Summer 2013

No Silver Bullet: The Shale Revolution and US-Gulf Relations

The prospect of North America turning from a net importer of crude oil to net exporter is the most important shift in the geopolitics of oil relations in recent years. It has served two purposes. The first is to undermine the fear that global oil production will peak soon, for if North America can reverse a 50-year trend of declining domestic oil production the same could happen elsewhere in the world. The second is the possibility of a fundamental shift in Washington’s engagement with the Middle East and the Arabian Gulf.

Opinion in the Gulf is divided. One school of thought maintains that not much will change. A second sees the shift as a serious and imminent threat. A very prominent proponent of the latter line is Saudi Arabian Prince Alwaleed bin Talaal al-Saud. His widely publicised letter of May 2013 to Ali Al-Naimi, Saudi Arabia’s oil minister (who falls firmly into the first camp), presented the situation in stark terms. “The world’s reliance on OPEC oil, especially the production of Saudi Arabia, is in a clear and continuous drop,” he wrote. Alwaleed went on to argue that the Kingdom should diversify its sources of revenue, while increasing its capacity to utilize other forms of energy, particularly nuclear and renewable sources.

Others have focused on political implications, predicting that a United States no longer dependent on Saudi oil would reduce or abandon its historical commitment to the security of the Arab Gulf states, even suggesting that America would be freer to criticise the Gulf’s governments on other topics, including human rights and democracy.

While denying the impact of the turnaround in North American oil production may seem simplistic, there may be reasons to doubt that it will bring all the consequences hypothesised. A more critical consideration of the realities of the crude oil market suggests that important consequences are to be expected. They just may not be those suggested so far.

Source: author’s elaboration on data from EIA

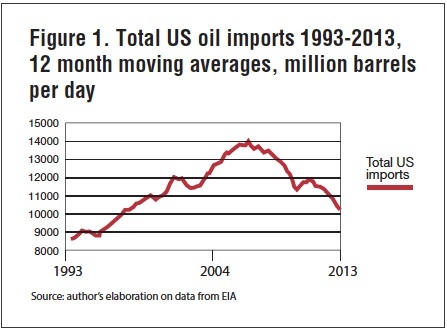

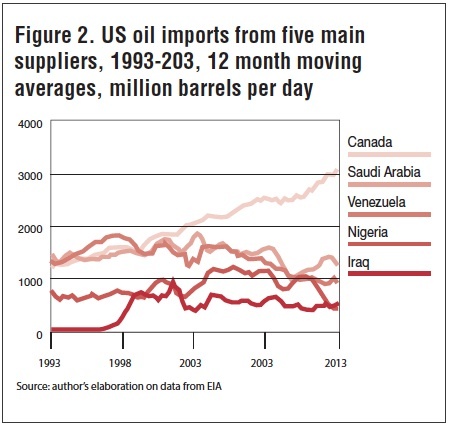

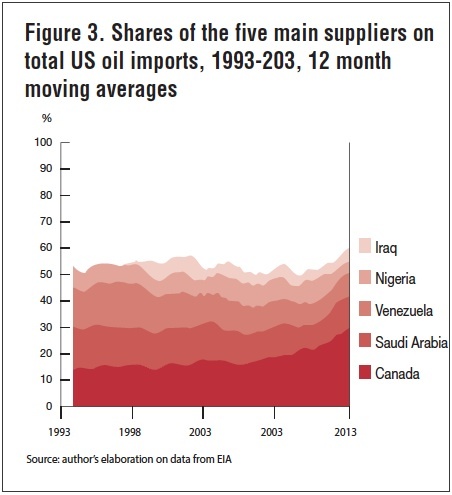

US oil imports peaked in 2007 and declined thereafter. The decline came from a combination of increased domestic production and declining demand from the economic crisis and the substitution effect on American energy consumption habits provoked by higher oil prices. The composition of imports by country of origin also evolved. Imports from Canada have increased systematically. Canadian oil production is increasing. Its potential for further expansion from non-conventional sources is even more significant than that of the United States. Limitations in available transportation infrastructure mean that today essentially all Canadian oil is exported to the United States, meaning that Canadian producers receive prices that are much lower than going prices for similar quality seaborne crude oil. These limitations are bound to be overcome in time. Canadian producers are keen to diversify their markets and obtain better prices for their oil. This could lead to a decline in their exports to the United States.

All remaining major exporters to the United States have registered declines over the course of the last decade. Of the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), Saudi Arabia is the only significant exporter to the United States. The Kingdom has almost invariably occupied second place, after Canada, as a source of US oil imports. While Iraq became an important oil source for the US in the late 1990s, with Saddam Hussein in power, it has declined since the American-led intervention and régime change. Other GCC countries like Kuwait and Abu Dhabi are not important US sources of oil, while Iran’s sanctions régime continues to rule it out.

Saudi oil exports to the United States fell to their lowest levels in the immediate aftermath of the economic crisis in 2009, but have since recovered. Iraq’s share is small, but has remained stable in recent years. This is in stark contrast to Venezuela and Nigeria, both of which have declined precipitously, partly because of the increase in US shale oil production.

The American dynamic can to be explained in the light of refinery economics and control. Oil is not imported by the government. Refineries decide where to source their oil from, and it is to refineries that we must look to understand what determines US oil imports. Two aspects are important. First is the global competitiveness of US refineries. Second is control, particularly Saudi Aramco’s ownership of American refineries.

Source: author’s elaboration on data from EIA

Aramco first invested in US refining in 1989, when it entered a joint venture with Texaco covering refining and distribution assets. When Texaco was taken over by Chevron, Aramco and Shell bought Texaco’s interest and now share ownership of the JV, Motiva Enterprises, on a 50–50 basis. In 2007 the partners embarked on an expansion of Motiva’s Port Arthur refinery in Texas, raising its capacity from 285 thousand to 600 thousand barrels of oil a day. Port Arthur became the largest refinery in the US, configured specifically to allow for the refining of heavier Saudi Arabian crude oil.

Saudi Arabia produces four grades of oil: Extra Light, Light, Medium and Heavy. The share of the latter is growing as new fields are developed and production from older fields is reduced. Arab Heavy is also the least valuable and sometimes difficult to market as not all refineries can process it. This was the situation in 2007, when prices were increasing rapidly and Saudi Arabia was accused of producing too little oil. All the while, Riyadh kept repeating that oil was available and the shortage was in refining capacity. Hence the Port Arthur expansion is directly related to Saudi Arabia’s wish to satisfy US demand independent of shortcomings in the configuration of independent refineries.

Details of the contractual arrangements between Motiva’s partners are not known. So, it cannot be said with absolute certainty that the refinery is 100 per cent committed to treating Saudi crude. However, it is reasonable to assume that this will be the case. Complex arrangements must be in place to ensure that Saudi oil is sold to the refinery at competitive prices, while also ensuring that the refinery does not make excessive profits thanks to its access to cheap crude. It is also likely that Motiva is paying the same price as all other importers of Saudi oil, but Aramco uses the information it gets from Motiva management (distinctively non-Saudi, although Aramco has representatives on the board) to manage the differentials it sets to the Argus Sour Crude Index that it uses to price crude oil into the United States.

A refiner’s decision concerning the source of its feedstock is its own. Washington has no routine legal tool to influence it, and it would also have no clear interest in doing so. There is therefore no reason to expect that political considerations will interfere with the decision of Motiva and other US refiners to continue importing Saudi heavy crude as long as Saudi Aramco continues to price the crude competitively for the US market.

Aramco and Shell do face a challenge; refineries with access to domestically produced light shale oil currently enjoy much better margins. However, Motiva’s refineries have the advantage of being able to treat less expensive and heavier crude oil. In contrast, some of America’s Atlantic refineries are facing difficulties as logistic bottlenecks hinder access to cheaper domestic light oil. This has led to a rapid increase in transportation by barge, rail and even truck.

US refiners have enjoyed a historically positive competitive position relative to the global industry, which has led to an increase in American exports of oil products. This is expected to continue, meaning that the United States may well continue to import crude oil while also exporting larger volumes of oil products. This evolution would be in line with the overall “reindustrialisation” effect, expected from the availability of cheaper shale oil and gas, along with the revival of petrochemical and other energy intensive industries that have been in decline for years.

The point is clear. Although political discourse emphasises “oil independence”, the priority for the American industrial system is not independence, but maximizing corporate revenue and profits. The latter is likely to be better served by continuing imports of crude oil coupled with increased exports of refined products, petrochemicals and other energy intensive goods.

Source: author’ elaboration on data from EIA

It may then be said that the United States is no longer dependent on oil imports, in the sense that the latter might be curtailed and domestic demand satisfied. But this has almost always been the case. The United States never was truly dependent on any supplier, including Saudi Arabia. The case might be made that imports from Canada would be difficult to substitute, but no one expects Canada to suddenly turn off the taps to the United States.

That said; there is no indication that Saudi or indeed Gulf oil might become redundant. If economic growth slows down in the BRICS and other key emerging markets while failing to pick up in the OECD, it is possible that global oil demand might grow less than expected, or not at all. This could create conditions of oversupply for OPEC oil, on the assumption that member countries produce at their full quota or target level. But this assumption is not likely to be met. Iran remains under sanctions, Libya has seen its exports plummet because of domestic dissent. Iraq is making less progress than expected, while Nigeria and Venezuela are slipping. For the time being, Saudi Arabia is again increasing production. In July it was back above 10 Mb/d to compensate for a shortfall in Libyan production. It is worth remembering that it fell as low as 9.15 Mb/d a day at the beginning of 2013.

Thus, Alwaleed’s claim that “the world’s reliance on OPEC oil, especially the production of Saudi Arabia, is in a clear and continuous drop” is factually incorrect, although it seemed more plausible when the letter was written in May. The United States can hardly be indifferent to Saudi Arabia’s political stability, because any serious threat to the same would have disastrous consequences for the global economy. The same can be applied with respect to any of the major producers in the Gulf. It is only in the unlikely event of a major détente with Iran and return of Iranian oil to global oil markets that the equation might change.

The Prince’s policy indications, nevertheless, remain valid and are widely shared within Saudi Arabia itself. It is clear that the government is excessively dependent on oil revenue, and vulnerable to a possible (indeed likely) decline in prices – although other producing countries would suffer even more. It is also clear that Saudi Arabia and other GCC countries should diversify their domestic power generation fleet to include renewable sources and a nuclear component. But neither of these aspects is directly related to shifts in US oil production.

At this moment, American policy towards the greater Middle East appears to be in disarray, with events in Syria, Egypt, Iraq and Afghanistan posing dilemmas to which no clear answer seems forthcoming. This has created significant disillusionment in the Gulf, and repeated calls for greater regional cooperation and less passive dependence on Washington’s leadership. Nevertheless, GCC members are themselves at odds on the strategic direction of their policy. Their tools are limited to the money and weapons that they can allocate to supporting various parties in the conflicts convulsing the region, with little assurance of success. So, the GCC will always need the US, and vice versa.

Reluctant as it may be, the involvement of the United States in the region is not primarily related to “dependence” on Saudi oil. In fact, it has never been primarily motivated by US import needs. It is not less likely to endure nevertheless, because of the significance of the region for the global economy and the multiple ties that have developed between Washington and the Gulf’s capitals over the last five decades. In the end, no one can be indifferent to what happens in the Middle East.

Giacomo Luciani is an expert on energy geopolitics teaching at the Paris School of International Affairs (Sciences Po) and the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva. His latest book Security of Oil Supplies: Issues and Remedies was published by Claeys and Casteels in January 2013