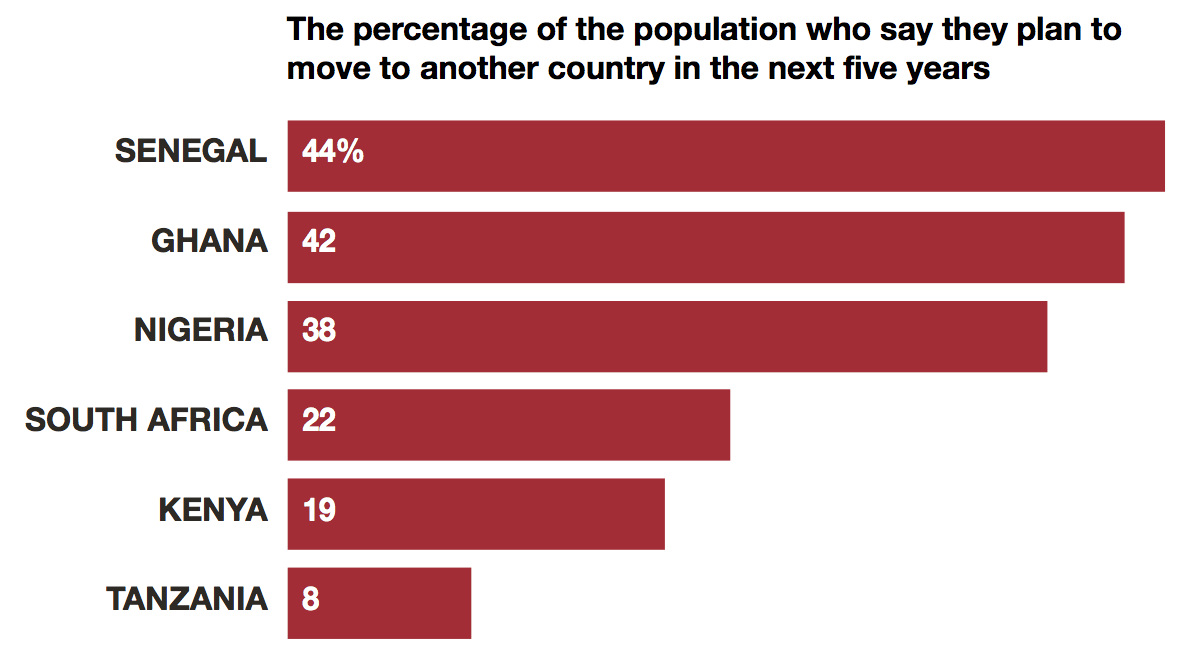

The immediate analogy to the child in the pond is, of course, the aspiring migrant drowning in the Mediterranean. As with the child, the responsibility of the bystander is to get the person to safety and restore them to their home. But there is an important dimension missing from the analogy. The person is drowning because of the hope of irregular entry to Europe: the danger is traceable to a temptation that has proved irresistible. It is as if the child has jumped into the pond in the hope of seizing a golden ball thrown in by the bystander. Had the bystander indeed thrown the ball, he would have breached a clear moral responsibility: ‘thou shall not tempt’. In failing to enforce border controls, Europe has been guilty of breaching this injunction. The only ethical choices facing Europe on its border policies are fully open borders, so that aspiring migrants can enter by safe regular means, or enforced borders by which irregular migrants are saved from the sea but returned to Africa. Of these two options, the former, favoured by the metropolitan educated, turns out to be unethical because it breaches a different aspect of the duty of rescue: it entrenches the narrative among aspiring young Africans that hope lies in emigration. In the phrase that has become common among West African youth: ‘Europe or death’. Ghana, Senegal, and Morocco, three of the countries from which many of the migrants are coming, are each well- governed countries whose economies are growing rapidly. Yet there is nothing that their governments can do to negate the reality that in emigrating to Europe, a well-educated young man would quite possibly be much better off. But what would be the consequences for the continent if such people permanently leave? Evidently, their countries lose the very people on which their future depends. The only viable narrative for Africa is that the region is going to catch up, and that its young people have a collective mission to achieve this goal. Europe’s role is to help make that narrative credible, not to undermine it by encouraging the brightest and the best to leave. The duty of rescue, applied to African youth, is not to save them individually from their continent, but to lift their collective despair of their prospects in their continent. How can Europe meet this ethical duty?

Source: World of Labor

Source: Pew Centre, Spring 2017 Global Attitudes Survey

So how can Western public policy best assist this process? The key vehicles are our Development Finance Institutions (DFI), such as International Finance Corporation (IFC), Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) and Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) . All three are currently being scaled up, as aid donors realize that their priorities need to shift from encouraging social spending to encouraging jobs. The firms that pioneer a sector in a poor country can generate huge social benefits: the $30bn Bangladeshi garments industry, which has transformed the status of young women in the society, was started by one foreign firm from which local entrepreneurs learnt. DFIs can potentially use their new resources to encourage more Western firms to become pioneers, covering some of the risks, and bearing the costs of first-mover disadvantage such as the need to train workers in unfamiliar skills. Our NGOs need to get behind this process. To date they have been ideologically hostile to foreign business, threatening firms with reputational damage for ‘exploitation’. They need to be shamed out of such self-indulgent moral grandstanding.

Some migration to Europe can help in this process of catching up, but it is circular migration. As long as the enforced legal position is unambiguous, young Africans can usefully come to Europe to acquire education and skills in the clear knowledge that they will return home after a specified period. This would complement the circular migration of the unskilled to the Gulf, which provides a valuable safety net for poor households.Ethical refugee policies

In collaboration with Alex Betts, Director of Oxford’s Refugee Studies Centre, I worked on the Syrian refugee crisis. We were sufficiently shocked by the failures of Western public policy to meet the duty of rescue that were driven to write Refuge: Transforming a Broken Refugee System (2017), a clarion call to change. Return to the analogy of the child drowning in the pond. As with the child, the flight of a refugee family from their home due to spreading violence and disorder triggers an empathy with their plight that almost everyone can feel: as fellow human beings, we recognize a duty to help. As with the child and the aspiring migrant, we next need to ascertain our core duty: in respect of refugees: it is to try to restore a semblance of normality. In terms of physical location, it is likely to be best met by providing a proximate and familiar haven where a community can remain together until return becomes feasible, or the refugee can integrate into the society of the haven. In respect of lifestyle, the task is to restore the basic autonomy and dignity that comes from being able to earn a living. These physical and lifestyle conditions are indeed what most refugees seek. Around 85 percent go to proximate regional havens, often culturally familiar, where the threads of normal life can be pieced together. By definition, refugees are not aspirational migrants: they are the people who chose to stay at home until home became unsafe. Within the regional havens, most refugees bypass the camps and free food provided by UNHCR, preferring to go to the cities, where they can find irregular, extra-legal work.During the Syrian refugee crisis, which began in 2011, the international community has neglected both the physical and the lifestyle conditions that constitute the duty of rescue towards refugees. In respect of physical location of havens, the prime duty of high-income countries was to make it politically viable for the governments bordering Syria to keep their borders open. Yet Jordan, Turkey and Lebanon were left to bear the financial burden themselves, leading them periodically to close their borders. In respect of the lifestyle offered to refugees, UNHCR has ignored the need to restore autonomy: its model is camps in which people are housed and fed for free. In response to our emphasis upon the need to provide jobs, it objected ‘we are not a jobs agency’. There lies the problem: UNHCR is not equipped to meet the needs of refugees.

The two failures interacted. Because most refugees headed for the cities, where they were willing to undercut locals at the bottom of the irregular jobs market, they swiftly became unpopular. In response, governments felt it politically necessary, periodically to close their borders. Meanwhile, European NGOs compounded the failure by focusing exclusively on the entirely second-order issue of bringing a small minority of refugees to Europe.As with aspiring migrants, what was needed was to bring jobs to people rather than people to jobs. Typically, refugee families were unsuited both to the cultural shock of Europe and to the high hurdles of skill and language needed to get a job. Germany, with its highly regulated and skill-intensive labour market, was particularly ill-suited. When Germany’s borders were briefly opened, the result was a highly selective influx: whereas the demographic profile of refugees in the regional havens mirrored that of Syria, those in Germany were predominantly educated young men. Alex and I estimated that whereas only around 5% of the Syrian population moved to Germany, between a third and a half of those Syrians with a university education migrated there. Since all of them embarked from regional safe havens, none had been in mortal danger: this was predominantly aspirational migration rather than refugee flight.

So, what should have happened? As above, our firms should have been encouraged and financed to bring jobs to the regional havens. German firms had been creating jobs in Turkey for many years and so it would have been entirely feasible. The European Commission assisted by giving Jordan ten-year market access to the EU. Again, NGOs were counterproductive, seething with antagonism to ‘sweatshops’, as if a formal job with a European firm in Jordan would be anything other than an improvement on previous life in the impoverished economy of Syria. The Government of Jordan agreed to what became known as the Jordan Compact: it offered up to 200,000 work permits for refugees, as long as new jobs came in, shared 70–30 between refugees and locals. The Compact is now becoming the new model for refugees elsewhere.

The implication

Europe and North America have duties of rescue towards both young Africans and refugees. This is a proposition on which our educated metropolitans are rightly passionate. But while their preferred solution of open borders may confer a satisfying frisson of moral self-righteousness, it is, on proper reflection, an insult to the serious nature of the problem. Properly understood, our duties of rescue can be shared and met equally by educated metropolitans and their poorer and less educated provincial fellow-citizens. That these duties have become divisive is cruel, avoidable and frustrates effectiveness. In meeting them more effectively than hitherto, the key actors will be our firms, deploying their ability to harness globalization so as to bring jobs to the people most in need of them. In turn, this contributes to restoring moral purpose to business. Contrary to Milton Friedman, the sole purpose of business is not the pursuit of profit; it is to be the primary organizational vehicle for the proper goals and duties of our societies.Paul Collier is Professor of Economics and Public Policy at the Blavatnik School of Government, Oxford University. He is the author of The Future of Capitalism: Facing the New Anxieties.