Winter 2016

Donald Trump: The Hat Versus the Data

The 2016 presidential election will surely go down in U.S. history as the nation’s strangest and most complicated. This took place under the varying influences of a shifting media landscape, changing demographic trends, and massive technological and economic disruptions – as well as latent sexism and xenophobia, an unprecedented intelligence operation conducted by the highest levels of the Russian government, and a nation hungover from 15 years of fighting losing wars. Unpacking all of this – amid seemingly spiraling global chaos – makes correctly apportioning Donald Trump’s success and Hillary Clinton’s failures nearly impossible. Perhaps the one sure ingredient of Trump’s Election Day shock was that he understood the mood of the nation better than anyone.

Undoubtedly, the politics of 2016 were driven by anti-elite populism. But 2016 was also undoubtedly won by Donald Trump’s fiery and unconventional campaign – a revolution in campaigning that captured a specific moment in time in the same way that John F. Kennedy exploited the new era of television in 1960.

Trump, trained in reality TV entertainment and masterful on Twitter, understood the media landscape in a visceral way that few politicians ever have. From the first day when he rode his golden escalator down from Trump Tower to announce his candidacy, proclaiming the need to protect American from Mexican “rapists,” he understood one of the old dictums of warfare: he who chooses the terrain wins the battle. The US military trains officers to shorten their decision-making cycle using a tool known as the “OODA loop,” an acronym for “observe, orient, decide, and act.” The military believes that the adversary with the shorter, faster OODA loop will prevail. Over the months following his announcement, Donald Trump managed to get inside the OODA loop of all of his opponents. He acted in a manner more quick and agile than any other campaign, defining on his own terms the landscape where the campaign would be won and lost. His daily flurry of tweets, wild pronouncements, and half-truths overwhelmed campaign opponents and journalists alike, leaving them dazed and unsure what and where to fire back.

During the first year of his campaign, Donald Trump’s norm-shattering approach to the media – calling in to TV shows by phone rather than appearing in person, berating news reporters by name at rallies for overlooking stories – allowed him to participate in the news cycle minute-by-minute at times that Clinton’s less press-friendly campaign remained silent. But the effect was so captivating – the political equivalent of a constantly careening train, ready to tip over spectacularly at any moment – that the media kept its klieg lights focused on the ratings-friendly Trump to the exclusion of nearly all other substance. At one low point for the news media, cable news channels showed an empty podium, awaiting a Trump speech, rather than Hillary Clinton’s simultaneous speech to a Las Vegas labor union.

His mix of wacky logic, outright falsehoods, and hyperbole-filled flights of fancy – with policy positions enumerated, edited, and withdrawn seemingly without thought – was rooted in his business background of real estate, where every building and property is simultaneously the “best,” the “greatest,” the “biggest,” and the “most luxurious.” As journalist Salena Zito explained after covering one of his rallies in Pittsburgh: “The press takes him literally, but not seriously; his supporters take him seriously, but not literally.” He capitalized on a unique moment in media consumption, when all news has been leveled into social media feeds, when Facebook and Twitter present headlines from the New York Times with the same weight and prominence as any random blog post spouting unverifiable theories, exaggerations, or outright lies. There was, Trump realized, no real core truth in 2016 — nor, in the public’s eye, any cost to being caught in misleading statements.

In his seriousness-but-not-literalness, Trump also appeared to realize that the nation, tired of political gridlock, was happy to substitute entertainment for the drivel of policy. Whereas Clinton’s campaign churned out careful policy paper after thoughtful treatise, Trump managed to finish the campaign without truly enumerating a single thing he would reliably do – even backing away at times from the literalness of building a wall along the border with Mexico. Instead, Trump exploited every moment of the attention on him, treating the national press corps like a rolling informercial and reality show, dragging reporters on tours of his own branded properties, advertising the supposed success of even failed products like Trump Steaks, and, after winning the White House, referring to potential Cabinet picks as “finalists.”

In a 24-hour news environment, he was the first candidate to provide 24 hours of news. In Neil Postman’s 1985 book, “Amusing Ourselves To Death,” the New York University professor warned that the nation seemed well on its way to realizing the disturbing vision of Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World,” a materialistic and docile citizenry conditioned to treat everything as entertainment. “Entertainment is the supra-ideology of all discourse on television,” Postman wrote. “Everything about a news show tells us this—the good looks and amiability of the cast, their pleasant banter, the exciting music that opens and closes the show, the vivid film footage, the attractive commercials—all these and more suggest that what we have just seen is no cause for weeping.”

At its core, though, through all of the daily changes, zigs, and zags, Trump’s message was as simple as it could be – a clearly articulated goal and message to those feeling left behind. As one focus group member said in 2015, “We know his goal is to Make America Great Again,” a woman said. “It’s on his hat.” Meanwhile, his message contrasted with Clinton’s more muted “Stronger Together,” a message focused on unity and diversity that offered little in the way of appeal to the economically disenfranchised.

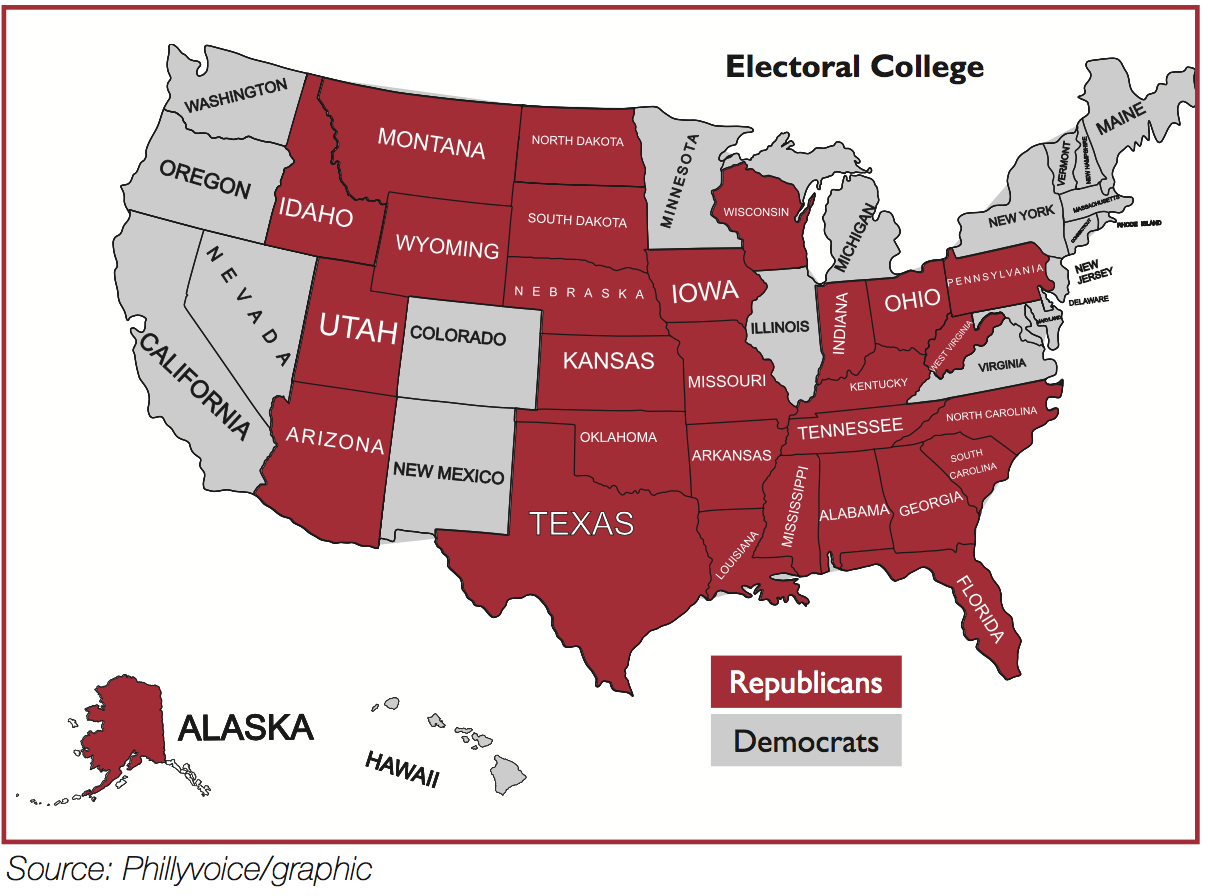

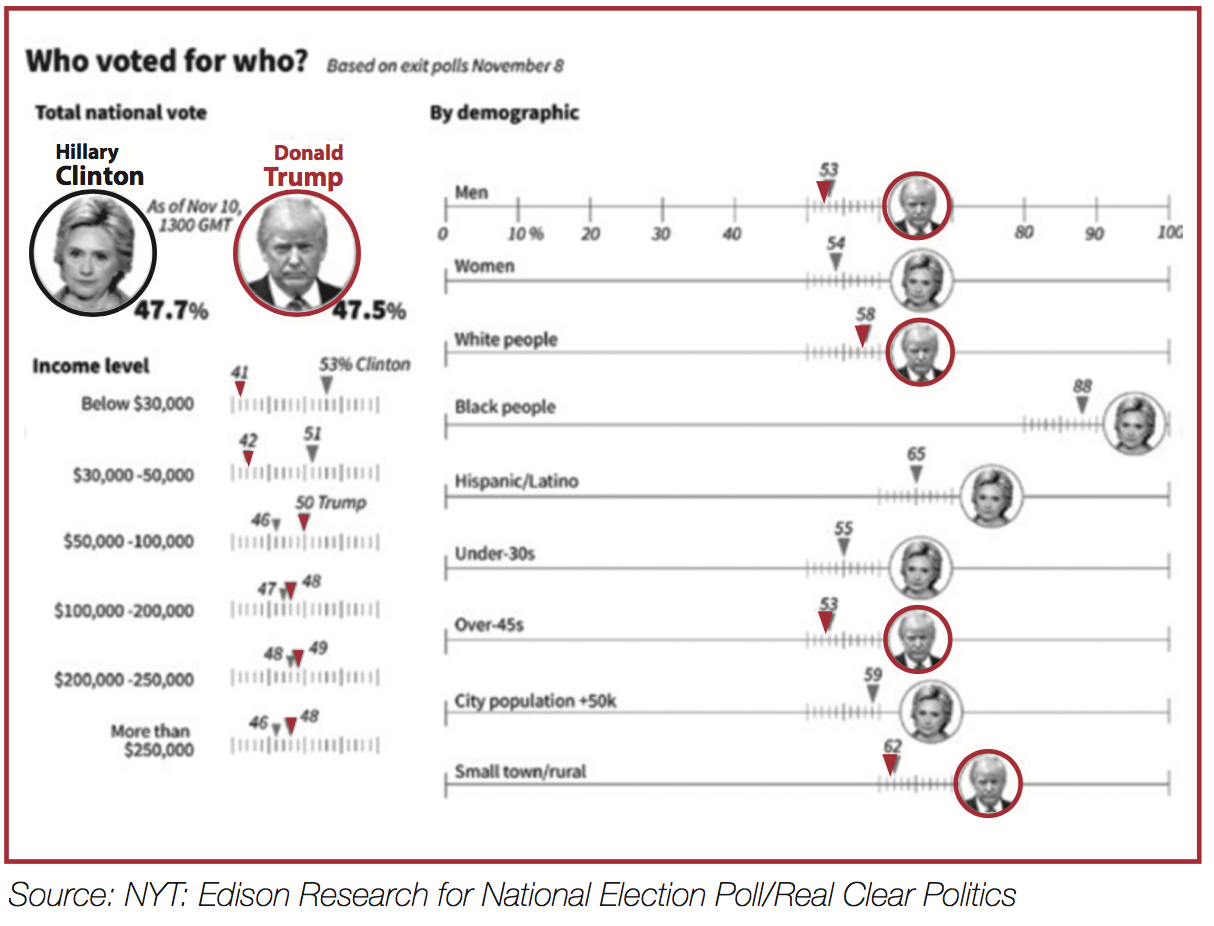

The anxiety that drove Trump’s campaign actually came from wealthier populations with a low education – not the poorest Americans, but those who a generation ago could have counted on a solid manufacturing job to secure their families in the middle class. He capitalized upon the hollowing out of America’s vast interior, as wealth and jobs cluster into intellectual and financial centers like university towns and major industry hubs – finance in New York and Chicago, biotech in Boston, startups in San Francisco. Trump won – overwhelmingly in the end, rural regions, attracting many of the same voters who supported Obama eight years ago. He also overwhelmingly won older Americans who feel left-behind by the changing economy and cast aside in a diversifying world. One poll found that 8 in 10 Republican voters feel like they’re feeling on the “losing side” of the nation’s political debates.

The rural-urban split helps to explain one of the oddities of the election results: despite Donald Trump’s year-long campaign of hate, doom, and gloom, the United States is paradoxically, by most objective measures, in solid economic shape. It continues the longest uninterrupted economic expansion in a century (albeit a slow one), the stock market has soared, unemployment has dropped by half, as has the nation’s rate of those without health insurance. Yet those benefits have been shared unequally around the country, with most of the benefits accruing to the well-educated urban elite; incomes have risen dramatically for those at the top and stagnated or even dropped for the bottom two-thirds of the country.

Such underlying inequities and rising inequality make clear that Trump shouldn’t be dismissed as an orange-maned one-off aberration. While the global elite hope to write-off Trump as sui generis, a historical accident, his success was hardly an outlier in 2016: in fact, three of the four final candidates in the U.S. presidential race – Trump, Ted Cruz, and Bernie Sanders – each represented an anti-establishment voice, one with barely if any ties to the party elite. All three had few friends inside Washington and few of the establishment’s top strategists, pollsters, or staffers working on their payrolls. Two of those final four, Trump and Sanders, hadn’t even been members of their respective political parties until setting out on the campaign trail. All three stood for a clear rejection of the globalist free-trade agenda that has dominated both parties for a generation, creating the odd dynamic where Hillary Clinton and Jeb Bush had more of a worldview in common than either did with Sanders or Trump. This elite vs. the anti-elite split helps explain how Trump chugged victoriously through the spring primaries while never winning much more than a small plurality.

As Trump’s unconventional run focused on the gut anxiety of the shrinking population of white middle-class voters, the fourth candidate in that mix – the glass-ceiling-shattering former First Lady who became the woman to ever earn a major party’s presidential nomination –concentrated on running a seemingly conventional campaign, a low-drama, data-focused, technocratic and press-wary operation. Clinton’s campaign focused an agenda around the working poor – paid family leave, free community college, and a higher minimum wage — rather than the middle-class. It was an agenda for those striving to achieve the American dream, rather than those who have achieved it and now fear the American dream slipping away. Yet even Obamacare failed to connect with Trump’s audience, for while the Affordable Care Act has been a tremendous success for the working poor, it’s turned into a spiraling disaster for those families who make too much to receive the tax subsidies.

Trump followed none of Clinton’s playbook, reshuffling his campaign staff regularly and eschewing nearly all of the traditional trappings of a campaign ‑opening few field offices, advertising little on television beyond his high-wattage rallies, and spent little time formulating any policies; many of his Washington-based policy team drifted away as the campaign unfolded after being sidelined and left unpaid. He felt, correctly as it turned out, that large free-wheeling and boisterous rallies could replace all the careful logic of a normal campaign “ground game.”

At every level, Trump versus Clinton was enthusiasm versus organization.

In many ways, Trump’s election was the second major campaign revolution in just a decade. Until 2008, presidential campaigns had looked largely the same since the 1970s, when caucuses and primaries came to the fore, and still bore a substantial resemblance to the way campaigns had been fought since the ’50s and ’60s when television advertising launched a seemingly ever-escalating air war.

Source: NYT, Edison Research for National Election Poll/Real Clear Politics

Barack Obama understood how to harness a changing nation and advancing technology better than anyone else in 2008 – delivering a sweeping victory that mixed soaring speeches with critical get-out-the-vote outreach via cell phone text messaging. By the end of the campaign, Obama – flush with money from small-dollar fundraising online—was even buying advertising inside Xbox video games, precisely targeting the voters he needed to turnout. It was a campaign seemingly unlike any other in American presidential history: Obama, a tech-savvy African-American first-term US Senator only a few years removed from the Illinois legislature, likely could have never won an election before 2008. Yet he navigated to victory perfectly the nation’s shifting media preferences and changing demographics. Similarly, Donald Trump’s unique approach and mix of tactics likely never could won a campaign before 2016 – and, thanks to the aging Baby Boomers and the rising millennials, will struggle to ever reassemble the same coalition to win a future presidential election.

In that point lies part of the challenge for both the Republicans and the Democrats: it’s easy to make too much of Trump’s victory. In effect, Trump was elected with the active support of fewer than one in five Americans. Republicans lost the popular vote for president for the sixth time in the last seven presidential elections, overall turnout was down dramatically from 2008 and 2012, and Trump won a smaller percentage of the vote than Mitt Romney did in 2012. The coalition of African-Americans, Hispanics, Asians, millennials, and college-educated white women who supported Clinton, and rejected Trump by huge margins, will represent an ever-larger portion of the US electorate in future years, and the Baby Boomers’ influence will shrink every year.

Trump’s victory in 2016 was more of a tactical victory than a strategic one – even his own pollsters and advisors were surprised when he won. And the unique media environment, where Trump himself, working his own Twitter account, owned the nation’s largest megaphone, was able to win the presidency sans infrastructure, ensuring his victory is a lonely one. He won with none of the sophisticated staffing and policy apparatus that a presidential campaign normally entails, and now faces the daunting task of running a massive government, a massive economy, and a massive military with no experience in public service, elected office, and, overall, a shockingly poor record in business.

There’s little evidence from his chaotic, infighting-filled transition, game show-style Cabinet interviews, and undiplomatic and sour grape-themed tweets as President-Elect, that would indicate he appreciates the gravity of the governing process ahead.

That reality likely will mean his voters will be disappointed, as it’s hard to see how and where a Trump presidency might actually begin to return America to the broad rising economic and middle-class tranquillity of the 1950s and 1960s. Generational shifts means the country will continue to grow more diverse, even if immigration is brought to a complete halt. And it is merely a quirk of history that globalization shifted manufacturing jobs overseas before automation destroyed them anyway. As rising costs in Asia and Mexico push manufacturers to return to the United States, factories are returning with just 20 jobs where they might have once boasted 200. Many of the trends encouraging urbanization will continue regardless, as will the trend towards higher-skilled jobs. The Rust Belt’s one-time steelworkers are not just one or two Javascript coding classes away from being hired onto Facebook or the next hot Silicon Valley startup.

Trump’s victory, however unconventional yet perfect for the moment, forces an uncomfortable question upon the world: how does one lead — or even communicate – now that it’s clear that the general public doesn’t particularly care about the truth? Throughout his 18-month insult-laden campaign, Donald Trump proved to the world that all of the norms of civilized society are breakable, seemingly with little cost. With such a shift in society’s Overton Window, the window of discourse that people will accept, Trump has exposed that modern democracy is far more fragile than anyone imagined.

Indeed, perhaps the scariest take-away from 2016 should be that as a world, we’re only just beginning to feel the effects of massive economic, technological, and climatological change. As much as his victory marked perhaps the last gasp of a dying generation of American white voters, President Donald J. Trump might very well merely mark the beginning of the upheaval ahead.

Garrett Graff is an American journalist and historian, writes for Wired and Bloomberg Businessweek, among other magazines, and formerly served as an editor of POLITICO Magazine. His next book, Raven Rock, about the U.S. government’s Cold War doomsday plans, will be published in 2017.