Winter 2016

Digital Revolution: The Challenge to Democracy

Just over two centuries ago men – and I’m afraid they were all men – started to harness steam power to locomotion. The century that followed saw this innovative network technology spread rapidly across the globe. This great feat of engineering meant that, for the first time in human history, people and goods could be moved faster than the speed of a horse.

It is hard to trace precisely just how much railways contributed to the extraordinary industrialisation of the nineteenth century. At the beginning of that century, two thirds or more of the workforce – 90% in the US – was employed in agriculture. By 1850 it was down to around a quarter in Britain: today it is 1.5%. Alongside inventions such as the telegraph, the railways can undoubtedly claim some credit for the consequent growth in prosperity, for labour mobility and workers’ rights, universal franchise, modern concepts of cities, mass tourism, and above all reducing the sense of remoteness in much of human life. Probably, some might say, also the rise of communism and fascism, and two world wars …

The scale and long-term social implications of the railway builders are worth reflecting on now, because something similar is happening. Men and women — this time — are building extraordinary new technological networks, linking services, ideas, people and passions at the speed of light. As ultra high speed and high capacity networks spread, and the content and services they can deliver are increasingly based in the “cloud” (actually a series of very large interlinked datacentres), so making them available at any time and place, we are starting to see new forms of economic activity emerge, and some old forms disappear. As the “railways of the mind” spread, the capacity that such extraordinary connections will bring into being will revolutionise much in the way we live our lives today.

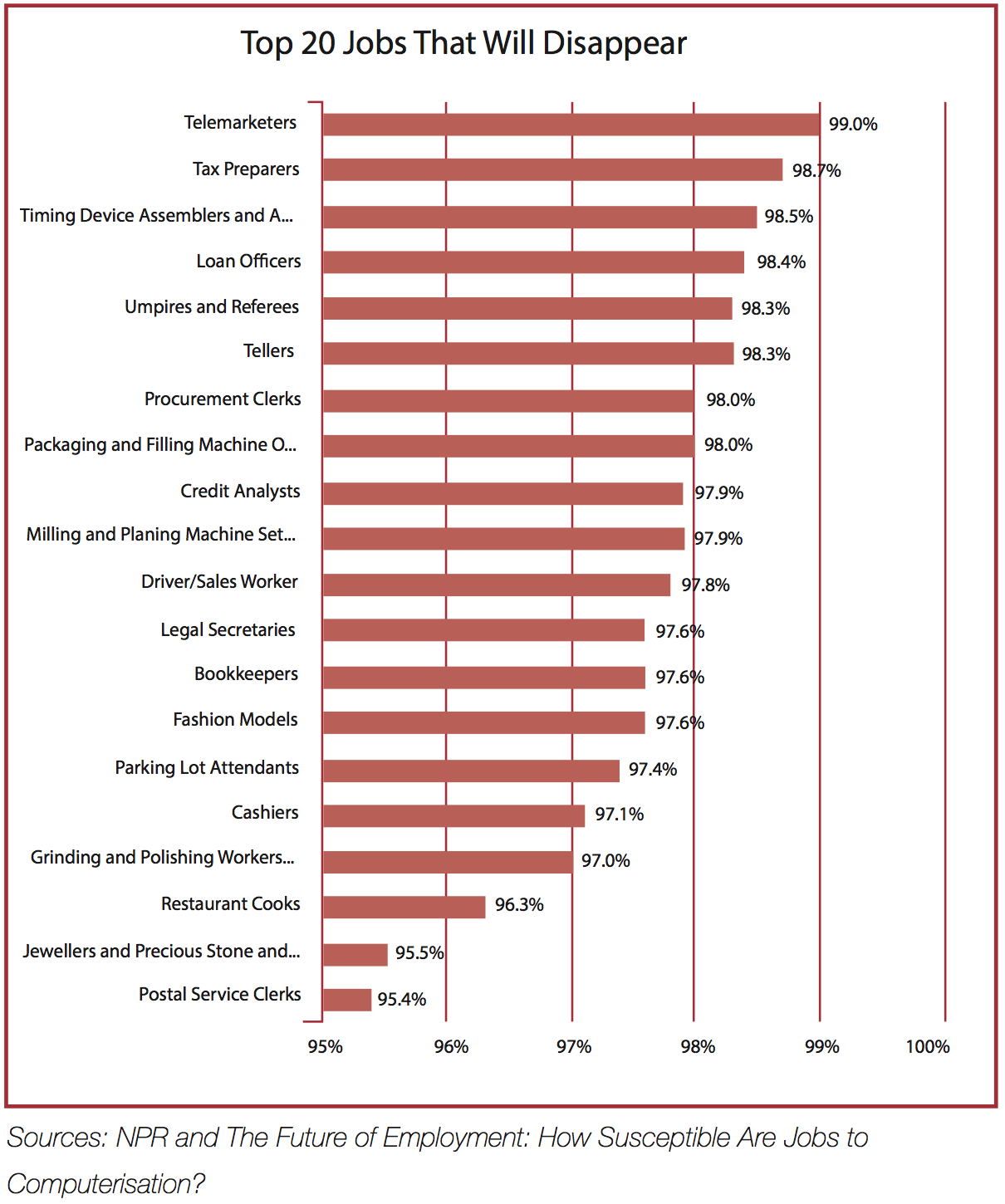

Source: NPR and The Future of Employment, How Susceptible Are Jobs to Computerisation?

What happens to tourism when anyone can set up their spare room as an hotel? What happens to public transport when any vehicle on the road can match spare capacity to demand? What happens to trades unions when industrial processes are mechanised? What happens to traditional concepts of trade when anything can be delivered across the ether at 186,000 miles per second to the 3D printer nearest to wherever you happen to be? What happens to jurisdiction when the originator of an act and its subject can be thousands of miles apart? What happens when artificial intelligence displaces human cognitive reasoning?

I am a profound optimist about the digital revolution. I believe that, like every major technological transformation before it, the new digital world will increase prosperity and accountability, and improve the condition of human life. But the process of getting there is unlikely to be smooth. And it will happen fast – much faster than the century or so which the industrial revolution took to weave the changes it wrought. The change will increase the pressures which are currently driving populist political movements, and at the same time challenge the ability of our existing political structures to address them.What kinds of jobs will there be?

The answer is that – with some obvious exceptions like cyber-security specialists, programme code writers, and privacy lawyers – it is very hard to predict. I believe that the two things which cannot be automated are human emotion and human genius. Emotion and empathy form an essential part of any form of human caring – something most of us do a number of times a day. And I believe that we all have genius within us – not that we could all be Mozart, but that there is some spark of creativity in each of us which could not be replicated by any logic-based programme. The question is how these turn into purposeful and remunerative activities for the majority of the population.

This will in my view be the central public policy question for our time. And yet there is distressingly little sign that governments and policy-makers are starting to address the need to re-purpose much of the workforce in a relatively short time. There will be jobs in the digital future, but will the workers of today have the skills, capability and motivation to do them? And lest anyone comfort themselves by thinking that there are safe places such as the professions, look at what IBM’s Watson super-computer is doing in conjunction with ROSS Intelligence – using cognitive computing and the ability to scan a billion pages of text a second to revolutionise the application of legal knowledge. The risk, if we don’t find a way to show people a positive path through the change that is about to come, is that we will be confronted by a very understandable but ultimate futile attempt to slow or stop the pace of change. I am not sure what is the digital equivalent of the man with the red flag who by law had to walk in front of any locomotive through the second half of the nineteenth century. But we may soon find out unless our politics can find a way to lead us through the change. Can it?

Can representative democracy adapt to the digital age?

In the old days, politics involved parties putting forward a manifesto, a creed, a set of values, an underlying political philosophy. As a citizen, you chose the platform which best suited your views, and packed your representative off to Parliament to legislate in line with the platform. There were two or three such platforms to choose from, so the chances of your feeling the comfort of numbers – knowing that others saw the world the same as you – in your community or place of work were pretty high. That gave people confidence to participate in the choice of platform – political party – without necessarily having to form a view on every issue which confronted the Parliamentarian.

If however you really cared about the preservation of the habitat of, say, a rare butterfly species like the High Brown Fritillary, it could be quite hard to work out which political platform would best serve that interest. And many would be reluctant to raise their voices because of the lack of comfort of numbers – you could go through your entire life without meeting anyone who shared your passion. So your single issue was less likely to distort your general view of politics. Today you can be connected with everyone who shares your concern for a rare butterfly in a matter of seconds. You can instantly enjoy the comfort of numbers, and so feel more empowered to speak up. This is a good thing. But the instant, almost photographic, nature of opinion forming on social networks, sometimes driven by a strong lobby of people with access to mass media whose purpose is to generate “noise” about the issue they seek to promote, can feed into politics as one of a constant and rapid succession of single issues, leaving politicians and their parties gasping to keep up with the latest concern. The platform becomes less and less relevant. But the platform is also the cornerstone of representative democracy. Hence the conundrum for our political leaders as we look to them to guide us through the transformation the digital revolution will bring. The very digital capability whose transformative power so requires confident and forward-looking leadership also challenges, by its disruptive capacity, the basis on which such leadership has been exercised in our Western democracies. Just as industries and professions must adapt to the new digital reality, so must politics and public life.Matthew Kirk is Group External Affairs Director of Vodafone, and a former British diplomat, latterly Ambassador to Helsinki. The views expressed here are solely his, and do not represent those of any organisation.