Winter 2022

Russia, China and the US – As Seen by Latin America

In the current geopolitical environment, many Latin American and Caribbean governments have been faced with the dilemma of having to ally themselves with one or several of the three superpowers that exist today. How they go about this is very much dependent on economic convenience and/or geographic reality. The United States’ sphere of economic and political influence does not extend much beyond Mexico and some of the Central American countries and therefore the tendency is to be closer to the US. For its part, China has been focused on expanding trade and investment mostly with the large South American nations, especially Brazil, Argentina and Chile, while Russia has more active ties with Venezuela, Nicaragua and Cuba. In spite of these general alignments, which have been nurtured over the last decade or two, current tensions between the US and China on the one hand, and between Washington and Moscow on the other –especially since the invasion of Ukraine—have pushed the region’s governments to manifest a clear preference for one or other of the superpowers. This has mostly been in economic relations, but also politically after the COVID pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The war in Ukraine produced varying responses from governments in Latin America, as has also been the case with other regions. It is tempting to define Latin American reactions to the war in Europe on the basis of whether individual governments are on the left or on the right of the political spectrum, but it would be simplistic to proceed in this manner. In this brief analysis I will try to show the apparent reasons behind individual country reactions in Latin America, as well as to explain some of the motivations of individual leaders in the region.

Latin America today is mainly governed by populist elected leaders that in most cases represent left of centre ideologies and policies. This is a relatively new phenomenon which comes after several decades of governments that espoused open markets and were by and large supportive of the Washington consensus. In elections held in Brazil, Chile, Peru, Argentina and a few other countries during the last two years, electorates have opted for change and brought into power autocratic, left of centre governments. In several cases such as Lula in Brazil, Boriç in Chile and Petro in Colombia, newly-elected heads of state are former opposition leaders, or even combatants with histories of trying to overthrow previous governments through armed conflict. Elsewhere in the region, although not openly from the left, country leaders are privileging domestic issues such as social inequality, health deficits and low economic growth. Foreign policy and events taking place in other regions of the world tend to be minimized or even ignored by these governments. With their inward focus as a priority, domestic problems almost always take precedence over international events, even those in neighbouring countries.

In the specific case of Russia’s unprovoked attack on Ukraine, reactions in Latin America have been shaped by historical experiences, economic relationships with the major powers involved in the conflict and an overall desire at best to remain neutral. In defining these reactions, the history of United States’ interventions in the region is an important factor. Countries such as Mexico, Chile and Argentina view the Ukraine conflict in the light of those interventions, while close trade and investment ties with Russia, such as is the case in Central and South America, naturally colour the way in which those governments are unwilling to criticize Moscow’s actions publicly. It has been relatively easy for this group of countries to proclaim neutrality on the basis of a false argument: Russia is threatened by NATO and the expansion of the alliance’s membership to countries formerly part of the Soviet Union and now bordering Russian territory. This strategy, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, forced Russia to take defensive measures to protect its western flank. Since NATO was originally intended as a military alliance against the Soviet Union during the Cold War, this argument seems plausible in today’s geopolitical world. In advancing this theory, Latin American governments often see the conflict in Ukraine as a legitimate attempt by Moscow to return its borders to those of czarist Russia, or at least to those of the USSR.

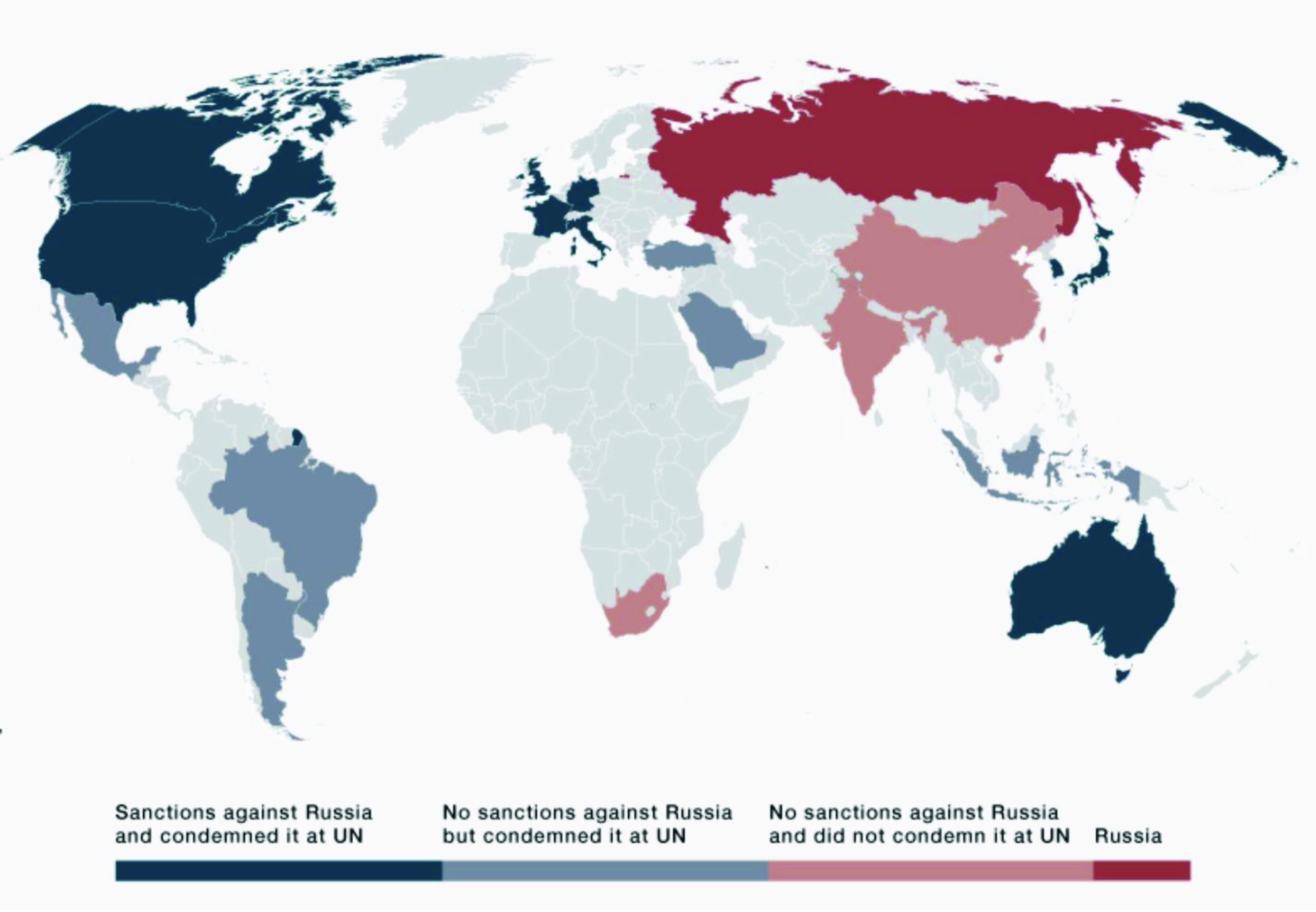

In analysing Latin American reactions to the conflict in Ukraine, it is important to also remember the role Moscow played in the Cuban missile crisis and the lingering relationships that Havana, Caracas and Managua for example, maintain with Russia. Another issue relates to sanctions. Latin American countries have never approved of economic or other sanctions imposed unilaterally outside of the United Nations or Organisation of American States charters. The now 60-year-old US embargo on Cuba and its unanimous rejection by all Latin American and Caribbean countries, together with other historical examples of sanctions imposed by a single country or group of countries, is one of the main reasons that Latin American governments have been unwilling to accept US or other Western country requests to join the unilateral sanctions on Russia for its invasion of Ukraine.

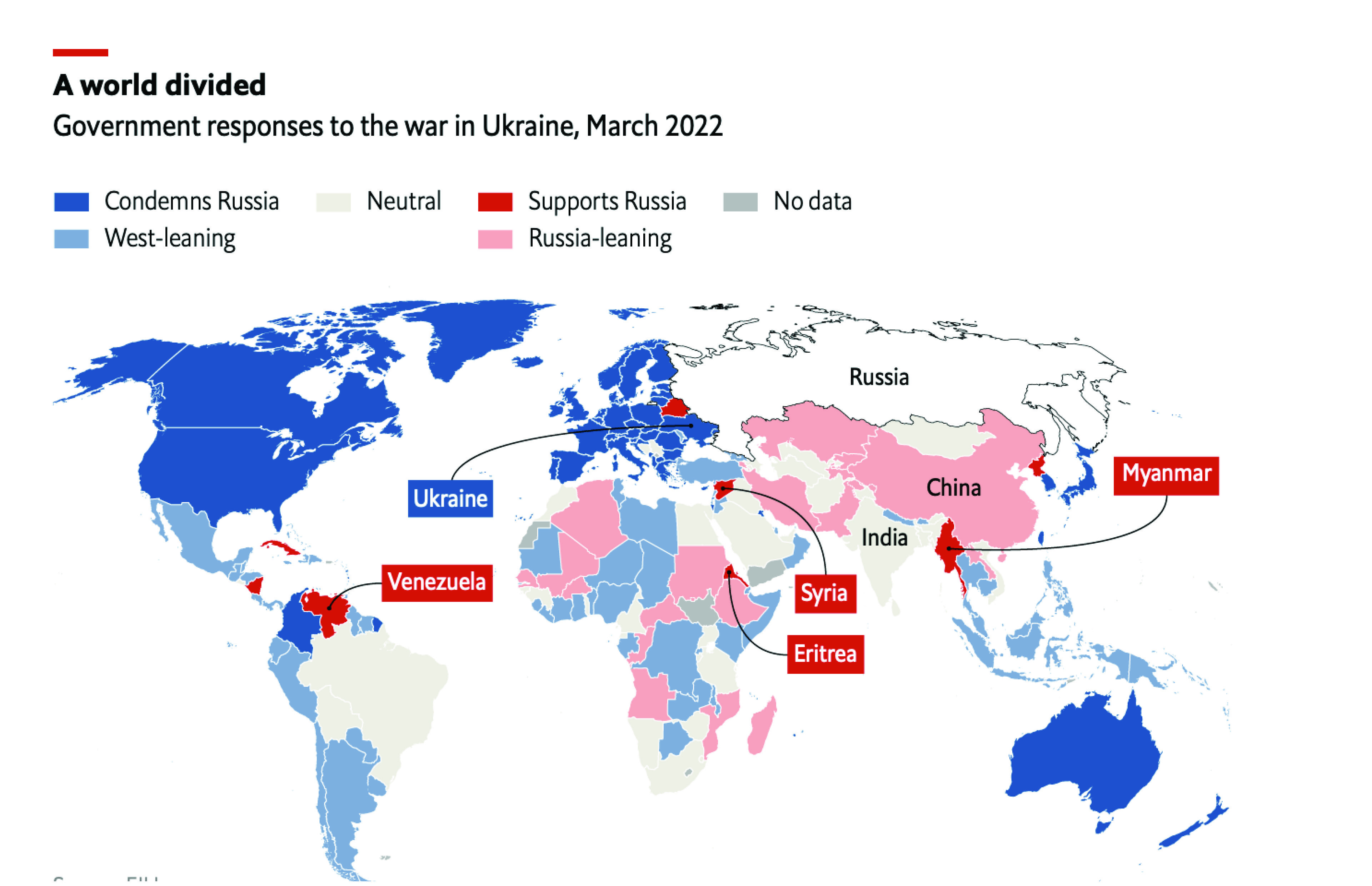

Source: The Economist

Mexico

President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, also known as AMLO, has said that he will follow a neutral path regarding the Ukraine-Russia conflict, although he and his Foreign Minister have been pushing for a negotiated cease fire and eventual peace agreement, most recently at the G‑20 summit in Bali. Mexico’s position has been somewhat contradictory because on the one hand, at the United Nations, its delegation voted consistently in favour of the resolutions adopted by the Security Council and the General Assembly calling on Russia to withdraw from Ukrainian territory, while in speeches and press conferences AMLO has insisted on the country’s neutrality. Historically Mexico has on quite a few occasions decried territorial invasions by one country against another. Having suffered several foreign invasions itself, there is ample justification for a policy that opposes armed intervention, or territorial annexation, in violation of a country’s sovereignty. One of the best examples of this was Mexico’s lone voice at the League of Nations challenging fascist Italy’s unlawful annexation of Ethiopia in 1935. As far as sanctions are concerned, Mexico has made clear that it will not accompany any of those imposed by individual governments without UN approval. In addition, although Mexico does not have extensive economic or investment ties with Russia, AMLO has made clear that any relationships that exist between the two countries will continue unaffected by the war in Ukraine.

Brazil

The reaction by Brazil to the war in Europe is somewhat different from that of other Latin American governments. President Bolsonaro has steadfastly refused to support the UN resolutions and has ordered his representatives in New York to abstain in the voting. Brasilia’s ties with Russia are considerably more important than Mexico’s, yet there has been little desire by the government to risk angering Moscow, Washington or Brussels. In his speech to the UN General Assembly this past September, Bolsonaro also called on the parties in the conflict to find a negotiated peaceful settlement but refrained from placing any blame on either Russia or Ukraine. With Lula’s election last month, it will be interesting to see whether the Brazilian government changes its position starting in January when he takes office.

Chile, Colombia and Peru

These three countries have recently elected left of centre governments, especially Colombia where a former guerrilla is now the country’s president. Chile also has a newly installed leftist as head of state, but President Boriç has maintained a basic neutrality in his public statements regarding the conflict in Ukraine. Peru, with another ideological leftist in power, has also shown no appetite for criticizing Russia. It should be remembered that many countries in Central and South America have strong and deep relationships with Moscow and are therefore loathe to risk annoying the Russians. This in addition to the historical experience that Chile went through when the United States conspired to overthrow the Allende government.

Argentina

The Peronist government in power has generally allied itself with the other left of centre leaders in Latin America. Alberto Fernández is facing an extremely difficult domestic economic and social situation, with a very high international debt and runaway inflation. Nevertheless, the following statement issued by the Argentine Foreign Ministry right after the invasion of Ukraine exemplifies the general Latin American view of the conflict:

The Argentine Republic, faithful to the most essential principles of international coexistence, makes its strongest rejection of the use of armed force and deeply regrets the escalation of the situation generated in Ukraine.

Fair and lasting solutions are only achieved through dialogue and mutual commitments that ensure the essential peaceful coexistence.

The need for full adherence to all the principles enshrined in the Charter of the United Nations, without ambiguity or giving pre-eminence to each other, with full respect for international law and full and deep respect for human rights.

The intensification of the winds of war seriously hinders the urgent objective of preserving life, it is essential that all those involved act with the greatest prudence and de-escalate the conflict on all its edges to guarantee the peace and integral security of all nations.

As a general conclusion, the Latin American region has reacted with one voice to the war in Europe. Although some say that Ukraine is too far away geographically and does not have strong ties with the region, governments in the region are guided principally by history and traditional foreign policy in maintaining their neutrality in this conflict. Public opinion, however, sometimes reacts differently as one hears voices blaming the US and its western allies for provoking Russia into defending its borders with new NATO members that were once part of the Soviet Union and recalling armed interventions by the US and its allies in Afghanistan, Iraq and others. Many Latin Americans have for decades during the Cold War remembered these incursions and strongly believe that the United States has ulterior, unacknowledged and imperialist motives in getting involved in conflicts far from its own territory.

Andrés Rozental holds the lifetime rank of Eminent Ambassador of Mexico. He occupied a number of senior positions in his counter’s foreign ministry including Deputy Foreign Minister, Ambassador to the United Kingdom, Sweden, and Permanent Representative to the United Nations in Geneva. He has held non-executive and advisory Board appointments with numerous multinational corporations, including ArcelorMittal and Ocean Wilson Holdings. He is also Senior Policy Advisor at Chatham House.