Winter 2022

Man in the Middle: The Ultimate Disruptor

There is no one like Elon Musk. No one as disruptive, influential or plain rich. The human territory he occupies is entirely his own, far beyond the conventional norms, let alone the even more conventional norms of business. Having founded Tesla and SpaceX, and co-founded PayPal, he already bore comparison to the immortals of American business, the likes of Henry Ford and Howard Hughes, Bill Gates and Steve Jobs.

In an age when great fortunes were attainable by designing software, Musk chose hardware. And not just phones or tablets, yet more devices to enable yet more digital consumption, but cars and rockets. While the car giants fretted at the prospect of electric vehicles destroying their emission-heavy incumbency, it took Musk to show them what was possible, and then to sprint out into a big, early lead as the world swung behind the need for a transition to clean energy. And he did it building cars that are a pleasure to drive.

While NASA mothballed the Space Shuttle and bemoaned the rising cost of space missions, Musk proved rockets were recyclable and that space was best left to the private sector.

And this was all before his smash and grab on Twitter. First, he wanted it. Then he didn’t. Then finally, he closed the deal in early October, just hours before he was due to be deposed by Twitter’s lawyers. Three weeks later, he showed up to work at Twitter’s headquarters carrying a sink, announcing “let that sink in”.

Source: Twitter@elonmusk

While most other CEOs and companies tiptoe around, terrified of negative publicity, Musk is endlessly churning the water, inviting speculation on his motives and ambitions.

In just the fourth quarter of 2022, he proposed a peace plan for Ukraine, involving ceding territory to Russia, which was derided by President Zelensky. Musk does at least have skin in the game, having deployed and funded vital internet service in Ukraine, delivered via his Starlink satellites.

Back in the US, he inserted himself into the middle of a ferocious political debate on free speech. As a public company, Twitter banned Donald Trump from the platform which had such an important role in propelling him to the White House. Musk has invited him back. Though Trump declined, Republicans praised Musk for welcoming back the right-wing voices banished from Twitter. Along the way, Musk told the Financial Times that he thought Joe Biden was too old to run for a second term as President.

Musk also ripped apart the company for which he had just paid $44 billion. He fired hundreds of Twitter’s employees and similar numbers quit in exhaustion or disgust. Musk wrote a memo to staff which will be the stuff of business school classes for years.

Forgetting all the fashionable blather about employee engagement, worker rights and tiptoeing around the feelings of Gen Z, Musk wrote: “Going forward, to build a breakthrough Twitter 2.0 and succeed in an increasingly competitive world, we will need to be extremely hardcore. This will mean working long hours at high intensity. Only exceptional performance will constitute a passing grade.”

At Tesla, Musk would sleep on the factory floor and work 120-hour weeks to meet production targets. Twitter, he has implied, will require similar levels of commitment. He has already shown he is prepared to risk Twitter’s $5 billion-a-year advertising business, by firing most of its ad sales team and giving corporate ad buyers conniptions over his plans for content. He tried to reassure those buyers by saying Twitter would not become a “free-for-all-hellscape”. But now that image is lodged in their minds. The companies which buy ads on Twitter are increasingly frightened about what kind of content will appear alongside their names.

Musk says he has a plan for Twitter, to make it the “everything app”, similar to China’s WeChat, capable of messaging, streaming, payments and video conversations. But achieving it will need an entirely different company from the one he bought.

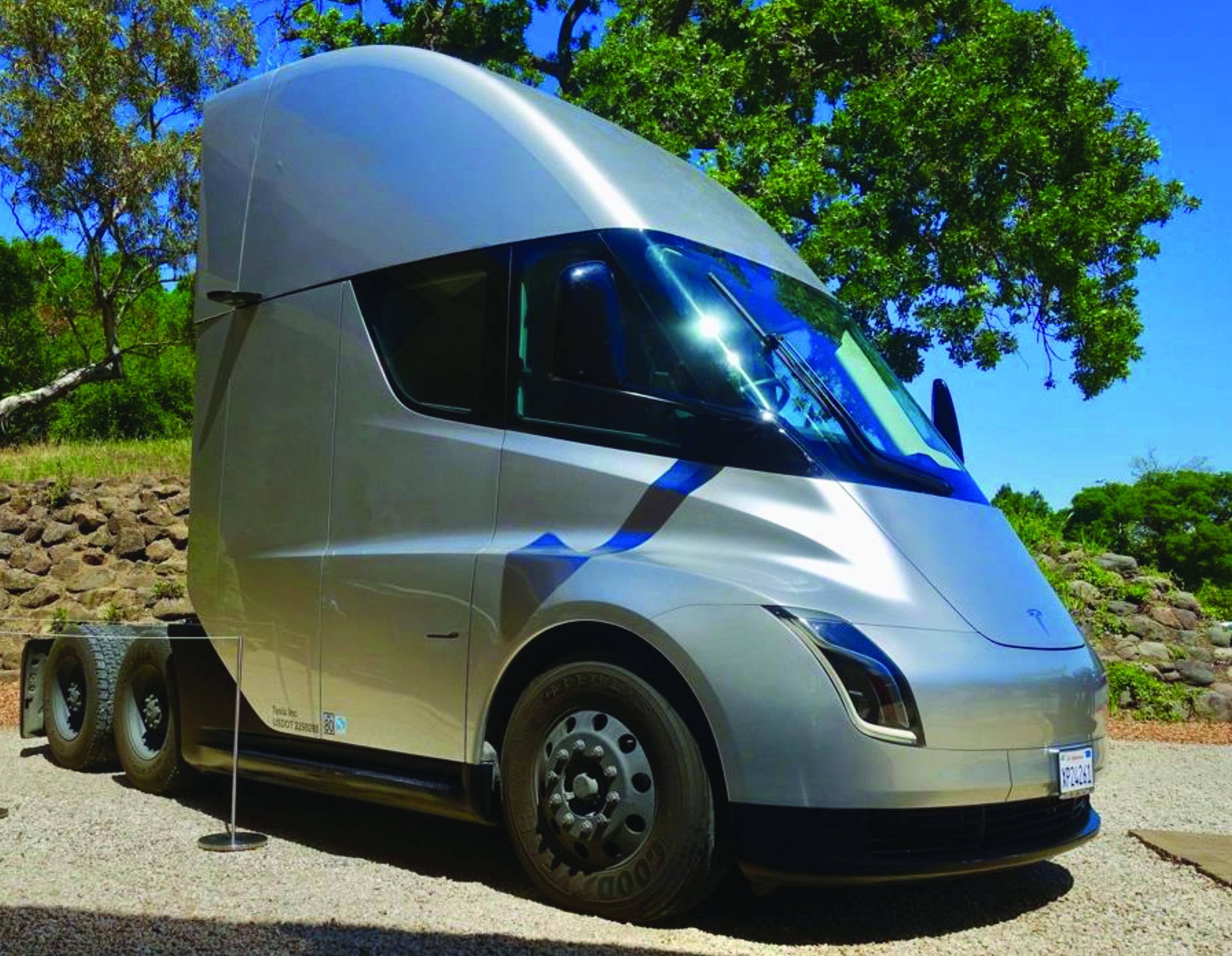

At his other ventures, Musk made announcements which would have been monumental coming from any single company, or single CEO, but fade in Musk’s outsized glare. Tesla delivered its first all-electric semitrailer trucks to PepsiCo. It has taken longer than Tesla imagined to develop and build the trucks, but they have the potential to transform the emissions-heavy freight trucking industry the way Tesla shook up passenger cars. And SpaceX announced that the US government had given it permission to launch 7,500 more satellites to build out the Starlink network, which is already the largest such network ever created.

Source: Wikipedia

Then, as a final palate cleanser, Musk presented the latest updates from Neuralink, his company that is working on brain-chip interfaces intended to help people with damaged neural networks to recover key functions, such as sight, speech and movement. Musk said that Neuralink will be moving from testing on monkeys to humans within six months.

Musk makes a mockery of Flaubert’s advice that one should be “regular and orderly in your life, so that you may be violent and original in your work.” Musk’s personal life is as colorful as his public life.

In the spring of this year, he played a minor role in the lurid court battle between Johnny Depp and his ex-wife, Amber Heard. Depp accused Heard of having an affair with Musk while they were married, an accusation Musk denied. Over the summer, the Wall Street Journal reported that Musk had had a brief affair with the wife of his friend, Sergey Brin, one of the co-founders of Google. Again, Musk denied it, but the Journal stood by its reporting. The back and forth added yet more texture to Musk’s growing reputation as a bounder.

He has had ten children, by three mothers. His first, with his first wife, Justine, died at 10 weeks old from sudden infant death syndrome. In November, Musk wrote on Twitter “My firstborn children died in my arms. I felt his last heartbeat. I have no mercy for anyone who would use the deaths of children for gain, politics or fame.” He was explaining why he refused to allow the conspiracy theorist, Alex Jones, back onto Twitter. Jones was recently ordered to pay hundreds of millions of dollars to the families of the children murdered in a school shooting in Sandy Hook, Connecticut, after he called the shooting a hoax concocted by anti-gun activists.

Justine Musk, however, was having none of Musk’s sentimentality. “Not that it matters to anyone except me,” she wrote in response to her ex-husband’s Tweet, “because it is one of the most sacred and defining moments of my life, but I was the one who was holding him.”

If this is the behaviour of the richest man in the world, what lessons does this offer the rest of us? Should all CEOs be out there carrying sinks into the office and tearing strips off their own employees in public? Tweaking the regulatory authorities and daring them to slap them down, as Musk has done on several occasions by ignoring the rules on when and how to declare his financial interests?

If everyone behaved like Musk, the world would be chaos. Society can only take so many anarchists. But few of them have figured out how to use their freedom the way that Musk has. He has turned his life into a rare kind of performance art, filled with triumphs pulled from the teeth of disaster.

Several biographers have already taken a crack at Musk, but the next will be Walter Isaacson, who has written books on Steve Jobs, Leonardo da Vinci and Benjamin Franklin. There is plenty of material. Musk grew up in South Africa, where he was horribly bullied both at school and by his own father. He came to Canada and then the United States for university, and was demonstrably brilliant even at a young age.

After his early success with PayPal, he spent years working on his electric car and rocket projects, and came close to losing both of his companies. Given his friends, his supporters, and talents, there were so many easier opportunities for him in Silicon Valley. But he chose projects that were brutally difficult both in engineering and entrepreneurial terms. While his peers built software teams for social media start-ups, Musk built factories, solved the most complex hardware challenges, and took on gigantic incumbents, in the form of the car industry and NASA. The many brilliant car developers and rocket scientists who have been drawn to Musk were attracted by the possibility of outlandish progress on projects which had stalled in the bureaucracies where they worked. Musk’s financial success is reward for the scale of what he took on.

Musk’s defenders say that his achievements would have been impossible if he was as chaotic as he seems. He sees the vulnerabilities in the entrenched way of doing things and is strategic about turning those weak points to his own advantage. Even with Twitter, after all the hullaballoo around his takeover, he does seem to be making progress by forcing people to ask difficult questions about truth, news and editorial responsibility in the digital age.

Musk’s rambunctious approach is vastly different from the evasive platitudes offered by the giant search engines and social media platforms, which have tried to minimize their editorial responsibilities for years. It would be remarkable, and yet perhaps not surprising, if from all the smoke and fury a more elegant, and more purposeful Twitter emerged.

Philip Delves Broughton is an author and journalist. He is a Senior Consultant to Brunswick, based in New York. He was previously a Senior Adviser to the Executive Chairman of Banco Santander. His books have appeared on The New York Times and Wall Street Journal bestseller lists and been published around the world and include Ahead of the Curve and The Art of the Sale.