Winter 2016

Latin America and the Decline of the Caudillo

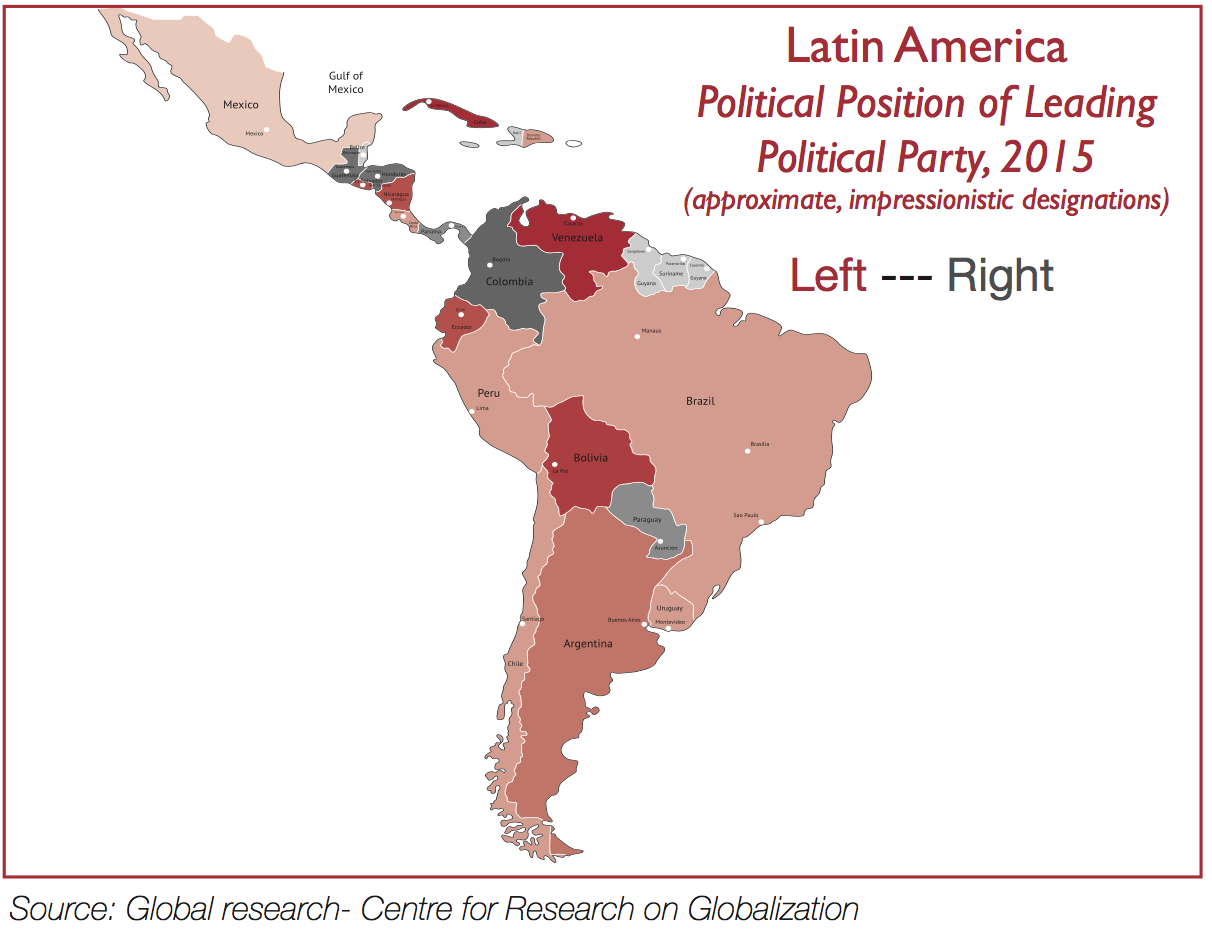

While populism is on the rise in parts of Europe, Asia and Africa – and now in the United States with President-elect Trump’s victory – most Latin American countries are experiencing major political transitions as the wave of populism that engulfed the region for more than a decade is moving in an opposite direction and rapidly receding. Dissatisfied with the economic consequences of different heterodoxal policy experiments, voters across the region are pushing the political pendulum back from the left and toward the centre. But the extent and duration of this incipient political change is still uncertain.

Its fate will largely depend on the political authorities’ ability to rapidly attain macroeconomic stabilisation and rebuild damaged institutions. Mexico, Colombia and Chile are today exceptions to this trend because populism never really took hold in these countries and their economies performed well in comparison with others. In the case of Mexico an additional reason has been that the country has had a democratic political transition process with no recent history of military takeovers or dictatorial governments.

Source: Global research- Centre for Research on Globalization

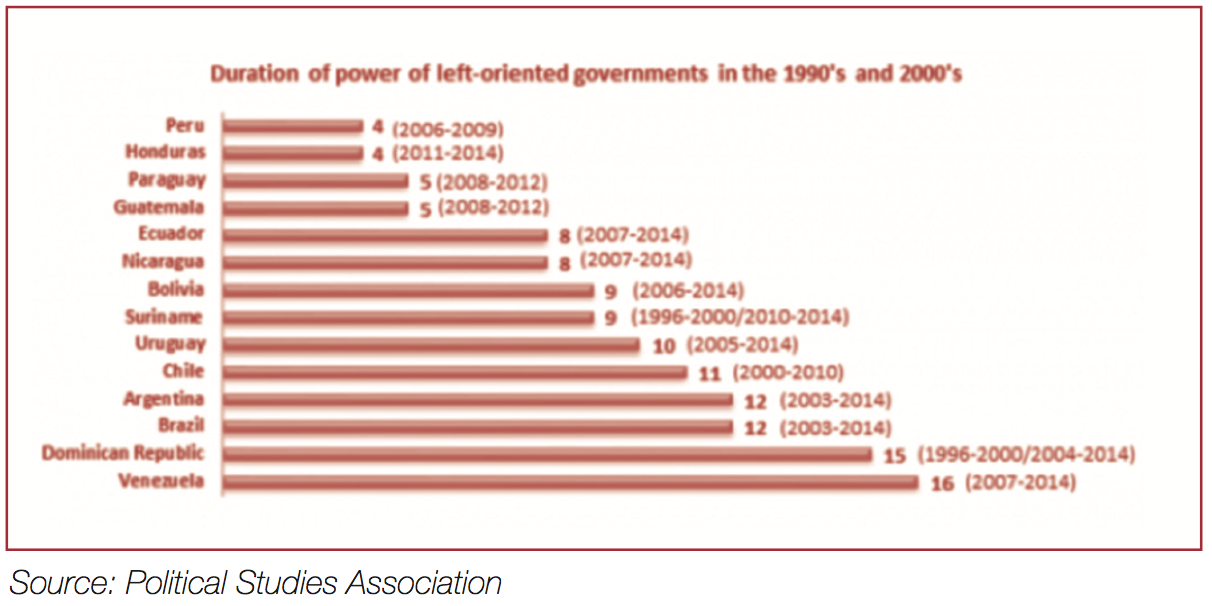

The turn of the century marked the ascent of left-wing parties across many parts of Latin America. From Caracas to Buenos Aires, voters favoured different shades of populism or leftist administrations. Hugo Chavez in Venezuela (1999), and to a lesser extent Evo Morales in Bolivia (2006) and Rafael Correa in Ecuador (2007), embraced the most radical version of neo-populism. Following a severe economic crisis in Argentina, Nestor Kirchner (2003) resuscitated many of the guiding principles of the old Peronist form of populism under a new label of Progressivism, followed by his wife Cristina and the implantation of Kirchnerismo from 2003 to 2015. Other left-leaning presidents, like Lula Da Silva in Brazil (2002), Tabaré Vazquez in Uruguay (2005), or Ollanta Humala in Peru (2011), adopted more moderate stances, but still represented the populist strain of politics in the region. Finally, we have the extreme example in Nicaragua of a populist leader who has just been re-elected – together with his wife as Vice President – with a sweeping 75% majority for the third time since 1984.

But regardless of the discernible differences between these leaders, their arrival to power can be traced back to a sense – right or wrong – that the policies broadly identified with the Washington consensus of the 1990s were behind the economic and social deterioration spreading across the region. Not surprisingly, breaking with the status quo meant appealing to the disaffected majority of the population, not unlike the phenomenon which we witnessed in the Presidential campaign of the United States – with Donald Trump as the epitome of a populist candidate appealing to the economically depressed sectors of Americans fed up with stagnant wages, high unemployment and a perception that Washington and politicians are to blame for all their problems.

The populist framework in the first decade and a half of the century was validated by economic growth, driven by expansive economic policies that were mainly financed by high commodity prices. Re-elections were secured amid elevated consumption, low unemployment and growing social benefits on the back of current account surpluses and ample availability of external funds. Cristina Kirchner (2007) in Argentina, José Mujica (2010) in Uruguay, Dilma Rousseff (2011) in Brazil, and Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela (2013) took over from their predecessors and, in some cases, intensified the populist agenda.

Source: Political Studies Association

Populism seemed inexorable and poised to endure in a region accustomed to strong leadership and affected by large pockets of poverty. But the unsustainability of its typically inconsistent and heterodox economic policy mix ended up planting the seeds of its own demise. In fact, this recent cycle of populism followed a similar pattern already exhibited in past cycles as typified by Dornbush and Edwards (1990)[i]. They identified four phases of economies managed by populist administrations. A first phase of economic expansion, usually followed by a second phase of nascent shortages and growing macroeconomic imbalances, and then by a third phase of political instability stemming from unsustainable macroeconomic dynamics. The final phase usually consists of the politically unpalatable implementation of a macroeconomic stabilisation programme with recourse to external financial institutions like the International Monetary Fund.

This cycle is evidently coming to exhaustion in many countries of the region. The end of the commodities boom and related economic deceleration of China have only accelerated its inevitable decline. In Argentina, businessman Mauricio Macri (2015) rose to the presidency amidst severe stagflation and a population tired of the excesses of the Kirchners and Peronism. Center-right candidate Pedro Pablo Kuczynski surprisingly won the presidential elections in Perú as someone perceived to have economic and financial experience. In Venezuela, where populism runs deeper and has captivated the least well-off of the population, President Maduro constantly faces the prospect of a recall referendum on the back of a critical economic downturn, the precipitous drop in oil prices and disastrous shortages of food and medicine. And while populism still appears to have some support in Brazil, President Rousseff saw her approval ratings plummet amid a severe recession and high inflation, and was eventually impeached. Her successor immediately began to unwind many of the populist measures that initially gave her and Lula Da Silva the backing of the majority of Brazilians. Finally, with the demise of Fidel Castro in Cuba a powerful symbol of populist dictatorship has gone, even though the régime under his brother continues on the autocratic, undemocratic path begun almost 60 years ago.

While the political transition toward the centre brightens the region’s medium-term prospects, it increases uncertainty. New administrations face the difficult challenge of implementing painful economic corrections while trying to work with a relatively weak political base and opposition by some of the more traditional legislative groups and party officials. With the spectre of populism never far away, they are being pressed to deliver short-term economic results to keep the pendulum from swinging to the left yet again, a task made more difficult by the slowdown in the global economy. The case of Argentina, where the transition started some months ago, illustrates these challenges. Macri’s administration has already implemented important policy corrections, including the removal of exchange rate restrictions, the solution of a lingering external debt default, and some rationalization of monetary policy. Nonetheless, it has shown less conviction in advancing with a politically unpalatable reduction of the country’s sizable fiscal deficit. Even in Brazil, President Temer’s first decisions to remove some of the more critical obstacles to investment and trade have been heavily criticised by large groups of the population that enjoyed the heavy subsidies and populist programs put in place by Lula Da Silva and Rousseff.

Mexico will again see Andrés Manuel López Obrador as a presidential candidate in 2018. He is the epitome of a populist politician, always ready to appeal to the lower levels of the country’s socio-economic sector, promising the moon and constantly criticising whichever government happens to be in power. A true test of the durability of Mexico’s rejection of populism and success of President Peña Nieto’s structural reforms will come if AMLO once again loses and Mexicans reject his facile siren song.

At this stage it’s difficult to foresee whether other reform-minded leaders will be able to deliver what their peoples demand, and whether their governments will be short-lived or represent a significant change away from the populist policies of their predecessors. Much will depend on the success or failure of their economic policies and on whether they are able to garner the political support needed to push ahead with major macroeconomic reforms as has been the case with Mexico. If they fail the pendulum could easily swing back towards populism and “easy” remedies to deep-seated structural problems.

[i] Dornbush, Rudiger and Sebastian Edwards; “Macroeconomic Populism”, Journal of Development Economics 32 (1990), 247–277, North Holland

Andrés Rozental holds the lifetime rank of Eminent Ambassador of Mexico. He occupied a number of senior positions in his counter’s foreign ministry including Deputy Foreign Minister, Ambassador to the United Kingdom, Sweden, and Permanent Representative to the United Nations in Geneva. He has held non-executive and advisory Board appointments with numerous multinational corporations, including ArcelorMittal and Ocean Wilson Holdings. He is also Senior Policy Advisor at Chatham House.