Winter 2012

Zimbabwe: Endgame in Sight?

A drive down several of the roads on Harare’s perimeter provides a startling depiction of the state of Zimbabwe’s economic and political condition. Miles and miles of adjacent enormous villas in grandiose nouveau riche style, each one probably worth well over US$ 5 million.

It is puzzling in a country that produces so little, where its traditional industrial base is moribund, unemployment is over 90 percent, electricity and water supplies are highly erratic, where it is extremely difficult to fire labour, transport networks are badly run down, and so on.

Banks and building societies are incapable of providing loans on anything near this scale. The only possible explanation for nearly all of this glaring wealth is corruption, limited to few thousand apparatchiks of President Robert Mugabe’s ZANU-PF party, as well as a much smaller, but growing number of officials from Prime Minister Morgan Tsvangirai’s Movement for Democratic Change (MDC).

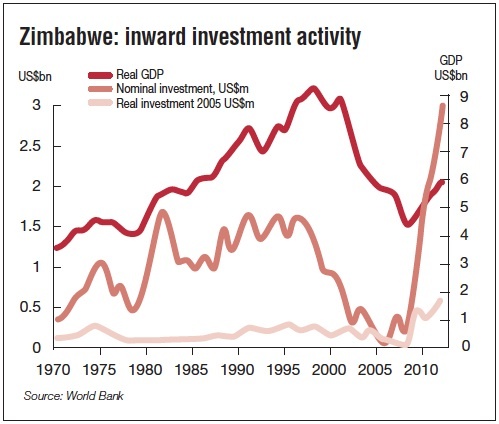

Zimbabwe’s broken economy finally shot ahead in early 2009 with the abolition of the local currency, denominated in trillions, and its replacement mostly by the US dollar. Foreign investment surged after more than a decade of dormancy.

The coalition government was almost exactly a year old on February 9 2010 when the investment boom came to an abrupt halt. Regulations enforcing the “indigenisation” law passed in 2006 forced foreign and white businesses to “cede” 51 percent of their shareholding to black Zimbabweans on pain of a five-year jail term and forced acquisition.

Chinese companies have been spared this amputation of their ownership by political protection. However, major foreign investors like Implats and Angloplats have entered into indigenisation agreements with the government, and have survived.

The replacement of the word “cede” in the regulations for “purchase” has made it obligatory for indigenous wouldbe owners to actually pay for their shares. With the unlikelihood of any of them meeting the payments of the billions required, major companies feel they can relax, for the time being.

The precise details of the big indigenisation agreements reached have not been published.

Source: World Bank

Opacity is certain to conceal fat payoffs to satisfy the ministers, deputy ministers and officials involved. Already there have been reports of community shareholder trusts set up by the companies being plundered by local officials.

Zimbabwe is home to one of the world’s richest diamond deposits at Marange in its eastern Manicaland province. Diamonds from the four companies exploiting Marange were looked to as the saviour of the shrinking economy, but what has turned up in the fiscus in taxes, royalities and dividends, is a tiny fraction of the potential.

The accounting from Marange companies and government departments involved is entirely opaque. However, it cannot conceal the highly visible, rapid accretion of wealth by members of the Mugabe circle, like mines minister Obert Mpofu, who on a small official salary has emerged as one of the country’s richest ministers.

The Toronto-based rights group Partnership Africa. Canada estimated in a November report that $2 billion in diamond earnings have been stolen since 2008. “The scale of illegality is mind-blowing,” it said. In another damning report, the pressure group Global Witness identified Anjin Investments, one of the world’s biggest diamond producers which was operating in the field as a Chinese-Zimbabwean joint venture part-owned and partcontrolled by Zimbabwe’s Ministry of Defence, the military and police.

Low-level bribes and backhanders also extract a major toll. Transport companies say enforced bribes at police roadblocks (38 on the 450 km stretch between Harare and Bulawayo, by one count) now cost as much as their fuel bill.

Corruption ensures loyalty of the officials in strategic positions and, just before elections, buys votes. This is referred to locally as “Mugenomics”. Despite his economics degree, the president who has held power since white-minority rule ended in 1980, betrays no hint of awareness of the effects of squandering money. Shortterm political gain is his sole object.

Elections under a new and significantly more democratic constitution are due by the end of June when the five-year life of the current parliament expires, and with it the coalition it has supported. Mugabe is perfectly capable of stalling elections beyond June, when he would be able to hold them under the old constitution, to his advantage.

here is no doubt that under another term he would continue in exactly the same way. He has already been insisting that the threshold for indigenised ownership should go to 100 percent. A Mugabe victory would produce another economic collapse before too long.

A decisive victory for his main rival Morgan Tsvangirai and the MDC would certainly be different. It would create a wide range of democratic reforms. Probably the most significant change would be the removal of an administration whose hallmarks are cruelty, vindictiveness and violence.

The MDC is incompetent and blundering and occasionally violent, but not committed to control by fear. The prodemocracy roots adopted by the MDC were completely absent in ZANU-PF from the party’s start. The blockade against foreign investment could be expected to be significantly reduced, although it would be too much to expect a complete dismantling of indigenisation, or of Mugabe’s seizures of agricultural land from 2000 onwards which led to the collapse of the economy.

It would also be naïve to expect a new firm line to be taken against corruption. The government of national unity exposed the MDC’s leading lights for the first time to easy money, large backhanders and expensive cars at state expense. There is no doubt MDC mandarins are among the villas on Harare’s outskirts. “They’ve learnt well at the trough,” is a much-heard remark.

The new bling among the MDC hierarchy being seen by their mass of poor supporters is certain to affect the party’s strength in a relatively free and fair election.

The MDC’s biggest liability now is Tsvangirai. The Central Intelligence Organisation’s honey-trapping of the increasingly hapless leader led him into a highly embarrassing dalliance that cost him $300,000 in a court settlement with a rejected bride. He is now seen as distracted by the affair, and now his subsequent marriage, when his undivided attention is essential to his dealings with the wily Mugabe in complicated constitutional and election issues.

However, these factors are more likely to increase apathy than to turn voters to ZANU-PF. MDC voters have proved in the five elections since 2000 that they have long memories of economic ruin under ZANU-PF and deep scars from violence.

ZANU-PF is in a state of inertia, dominated by aged deadwood, including defence minister Emmerson Munangagwa and presidential affairs minister Didymus Mutasa. Its division between supporters of Munangagwa and vice-president Joyce Mujuru is potentially fatal.

ZANU-PF’s only attempt since 2000 to switch from brutality to peaceable vote-buying, in the first round of the 2008 election, failed miserably.

So it is unsurprising to hear the Zimbabwe Peace Project, the most reliable barometer of political violence and intimidation, report that violent incidents in October increased by 50 percent. Mugabe’s recent emotional appeals for peace and tolerance can be safely ignored.

Source: Gallup

It is well known that campaigns of violence are closely managed by the Joint Operational Command, the committee of military, police and intelligence chiefs which is chaired by Mugabe. He turns it on and off.

The last six months have seen regular statements from generals and brigadiers, culminating with army commander Lieutenant-General Philip Sibanda, asserting that “foreigners and their puppets” – ie., the MDC – will not be allowed to “reverse the gains of our liberation struggle.”

It is difficult to know if these are serious, or part of the general pattern of frightening the electorate into compliance. However, a classic coup d’état need not be necessary to ensure ZANU-PF stays in power. The involvement of the military in the murderous campaign before the run-off presidential run-off elections in 2008 was as close to seizing power as it needed to be, and could easily be repeated.

There are indications they intend to again. Steady deployment of troops, often in plainclothes, into rural areas has been reported for months. Earlier this year military chiefs met and discussed how military intelligence units could work with specialist soldiers across rural areas to secure an election victory for Zanu-PF. These orders were coming directly from General Constantine Chiwenga, the commander of the Zimbabwe Defence Forces who has been known to have declared that if Zanu-PF loses elections , then the military would take over and assess the consequences later.

The only major obstacle in ZANU-PF’s path is the Southern African Development Community (SADC) which is empowered to act as the guaranteor of open and transparent elections. Mugabe’s only supporter left in the regional organisation is Zambia’s President Michael Sata, and he sounds increasingly less committed. A ZANU-PF régime installed – again — by violence certainly would not result in a military reponse from SADC, but more likely diplomatic and even economic isolation. Whether a desperate régime already in conflict with its African critics would be affected by such censure is unlikely.

Underpinning all this is Mugabe. ZANU-PF internal politics revolves around the issue of the succession, i.e., who will succeed him when he dies.

It is an old-fashioned African political game in which it is understood that the leader is ever-watchful for signs of ambition for his crown among his court. Ambition is a sign of dangerous disloyalty and invites swift political retribution. It results in each of the secretly contesting figures engaging in a competition to be more sycophantic than the other.

Hence the constant declarations by Munangagwa and Mujuru of their adoration for Mugabe, and denials that they are interested in the presidency, while Mugabe and everyone else are kept fully informed of the constant shift in the two opposing factions. In this way Mugabe has maintained total control over ZANU-PF for 35 years.

Mugabe has again, for the ninth time since independence in 1980, been nominated as ZANU-PF’s sole candidate to lead the party into the next elections. It means that he has no qualms about campaigning for elections next year, aged 89, and knowing that theoretically his term will end when he is 94.

He travelled 10 times last year to Singapore for medical treatment that was never disclosed but which is presumed to have been for a serious condition. This year he has shown himself to be fit, articulate and mentally nimble as ever. His mother lived into 100 years. But he may well drop dead at any point.

It will trigger a frantic scramble between Mujuru and Munangagwa for the presidency, and potentially serious political and economic instability. Mujuru’s position has been weakened by the sudden death last year of her husband Solomon Mujuru, one of the most influential and respected figures in Zanu-PF.

The charred remains of the liberation hero and former army commander were found after a suspicious fire destroyed his farmhouse in Beatrice 50 miles south of Harare just a short time after he had arrived from Harare. Mujuru was one of the few Zanu-PF leaders with the stature to stand up to Mugabe and there was no love lost between him and Munangagwa. There is a widespread belief he was murdered.

There is great anxiety that the successon could be bloody, involve the military and result in a repressive rogue state with less credibility than Mugabe had.

It may equally lead to the collapse of ZANU-PF, already weakened by internal strife. There is a tendency by many to overestimate ZANU-PF’s capacity for organisation and operations. It is not a highly efficient, close-knit organisation capable of quick decisions and action. It has repeatedly bungled with major political operations and been shockingly misinformed. It reacts ponderously to situations. It is riven from the top down with petty jealousies and plotting. What has kept it going is having a sole, single-minded leader, Mugabe.

The breakup of the party would, after a complicated process, result in presidential elections. There is little doubt that without Mugabe, ZANU-PF would not stand a chance in a relatively free and fair vote.

Then Zimbabwe, with its educated workforce, infrastructure superior to anything outside South Africa and economy in the doldrums waiting for investment, may begin to reconstruct itself to be part of the economic growth seen in so many other African countries.

Jon Swain is an award-winning former foreign correspondent for the Sunday Times who covered the Vietnam War. His memoir River of Time is available in all good bookshops.