Winter 2016

Immigration, Brexit and the Cultural Difference

The Brexit vote was evidently not just about immigration. But if there is a paramount reason for Britain’s shock decision to leave the EU it is the seething discontent of a large slice of public opinion created by 20 years of historically unprecedented immigration and the insouciant response of most of the political class to this change – a change that never appeared in an election manifesto and was never chosen by anyone.

The consensus of establishment opinion over the past generation – minus several influential tabloid newspapers – has ranged from a happy embrace of the cultural and economic benefits to a belief that it is an uncontrollable force of nature. Yet around 75 per cent of the population (including more than half of ethnic minority citizens) has consistently told pollsters that immigration is either too high or much too high, with the salience of the issue rising steadily to the top, or near the top, of the list of national concerns in recent years.

It is true that people are swayed by sometimes alarmist media reporting and are often ignorant of the facts of current immigration but it is also the case that increasing anxiety about immigration since 2000 has very closely tracked increases in the actual numbers. (Those numbers are now about 600,000-plus annual gross inflow – 330,000 net – of people coming for more than a year. About half is work related and the rest, in order of size, is students, family reunion and refugees. Only about one third of that net inflow currently involves permanent settlement.)

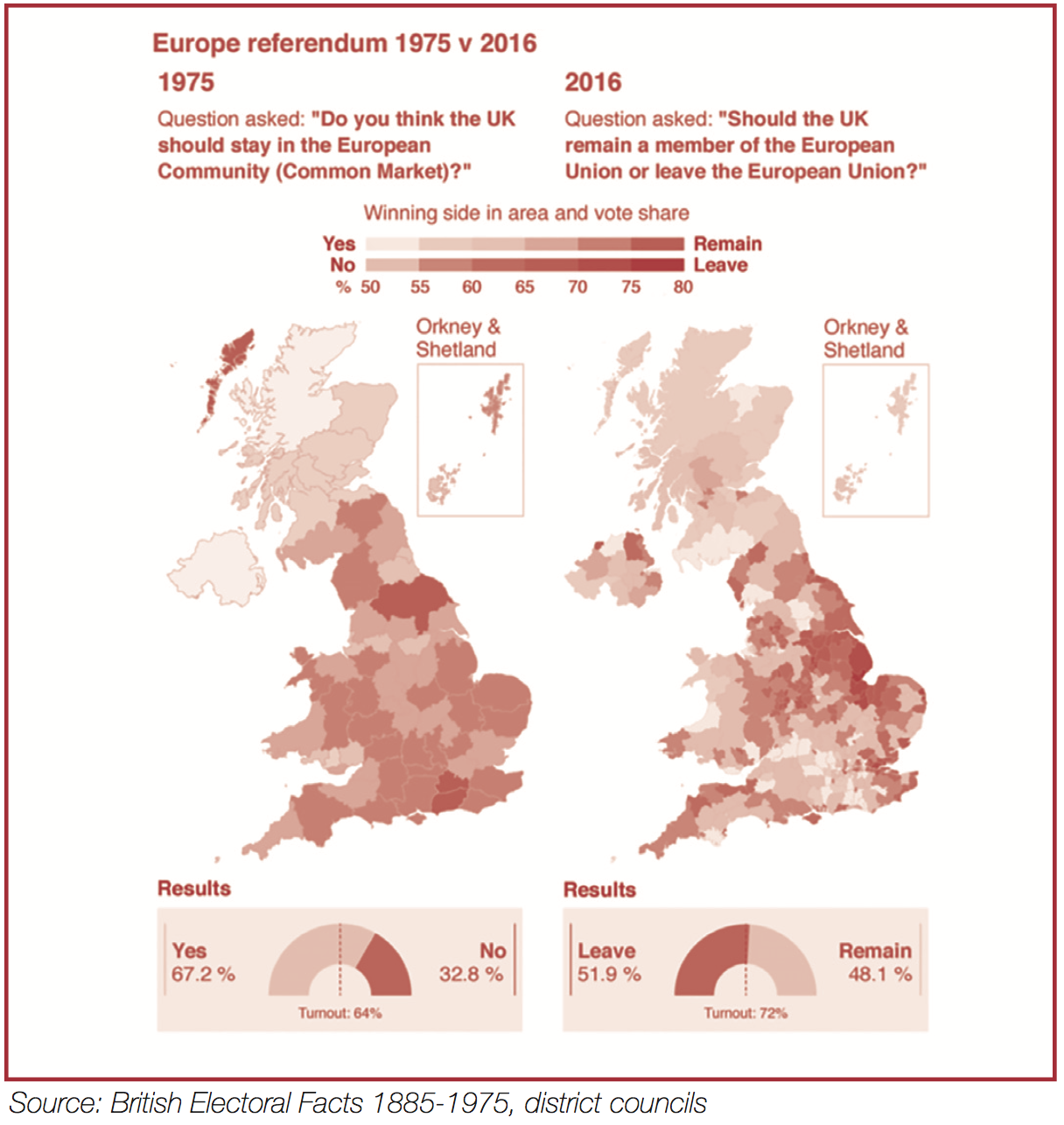

Source: British Electoral Facts 1885-1975, district councils

Of course, immigration has become a metaphor for the larger disruptions of social and economic change, especially for those who have done least well out of them. In the quiet of their living rooms most people have quite nuanced views on the value to the country of different types of immigrant, and tend to be more positive about the local story, yet immigration overall still stands for “change as loss.”

This should be no surprise. It is a basic human instinct to be wary of strangers and outsiders. In rich, individualistic modern societies, tribal and ethnic instincts may have abated but they have not disappeared completely and have been supplemented by anxiety about sharing economic space and public goods with outsiders.

But Britain has not become a country of angry nativists and xenophobes. Indeed, one of the remarkable things about the growing opposition to immigration in recent years is that it has been accompanied by increasing liberalism on almost all cultural matters, including race.

But this requires several caveats. First, there is a core of hard authoritarians and bigots, maybe 5 to 7 per cent of the population. The BNP won nearly 1m votes in the 2009 European elections.

Second, there is a much larger group who broadly accept the shallow liberalism that is the dominant ethos of modern Britain and are comfortable with difference at a micro-level at work or in social life, yet still do not like the macro changes to their city or country as a whole and worry that too many newcomers are not integrating into British life. They are not hostile to newcomers or people from different backgrounds but do not want to lose a sense of ownership of their area, a sense that people like them set the tone in the kind of shops and the way of life.

Third, although chauvinistic nationalism is much rarer in modern Britain than it was a couple of generations ago, attachment to national social contracts and the common sense belief that national citizens should be first in the queue remains as strong as ever. This does not necessarily make you a flag-waving nationalist but it might make you more sensitive to competition with people you see as outsiders for school places or hospital beds or social housing.

The 2016 BSA survey finds that 71 per cent of people think immigration increases pressure on schools and 63 per cent say it increases pressure on the NHS. The same survey finds that 42 per cent think that immigration is good for the economy with 35 per cent saying it is bad. But there is a sharp class division: just 15 per cent of graduates think immigration is bad for the economy compared with 51 per cent of those with no educational qualifications.

Is this false consciousness? To many liberals the popular hostility to large scale immigration is a classic example of people sacrificing their material interests to their cultural values.

That assumes a significant and widely spread economic benefit from current immigration. It is true that the effect on jobs and wages, even at the bottom end, is less negative than often assumed – and employment rates are at an all time high for the British born. But mass immigration is still somewhat regressive (and would have been more so in recent years without the minimum wage) and there is not a strikingly positive economic story for the existing population on wages, employment or growth per capita either. Taking immigration as a whole in recent decades the fiscal contribution of newcomers is slightly negative though for Europeans alone it is probably slightly positive.

It is a different story for employers who have been able to sharply cut their training bills in recent years and replace the sulky, poorly educated local teenager with, say, a keen-as-mustard Latvian graduate who speaks excellent English. The public sector too has been able to cut, for example, nurse training budgets and recruit already trained nurses from Portugal or Poland.

It is often observed that it is areas of lowest immigration that are most opposed to it. That is only partly true as it seems (according to an Economist analysis) that it was places that had seen the highest rate of increase of immigration that were the places most likely to vote Brexit; in Boston, Lincolnshire, for example or Stoke where the foreign born population increased 200 per cent between 2001 and 2014. But, in any case, that misreads the social psychology of mass immigration. Xenophobia exists but more important is the psychology of recognition, or rather the lack of it. Areas of low immigration are often depressed former industrial areas or seaside towns where people feel that the national story has passed them by, as it has. Opposition to immigration there is not so much about blaming immigrants as the changing priorities of the country and its governing classes, priorities that no longer seem to include them.

How then with no strong economic rationale and the opposition of a clear majority of the country did we become a country of mass immigration in the last 20 years?

Having absorbed, not without friction, the post-colonial wave in the decades after the 1950s Britain in the mid-1990s had become a multiracial society with an immigrant and settled minority population of around 4m, about 7 per cent.

It was not at that stage a mass immigration society with persistently large inflows. Today it is. About 17 per cent of today’s working age population were born abroad and in the past generation Britain’s immigrant and minority population (including the white non-British) has trebled to about 12m, or over 20 per cent (25 per cent in England).

Some of this is an open society success story, consider the increasingly successful minority middle class. But to many people the change is simply too rapid, symbolized by the fact that many of our largest towns, including London, Birmingham and Manchester – where more than half the minority population live – are now at or close to majority-minority status.

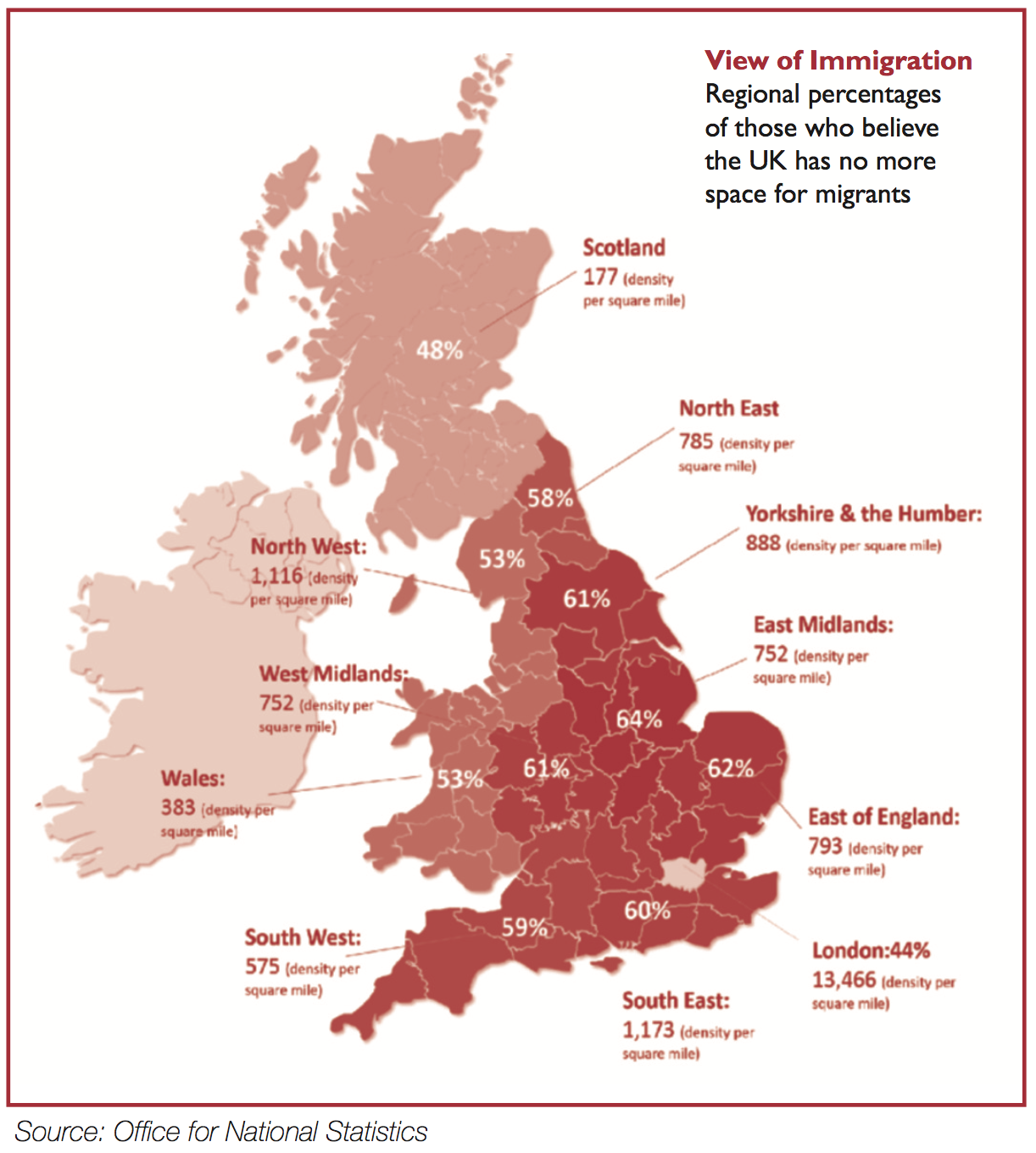

Source: Office for National Statistics

Up until the mid 1990s Britain had never had gross annual inflows of over 300,000 since the mid-2000s the annual inflows have never been below 500,000. This step change is not unique to Britain and is part of what we call globalization. But it was not inevitable on that scale and required the active political support of the 1997–2010 Labour governments.

Labour did not intend to turn Britain into a mass immigration society but most party leaders and activists, increasingly drawn from the liberal graduate class, felt at ease with the change. Indeed, as New Labour increasingly converged on a centre-right consensus on economics, being pro-immigration and pro-multiculturalism loomed ever larger in the centre-left political consciousness.

Several decisions were taken by Labour, all of which were reasonable in their own terms, that together created a far more open immigration régime (underpinned by the new Human Rights Act which made it harder to keep people out or deport them once here).

What were those decisions? There was the repeal of the “primary purpose rule” that had made it tougher for some ethnic minority groups to bring in spouses. The rule was regarded as discriminatory by some South Asian groups and its abolition was a payback to loyal minority voters. Much more important, higher education was just beginning its rapid internationalization, something actively encouraged by Labour as a means of financing a more general expansion of the university sector. With a booming economy and low unemployment there was also pressure from certain business sectors to increase work permit quotas. And when Balkan asylum seeker numbers rose sharply at the end of the 1990s there was an incentive to move people from the asylum route, with all the cost and dependency involved, to the work permit (and tax paying) route.

And then came the big one. In 2004 the former Communist countries of central and eastern Europe joined the EU and Britain was the only big EU country to allow them immediate access to its labour market. It was expected that a few thousand a year would come, in fact more than 1m people came over the next 4 years. There are now 3.3m citizens of other EU countries living in Britain up from less than 1m in the late 1990s and about half of them are from central and eastern Europe.

That 2004 decision is, in retrospect, one of the biggest steps on the road to the Brexit vote. The scale of arrivals was, of course, a surprise and there were economic and geo-political reasons to support the opening. Yet the lack of internal party opposition to the decision was evidence of how removed Labour metropolitans had become from the intuitions of most ordinary people.

Back in the 1970s and 1980s British politicians of left and right moved swiftly to limit Commonwealth immigration in response to democratic pressure from below—by the late 1980s net immigration was almost zero. Forty years later a new generation of politicians, especially on the left, were unable to do the same partly because their progressive politics was bound up with the inflows and, in any case, they had lost the power to control the inflows from the EU which were causing the greatest anxiety.

Labour then lost the 2010 election, with its stance on immigration a decisive factor according to some analysts. The Coalition then took power with a Conservative pledge to sharply cut annual net immigration numbers (from 250,000 to around 100,000).

The Coalition achieved short term success, with Theresa May as Home Secretary reducing net non-EU immigration from 217,000 in December 2010 to 143,000 in December 2013 thanks to clamping down on abuse of student visas, raising the income threshold for people wanting to bring in spouses and effectively banning low-skill immigration from outside the EU.

This dealt with the fallacy that reducing immigration had become impossible in the modern world. But the pledge to reduce net inflows to “tens of thousands” – unwise in retrospect – was badly knocked off course by another surge from Europe starting in 2012, this time mainly young people from Spain, Portugal and Italy escaping the Eurozone crisis. Net immigration was soon back over 300,000 a year.

This is the background to the Brexit vote – one government absent-mindedly ushered in a mass immigration society without asking the voters, the next government promised to rein it in and failed to do so. And that Brexit vote has merely made more complex what was already one of the central tasks of British public policy: how to respond to the legitimate desire of a large majority to reduce immigration while minimizing damage to an economy that has in some sectors become heavily dependent on migrants.

Even when, as part of the Brexit deal, some sort of work-permit control is re-established for EU citizens, Britain’s pull factor of the English language and jobs is likely to remain. For skilled workers there is likely to be a “fast-track” system that will not change things very much. Even unskilled workers from poorer EU countries, or countries further east, will still be needed in some sectors like social care.

British workers are prepared to do tough and anti-social work if it is well paid – look at the oil rigs. But work in those sectors most heavily immigrant dependent – such as agriculture and food processing – tends to be highly seasonal, requiring flexible 24-hour shift patterns, and is often in underpopulated areas of the country. And thanks to the margin pressure from the supermarket chains pay is as basic as the law will allow. This is not work that people with other options will willingly take.

Nonetheless the mass importation of eastern European labour after 2004 was a shock to many British people. This was in-your-face globalization. It is one thing to lose your job because your factory has relocated to a cheaper labour country it is quite another thing to find foreign workers, with little or no historic connection to the country, competing with you in your own country. Food manufacturing, for example, is Britain’s biggest manufacturing sector employing around 400,000 people, and more than one third of production staff are foreign born, mainly from eastern Europe, up from almost zero in 2005.

Britain is likely to remain quite a high immigration country for the foreseeable future although after Brexit the number of low skill workers from the EU will eventually fall. The future direction of policy is likely to involve making a clearer distinction between permanent and short term migrants—more than half of the annual net migration flow into Britain is short term (students or workers) and in recent years only on average about 100,000 people a year were being granted permanent residence.

The lack of a clearer distinction between permanent and temporary citizens creates unnecessary resentment: people see workers from, say, Romania or Bulgaria, enjoying the full benefits of British citizenshp yet unable to speak English properly and living in east European enclaves, apparently treating the country as a temporary economic convenience. But when someone sees a Chinese student they do not think like that. They are more likely to think there is someone who is here for a few years – to the mutual advantage of Britain and the student – who will return home soon.

In the future, temporary citizens should have more limited social and political rights – corresponding to their own transactional relationship with the country – and should leave after a few years. We can then concentrate rights, benefits and integration efforts (such as language tuition) on those who are making a full commitment to the country. There is a trade off, as academics like Martin Ruhs and Branko Milanovic have argued, between migration and citizenship. If we want to continue with relatively high inflows we have to ring-fence the welfare state and full citizenship more jealously.

Britain became a mass immigration society, much as it became an imperial one, in a fit of absence of mind. The political class must now realize that managing that better is at the heart of what a modern state offers.

David Goodhart is Head of Demography, Immigration & Integration at Policy Exchange, the leading UK think tank. He is a former Director of Demos, and former Editor of Prospect Magazine, which he founded in 1995, and where he remains Editor-at-Large.