Resilience

Has Covid-19 Given the Planet a Second Chance?

December 2019 seems like a lifetime ago. At the time, I was on my way to Madrid to attend the latest round of UN climate talks, COP25, after receiving an invite to speak at an event on renewable energy.

It wasn’t the first time Good Energy was at COP after my team joined the historic Paris negotiations in 2015, witnessing first-hand the unique deal which brought together almost every country on earth. The joyous scenes in Paris were set in high contrast by the muted and disappointing atmosphere of Madrid. The climate emergency was not on show as leading nations sought to block progress, water down existing commitments, and the US stand was literally a closed door.

In the 12 months since Madrid, the world has changed beyond recognition. The political and economic impact of Covid is still being felt and its aftershocks will last for years. What remains the same is the urgency of cutting greenhouse gas emissions to safe levels and halting dangerous climate change.

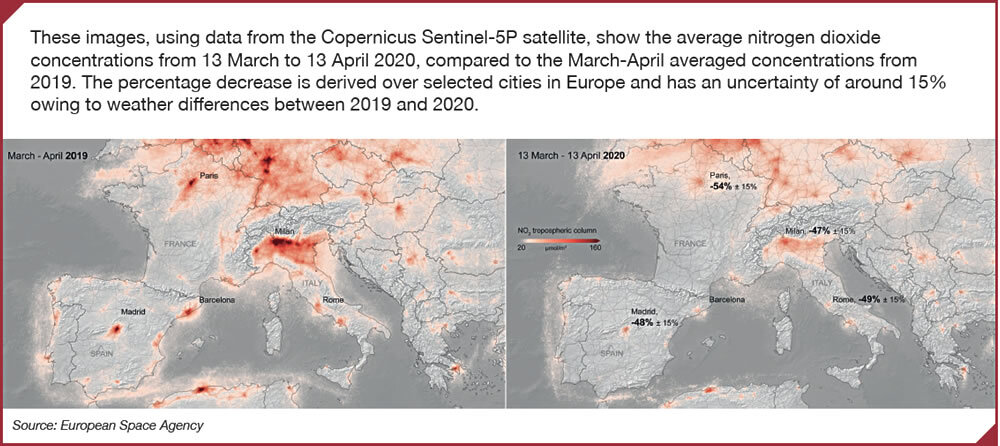

When the pandemic first wreaked havoc across the globe, some commentators were keen to see the potential upsides: cleaner air, renewed wildlife, and a chance to rethink how we do things. The terms ‘green recovery’ and ‘build back better’ became part of our lexicon. Within weeks of the global shutdown, multiple open letters appeared from business leaders, politicians, actors, and writers all calling for an economic recovery which prioritised sustainability and green energy.

These calls were backed up by polling which showed people didn’t want the economy to return to normal. The RSA in London conducted a survey in which only 9% of respondents wanted to completely go back to the way things were, with 51% saying they noticed cleaner air, and 40% feeling a stronger sense of community. A separate, global poll from Ipsos MORI in April found that 71% of people agreed that climate change was in the long-term as serious a crisis as Covid.

The challenge for government is to make that goodwill stick, and to turn it into a set of tangible policies which will have an impact. The task ahead of us remains as daunting as ever. The UN reported last November that global emissions would have to fall by 7.6% each year between 2020 and 2030 if we stand a chance of keeping global temperatures to within 1.5C. This is a long way off current performance which saw emissions increase by 1.7% in 2018 and 0.6% in 2019.

The impact of the pandemic is expected to make a serious dent on this year’s total, with the International Energy Agency (IEA) predicting a decline in CO2 by up to 8%, the largest ever recorded. But as the IEA pointed out, this is “nothing to cheer about”. It has taken a deadly, global virus to cut emissions to the extent we need and will continue to need for the next nine years.

The upside is that emissions are declining at a greater pace than during the last global crisis. In 2008, the Great Recession resulted in a doubling down on fossil fuels as national governments sought to kickstart their economies by any, and all, means necessary. Today, things are different. European nations have strongly supported a green recovery with the European Union committing a €750 billion stimulus package which prioritises green projects across the board. And 30% of the next EU budget will be spent on fighting climate change. It’s a start.

The UK is also stepping up with emerging plans to create a truly green economy and a new 2030 target to cut emissions by 68% on 1990 levels. This is an increase from the already challenging 57% target and will mean climate action is frontloaded to the coming decade. The bold new target, if followed through, will mean big, important changes to British society. It will also set the bar high for next year’s UN climate talks, to be hosted in Glasgow, and a clear opportunity for the UK government to take global leadership on climate change.

The picture outside of Europe looks promising too. New commitments on net-zero have been secured by China, Japan and South Korea, with China’s goal to reach ‘peak emissions’ within the next 10 years. And to much relief, the United States is set to come in from the climate wilderness. Joe Biden’s election victory could not be more significant for the world’s environmental prospects. The day after the presidential election, the US officially left the Paris climate agreement. On the same day, President-elect Biden responded that “in exactly 77 days, a Biden Administration will rejoin it.”

Targets and positive statements are one thing, but what’s really needed is a suite of detailed and consistent policies to light the way. Governments have a unique role in setting the course of direction for businesses and consumers. The challenge has always been how big issues such as climate change can be tackled during an administration which might only last four or five years.

To transform our highly sophisticated economies away from high carbon within a generation will require an international effort. To give ourselves a fighting chance, I believe we need to address four key areas where we could be making real progress right now.

Fast-track green research and innovation

We already spend huge sums investing in high-carbon industries, such as aviation and automobiles. By and large these investments are going into maintaining the grip of fossil fuels and not to their zero-carbon alternatives. A post-Covid world needs to prioritise research spending into green technologies of the future. On average, OECD countries spend 2.4% of their GDP on R&D. Plenty of nations fall below this number, with little investment into clean energy innovation.

This needs to change with higher, targeted investments more akin to tech-orientated nations such as Israel or South Korea which spend closer to 5% of their GDP on innovation. Furthermore, energy start-ups need access to the wealth of capital and expertise already commanded by industry insiders. This will support new ideas and technological improvements.

Better regulation

The UK energy market has gone through different stages of liberalization and regulation and is seen by some as one of the more innovative regulatory frameworks in the world. However, the downside is 10,500 pages of rules reflecting different policy priorities, many of which do not support our goal of a zero-carbon marketplace.

Regulation ultimately guides what businesses can and cannot do in this space. The wrong kind of regulation can seriously impact the direction of travel. And national regulators which do not have a mandate on decarbonisation will be holding back progress. So, we need to take a step back and ask a difficult question: how can we create market mechanisms designed to shift the whole system towards net-zero?

Stronger Infrastructure

Our energy grids were designed to serve high-carbon, centralised technologies, such as big coal or gas plants. Over 85% of British homes are connected to the gas grid. This must change and we need a radical rethink of how energy infrastructure can be built and adapt with clean tech in mind.

Energy networks are often old, inefficient and favour the large incumbents. A zero-carbon grid can’t survive on such an outdated model.

Instead, the grid needs to accommodate different technologies where consumers play an active role. In Europe, over 500,000 battery electric cars have been sold in 2020 alone. The UK government is targeting the sale of 600,000 heat pumps a year by 2028. This is a new world where EVs charge at home overnight, joined by renewable technologies generating at different times of the day, backed up by battery systems storing excess energy. Powering the cities of the future will feel very different.

Empower consumers

Our efforts to cut carbon emissions have so far been achieved without changing the average household’s behaviour. The next stages of our net-zero journey will need to have consumers at the centre. The UK’s Committee on Climate Change has pointed out that over 60% of the measures to reach net-zero will require societal or behavioural changes. This step change will require high levels of engagement in the way we use and consume energy.

Our homes will need to become mini power plants, enabled by smart technologies which know when to use clean power, store it, or send back to the grid. We first need to fully understand what consumers want and then design clean products which can compete with their highcarbon rivals.

Polling from the United States is informative. Some 73 per cent of household respondents to one Deloitte survey cited cost savings for wanting to buy clean tech services, but 43 per cent were concerned about security. The consumer transition needs to be achieved in an open and transparent way which builds trust.

This plan is a snapshot of what needs to change, but focussing on these four pillars will go a long way to securing a green recovery and solving the net-zero puzzle. The pandemic has given us an opportunity to invest in this new world. A world where for the first time we can improve quality of life without destroying the environment.

Juliet Davenport is Chief Executive of Good Energy which she founded in 1999. She also sits on the boards of The Crown Estate, Renewable Energy Association and Innovate UK, and is Vice President of the Energy Institute.