Winter 2012

Militant Islam: on the March?

In early 2013, British, French and German troops are expected to deploy to Mali to help train local forces to take on Al-Qaida in Timbuktu: proof, if any were needed, that the whack-a-mole war on terror has become a truly global phenomenon, and that no corner of the world, however remote, is immune to the Islamist menace now.

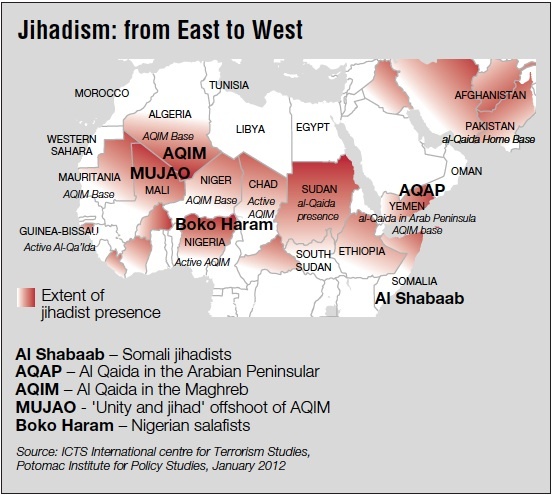

Africa worries some Western military strategists even more than central Asia does these days. Until recently the continent’s only serious Islamic extremist group was Somalia’s al-Shabaab, a self-professed affiliate of al- Qaida, who dominated their country for more than three years until they were driven out of Mogadishu in summer 2011 by the mostly Ugandan troops of AMISOM, the UNbacked African Union Mission in Somalia.

AMISOM’s successes, however, have been tempered by the rise in north and west Africa of a host of other Islamist groups, such as the Movement for Jihad and Unity in West Africa, known by its French acronym MUJAO, and Ansar Dine, an Islamist Tuareg movement from over the Algerian border. These two organisations are presently in control of northern Mali, an area the size of France. Further east, in northern Nigeria, the Salafist Jihadist group Boko Haram – ‘Books Forbidden’ in the Hausa language – was responsible for hundreds of deaths in 2012. All of these groups are armed with weapons stolen from Libya’s armouries during the collapse of Gaddafi’s régime in 2011, and all of them are thought to be linked to al-Qaida’s north African franchise, AQIM (al-Qaida in the Maghreb).

The baleful influence of al-Shabaab, meanwhile, may be spreading, despite further significant territorial losses this year. Kenya, whose army joined forces with AMISOM and attacked al-Shabaab from the south in October 2011, has since experienced a rash of kidnappings, suicide bombings and other deadly attacks, particularly in Mombasa. Some analysts describe the Swahili coast, of which Mombasa is the capital, as the ‘soft underbelly’ of Muslim East Africa, ripe for exploitation by militants inspired by Wahhabist ideas from Arabia. Squeeze a tube of toothpaste in the middle, and it splurges out both ends. With elections due in Kenya in 2013, the fall-out from the Kenyan Defence Force’s first ever foreign military venture could be spectacular.

The West’s greatest security fear is that Africa’s disparate Islamists might join forces against them. In early 2012 General Carter Ham, the commander of Africom, the US Africa Command, warned that groups such as AQIM and Boko Haram were attempting to coordinate their efforts through the sharing of funds, training and explosives; and added that others, including al-Shabaab, could do the same in the future. General Ham repeated his warning in November. ‘If left unaddressed, AQIM will grow stronger,’ he said. ‘They will gain a capability through recruiting and the ability to train in a safe haven. They will develop an increasing capacity to conduct external attacks… and I can without a great deal of imagination envision them extending their range of attacks into Europe and to the United States.’

But is he right? Africa’s Islamists undoubtedly cause significant local instability, but do they really have the capacity to link up and mount 9/11-style attacks against the West in the future – or should this threat remain where General Ham acknowledges it is now, that is, firmly parked in the realm of the imagination?

Islam is on the rise in Africa – massively so, accordingly to the Pew Research Center in Washington, which estimates that there will be 386m African Muslims by 2030, 60 per cent more than the present 242m, representing a rate of increase almost double the projection for the Muslim world as a whole. But these startling numbers do not represent a security threat to the West per se. The growth of Islam should not be confused with the march of Islamism. Besides, the number of extremists among all these African Muslims remains tiny. In northern Mali, according even to General Ham, there are no more than ‘probably 800 to 1,200 hardcore militants ready to fight’ out of a population of 1.5m. The highest estimate for the strength of al-Shabaab, similarly, is put at about 14,000, with a hardcore of perhaps a third of that figure, among a nation of 10m.

In any case, al-Shabaab, still thus far the continent’s most successful Islamic militants, have never looked like an organisation either able or even very willing to link up in any serious way with like-minded foreigners.

Source: ICTS International centre for Terrorism Studies,Potomac institute for Policy Studies, January 2012

In Mogadishu in 2011 there were constant newspaper reports of squabbling between their leaders, who still fundamentally disagree on the future direction of their movement. The hardliner Ali Zubeyr ‘Godane’ is thought to want to export and spread Salafist Wahhabist ideas in the manner of al-Qaida. But Somalia’s Muslims are by tradition peaceloving Sufis, not Wahhabis. Godane is opposed by a relatively moderate and inward-looking al-Shabaab wing, led by Mukhtar Robow, who considers some of Godane’s tactics to be ‘unSomali’ – which may be why, to date, al-Shabaab has mounted just one concerted terrorist attack beyond Somalia’s borders, in Kampala in July 2010, when suicide bombers killed 74 civilians at an open-air screening of the World Cup Final.

In 2011, Godane and Robow were unable to co-ordinate even basic domestic policies, such as how to deal with the drought and famine afflicting the south of their country. Godane’s handling of the famine was certainly not the work of a jihadist genius. His response was to call it ‘infidel propaganda’ and to deny its existence; villagers fleeing the disaster zone were ordered to return to their homes and pray for rain. In a nomadic society, which depends for its survival on moving to greener pastures when the rains fail, this was a public relations disaster.

My own experience of al-Shabaab fighters in Mogadishu in 2011 was that their primary reason for fighting was rarely ideological, and usually more to do with simple survival. At AMISOM’s headquarters I interviewed three recent prisoners, the oldest of whom was 17, the youngest 15, who had put their hands up when an al-Shabaab recruiter had come to their school a fortnight previously; they had decided to surrender when they became separated from their unit and ran out of bullets. Why, I asked, had they put their hands up in the first place? The boys all looked at each other. ‘We were given a piece of fruit every day,’ said one of them.

Fighters for African Islamism, as well as many of its leaders, tend to be young. Violent extremism is mostly a young man’s game. It is no doubt significant that Somalia has a particularly low median age of 17.8 (and probably equally significant that this is about the same as in Afghanistan). Godane, the hardline leader of al-Shabaab – which means ‘the youth’ in Arabic – was born in 1977. His young foot-soldiers are often not just ignorant of the world, but breathtakingly impressionable. One group of recruits being groomed for martyrdom was reportedly shown a Bollywood video and informed that this was real footage of Paradise, sent down to earth by past martyrs for the cause.

The danger of such clueless young people, of course, is that they are capable of any imbecility, including terrorist atrocity abroad. In the years following the failure of US military intervention in Somalia in 1993, American and Western strategy in the Horn as well as elsewhere in Africa was to try to ‘contain’ the Islamist threat. Containment, however, has failed, for one main reason: the immense size and spread of the diaspora. Somalis do not live exclusively in Somalia as they used to, any more than Nigerians or Malians do. The number of Somalis living abroad is estimated at 2m, and of Nigerians, as many as 15m.

‘Somalia represents a kind of threat we haven’t seen before,’ said Matt Baugh, the British ambassador to Mogadishu (who, for security reasons, is still based in Nairobi). ‘There are massive numbers of Somalis living in all the neighbouring states as well as around the world. It is not a traditional, geographical country, but a diffuse, global entity – and that is not physically containable.’

Britain, home to perhaps 300,000 Somalis, has already experienced Somali-linked terrorism on its streets, in 2005. The failed London Transport bombers of 21/7, Ramzi Mohamed and Yassin Omar, were both born in Somalia. The US has had its problems too, notably in Minneapolis, where America’s largest concentration of Somali exiles has settled. Since 2007, at least 48 young American-Somalis are known to have travelled back to Somalia in secret, in order to fight for or train with al-Shabaab. Among them was America’s first ever suicide bomber, Shirwa Ahmed, 26, who blew himself up in the northern Somali city of Bossasso. On the tenth anniversary of 9/11, Congressman Peter King, the chairman of the US House of Representatives Committee on Homeland Security, came to London to warn British MPs that there was ‘increasing evidence’ of terrorist-trained Somali-Americans attempting to come back to the US, where the danger of radicalization had grown ‘much worse’.

The failure of containment leaves only one alternative: engagement with the drivers of the instability on which radicalism thrives, both among exile populations and in their homelands. Al-Shabaab has been able to prosper only in the absence of governance in Somalia, where there has been no proper central control for over twenty years. Permanently defeating al-Shabaab’s reductive brand of Islam will depend on restoring that control, and giving the next generation at least the prospect of what all young people want: education, jobs, security, a home. In Mogadishu, in a government compound set aside for deserters, I came across Abdi-Osman, 23, a former al-Shabaab fighter. Before fighting for the Islamists, he revealed, he had been a pirate. ‘Every man who has nothing will try something to get money,’ he shrugged, when I asked him why.

How many of Africa’s militant ‘Islamists’ are Abdi-Osmans, looking out for themselves and trying to survive? These are people for whom jihadist ideology, and in particular al-Qaida’s Salafist dream of international Muslim cooperation and the establishment of a global Islamic caliphate, comes far down their list of priorities, if it features at all.

![Good news from the Congo: Air Korongo Airlines A good example of Africa’s new ability to create progress out of adversity is the recent launch of Korongo Airlines, which connects Kinshasa with a number of regional capitals better known in recent years for humanitarian disasters than economic opportunities. The following account by journalist Christophe Lamfalussy first appeared in the newspaper La Libre Belgique in Brussels last April: On Thursday morning the irrepressible George Forrest, one of the motors of the Katanga economy and owner of 32000 head of cattle and a private Gulfstream jet, presented to the deputy prime minister the Lubumbashi hangar of his company. His Airbel holding, owner of Korongo Airlines, is a joint venture between Brussels Airlines and Forrest Group International. It aims to open up 30% of its capital to Congolese investors. Open since April, after two years of negotiation with the Congolese authorities, the company currently flies to Johannesburg — a quickly profitable route —- and Kinshasa. The ambition is to become a regional African airline for local passengers: ‘we’ll start soon with connections to Mbuji Mayi’\[ achieved on 31 October\]‘and Kolwezi’ Forrest explains. ‘After that we’ll go on to Kisangani and Goma. Each time we have to adapt the airports to international standards. We’ll go on to connect with Lusaka, Nairobi, Entebbe and Luanda’.\n George Forrest needs the support of Belgium because the European Union has placed all Congolese companies on a blacklist. To get Korongo off this list, the Congo must request a derogation from the EU.\n The arrival of Korongo has been greeted with huge relief, because the risks of an accident are so high with other companies. Embassies and humanitarian organisations are increasingly authorising their staff to use the two Korongo airplanes, a BAE 146 and a Boeing 737. The company is approved by the Belgium and Congolese Civil Aviation Authorities, its maintenance crews are provided by Brussels airlines and Belgium economic assistance has sent three fire engines and six ambulances as back-up.\n Thanks to the rise in prices of copper, cobalt and other minerals in Katanga, Lubumbashi is going through a fabulous mining boom from which Korongo hopes to profit. For the first time since colonial days, there are garden parties in the Katangan capital, the roads are asphalted and the banks are multiplying.\n One of the key players in this spectacular revival is Moise Katumbi, governor of the province. Born in Lubumbahsi of an Italian Jewish father and a Congolese mother from the royal family of Bemba, this 47 year old governor is the owner of the all-powerful football club ‘Tout-Puissant Mazembe,” which won the African Champions League in 2011. Katumbi has become a popular politician in seeking to clean up the corruptions and abuses of the Katanga administration: ‘We had to get rid of the guilty man, and we have done so. What is killing the Congo is the impunity with which people defied the law. We have toll roads around the city, which brought in 300,000 dollars a month when | took over five years ago. Now it’s just under seven million.”\n This Katangan businessman has also asphalted 1000km of highway in five years, a lot more than the Belgians did throughout their time in charge of the colony. ‘We have to direct the Congolese State toward economic development, and not towards guns and ammunition.’](https://montroseassociates.biz/images/uploads/Winter12-5_2.jpg)

The governments of Mali and Nigeria are not as dysfunctional as Somalia’s have consistently been, but have failed nevertheless to offer their young people much chance of a better life. Before the ousting of President Amadou Toure in Mali, the poor had been getting poorer for years while his corrupt administration massively enriched itself through drug smuggling. According to one report, an affluent area of the city of Gao – now under Islamist rebel control – is locally nicknamed Coacaïnebougou.

Corruption among Nigeria’s elite is just as pervasive, and causes just as much resentment among the young. As in Somalia, radical Islam is a symptom of societal and governmental crisis, not its cause – although it often suits corrupt governments to claim the opposite. The Nigerian opposition leader Buba Galadima said recently of Boko Haram: ‘What is really a group engaged in class warfare is being portrayed in government propaganda as terrorists in order to win counter-terrorism assistance from the West.’ The group’s name, he added, had been widely misunderstood. ‘What the Boko Haram people are saying is it is sacrilegious to acquire Western education and to use it to cheat… your fellow human being[s],’ he said. ‘If that is all Western education is about, for you to get into a position of authority and steal from the public treasury, then it is bad.’

His sentiment, surprisingly, was echoed by the former US ambassador to Nigeria, John Campbell, who told Voice of America: ‘The Nigerian government is… treating Boko Haram as a security problem. But I see it more as a political problem, and rather than focusing so much on police methods, I would try political initiatives that might have the potential for sucking the oxygen out of Boko Haram.’

If Campbell is right, then a solely military Western response to the emerging threat of radical Islam cannot be appropriate. In Nigeria and Mali, a policy focused on engagement rather than containment means what the West has belatedly begun to do in Somalia: state-building through a sustained commitment to political, social and economic reform.

Thanks in part to Western pressure, Somalia recently elected a new president, the former university professor and UN consultant Hassan Sheikh Mohamud. For the first time in 20 years, his cabinet was appointed not according to the old clan power-sharing formula but on technocratic merit. The message was heard among the country’s diaspora, so many of whom have begun to return home that parts of Mogadishu are experiencing a minor property boom.

It is, paradoxically, to the diaspora young that the West should turn for salvation from the threat of Islamism. To the host countries, the diaspora is a double-edged sword. Communities in exile can be hiding places for terrorists as well as breeding grounds for home-grown ones. In 2011, when Prime Minister David Cameron described Somalia as ‘a failed state that directly threatens British interests,’ the first threat he cited was that posed by the radicalization of young Somali Britons.

And yet the Somali diaspora is also a rich sump of educated and reform-minded talent. In Somalia’s case, a whole generation have grown up in the West who are out of patience with the old ways of doing things. The best of them have taken advantage of the opportunity to better themselves through work and education, absorbing Western values and ideas along the way; and an extraordinary number of them are movingly determined to export their ideas back to Somalia in order to help rebuild their troubled homeland.

They should be the West’s partners of choice in any African nation-building project. And although General Ham’s warnings of a pan-African Islamist link-up can not be ignored all together, these should be taken with a pinch of salt. Preparing for the worst is what soldiers do; it does not mean that it is going to happen. Our future security will depend on civilian engagement as much as and maybe more than on military containment. The threat posed by African Islamism is too serious to be left to the military to address on their own.

James Fergusson is author of In Search of the River Jordan: A Story of Palestine, Israel and the Struggle for Water published by Yale University Press