Winter 2018

Growing Friction for Cross Border Investment

In June of this year, Qualcomm of the US announced it was dropping a bid worth $44bn for the Dutch semiconductor company, NXP. The deal — originally announced in October 2016 — had failed to receive regulatory consent.

So far, so normal. It is not uncommon for large cross-border takeovers to face regulatory friction — and sometimes even to get the outright “no”.

But in this case, the circumstances were unusual. The deal didn’t fail because it encountered US concerns or conventional-style Brussels opposition. No the black-ball came from the other side of the world — all the way from China.

The reasoning was obscure: officials in Beijing indicated their objections to the US tech company’s deal centred on anti-trust issues. But in practice, the rejection was part of wider trade wrangling between the US and China, over patents and the status of ZTE, a Chinese telecoms maker the Trump administration had just threatened to cold-shoulder from US markets.

Not that the reasoning mattered much to Qualcomm. China’s opposition was enough to torpedo the transaction. The company needed Beijing’s approval because China accounted for 44 per cent of its sales last year.

Qualcomm’s failed deal is just one sign of how geopolitical tensions are weighing on cross-border M&A deals as countries become more sceptical about inward investment. “It’s not so long ago that developed countries thought it was smart to throw open the door to foreign investors,” says one analyst. “Now the mood has changed, and this more suspicious and sceptical atmosphere is kind of feeding off itself.”

This is beginning to be felt in the M&A statistics. Global cross-border volumes were down 30 per cent last year on their $1.4tn peak in 2015, according to Dealogic, although there has been a recovery this year.

](https://montroseassociates.biz/images/uploads/7.png)

Source: lexology.com

And while the decline clearly reflects many wider economic and market factors, one big influence was fewer Chinese outbound mergers and takeovers. Volumes peaked in 2016 at $98bn, then halved the following year to $45bn. This year there has been some recovery, but only back up to $58bn in 2018 to date. Nor are Chinese the only ones retrenching. From their peaks in 2015, both European and US overseas acquirers have also reined in their forays overseas.

The one partial exception is the UK, where the uncertainties of Brexit have led to some opportunistic activity. US deals into the UK have continued to rise, hitting $87bn in the year to date against $70bn in 2016, according to Dealogic. Chinese acquirers have been busy too, with volumes climbing to $21bn last year from a base of $3bn in 2015.

But there is no doubt that wariness about China is driving a more politicised approach to vetting M&A and foreign direct investment deals. “There is a general impression that China is rising on all fronts , and the question is how to deal with that,” says Philippe Le Corre, a China specialist and senior fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School. “Most countries don’t know how to react.”

The west has come to rue the bargain it struck with Beijing that allowed China into the western trading system in 2001, without opening its markets to western access. It is a view that has sharpened as China has veered back towards a more autocratic system under its present leader, Xi Jinping. This dashed hopes that growing trade would lead the Middle Kingdom, if not towards democracy then at least to acceptance of a rules-based international order.

According to Michael Tory, the boss at investment firm Ondra Partners, the catalyst for the change was the release in 2015 of China’s “2025 Made in China” policy, which seeks — through the expedient of hosing subsidies at state-owned enterprises — to make China dominant in global high tech manufacturing.

“It made people look at China in a different way; as a strategic competitor,” says Tory. “So then you say what’s the right way to deal with someone who’s not a partner but a competitor, and that makes you more cautious.”

The US has long been hawkish about Chinese acquisitions, with the Committee on Foreign Investment in the US (C us) intervening to strike down investments ranging from the tech sector to oil and gas.

But these concerns are widening. In August this year, Donald Trump signed a bill that would bar US government contractors from using any equipment produced by the Chinese tech firms, Huawei and ZTE. The move ratchets up a further notch the dispute that riled Beijing into the tit-for-tat zapping of Qualcomm’s merger.

Nor is America alone in tightening the screws on scrutiny. Europe has shown willingness to impose tougher restrictions. Hitherto seen as a soft touch because of the EU’s relative lack of security-related rules, Chinese bidders and contractors are now encountering fiercer political resistance.

France has a tradition of using ambiguity in its laws to impose unusual national security designations on proposed deals. It even pinned the label on yoghurt maker Danone in 2005, inserting it on an official list of “strategic” (i.e. paws-off) assets to widespread mockery. But protectionist sentiment has grown in Germany since the controversial Chinese takeover of Kuka, an industrial robotics firm, in May 2016.

In August, the German government announced it would take on new powers to block foreign investments, significantly lowering the threshold of deals that could be subject to ministerial veto. This followed a series of high profile interventions in Chinese deals. In July, Berlin directed the German state development bank KfW to take a 20 per cent stake in 50Hertz, a high-voltage power network operator, to pre-empt the stake’s acquisition by a Chinese state investor. Soon afterwards, a Chinese company, Yantai Taihai, withdrew its bid for Leifeld Metal Spinning, a small German machine tool manufacturer that specialises in materials for the aerospace and nuclear industries, after the government moved to block the deal. It would have been the first use of Germany’s foreign investment law to veto a mergers and acquisitions transaction.

Observers say that governments are sometimes sheltering behind national security considerations to impose a wider agenda. This can spill over into protectionism. “It’s easier to use a ‘respectable’ cover-all definition like national security if your real target is a specific country or region,” says one trade expert.

“It has a lot to do with reciprocity and market access,” says Gregor Irwin of the advisory firm Global Counsel. “Often the stated concern is about the acquisition of technology. But think about it: this is hardly new. Companies have been acquiring technology overseas since forever. The real worry is that China can outbid rivals for these technologies because it can also exploit them in China’s giant home market when others can’t. That is an unfair advantage.”

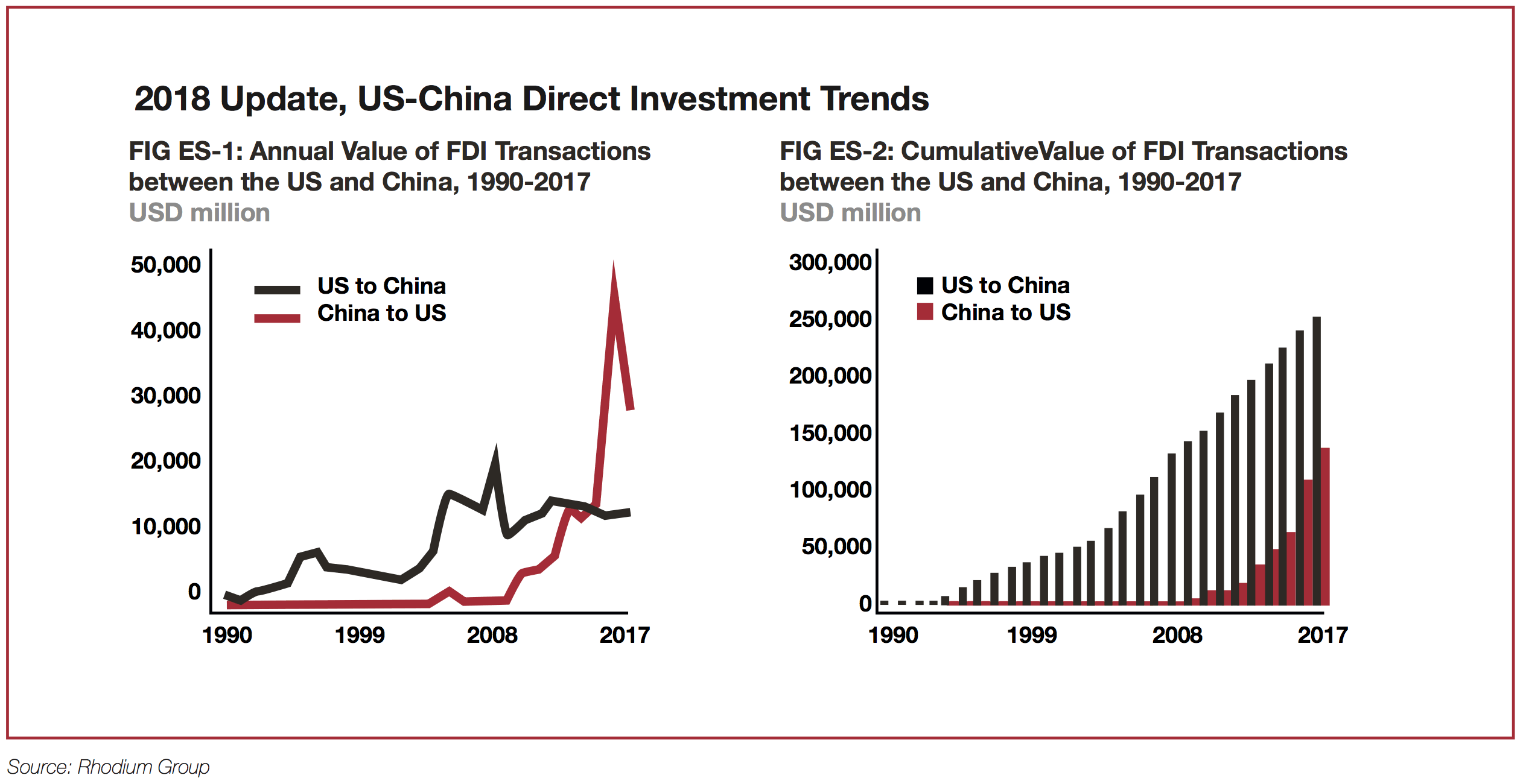

Source: Rhodium Group

So far there is only patchy evidence that security issues are politicising the wider anti-trust and merger review arena. In the US, the number of “second requests” issued to scrutinise transactions closely and the number of challenges have in fact declined slightly.

However, political concerns in the EU about the market power of (generally American) technology companies appear to have contributed to closer scrutiny of certain transactions — albeit without yet affecting the outcome.

Perhaps the biggest test may come in the UK, where Theresa May’s government is seeking to extend security carve outs, a move that many see as widening significantly the scope for political involvement in mergers.

The plans would require business owners to notify the government of any transaction that might trigger a host of potential national security risks. This applies not only to deals that involve takeovers, but could also be acquisitions of assets, intellectual property or large shareholdings. It reflects ministerial frustration about the government’s inability last year to call in the takeover of Imagination Technologies, a UK chipmaker, by Canyon Bridge because the latter was based in California. Canyon Bridge is backed by the Chinese state owned fund Yitai Capital.

The proposals have been criticised by Sir John Vickers, a former director-general of the Office of Fair Trading as “disproportionate in several respects, including the creation of a new regulatory régime, in parallel to the competition régime.. and the wide scope for business intervention in business transactions”.

Officials have suggested that the government could examine 200 cases under the new régime with about 50 subjected to intervention or blocking.

That’s a substantial subset of the total: there were only 811 foreign M&A acquisitions in the UK last year. Currently, only a handful of cases are referred to the Competition and Markets Authority each year, with rarely more than one being blocked on national security grounds. One concern is that ministers will use these measures to resist a Brexit related “fire sale” of British businesses.

Observers think such an event could pull the Theresa May’s government in two opposing directions. While ministers would not want to stand aside and see leading brands and businesses fall to foreign buyers, there would be an aversion to intervene at a time when Britain wanted to show it was open to new investment.

“Theresa May would be very nervous about doing anything that suggested Britain was somehow closed for business,” says Mats Persson, a trade expert at the accountancy firm EY.

Whatever happens in Britain, the world is entering a period of heightened friction for cross border investment. “Instead of a situation where there are constant incremental steps towards the opening up of markets, each country’s move to slide the door shut a bit is provoking others to follow suit,” says on City investor. “So the general direction is towards more restrictions, whether in trade or investment flows.”

Underlying it all is concern about the rise of China and how to ensure a level playing field for western investors, as well as the protection of sensitive and security related technologies. These are far from resolution.

“With developed countries, there’s generally confidence that both sides have a vested interest in fair conduct because of the web of interests they share,” says Michael Tory.

“The issue with new actors in international M&A is that you can’t rely on reciprocity to ensure fair behaviour. This means you have to be more selective about who you let the drawbridge down to.”

“We are at the start of a long cycle where international disagreements and tensions about trade and investment feed off one another and influence policy choices in countries in a protectionist direction” says Gregor Irwin, at Global Counsel.

Their impact on global investment flows remains uncertain. But as politicians focus more on domestic distributional issues, where global actors can easily be cast as the enemy, the prospect of tighter controls and diminished transactions must be seen as real.

Jonathan Ford is chief leader writer for the Financial Times