Summer 2013

The Middle East: A Failure to Deal With Change

It looked like a film played backwards: the sight of a military helicopter carrying Hosni Mubarak flying over the dusty rooftops of Cairo from Tora jail to a military hospital. It is as though nothing had changed. We had gone back to conditions that existed before his ignominious fall in February 2011.

Yet that is not the case. True, the army and police have restored the security state that had held Egypt since the 1952 coup swept the army to power. The Muslim Brotherhood leadership have been rounded up, thrown into prison, and are on the brink of being outlawed as they were throughout most of their existence. But for all the brutal efficiency of the counter-revolution, the clock has not been turned back, and nor can it.

Two elements have changed above all. First, the movement of mainly young people expressing their opposition to the status quo in 2011 has not evaporated. Over 18 days they created pressure to which the army yielded in removing President Mubarak. They showed the power of the new technologies and social networking sites to mobilise. The movement, made up of disparate groups, may have seen first “their” revolution snatched from them by the Muslim Brotherhood and then reversed by the subsequent army intervention. But the genie is out of the bottle. It cannot be put back. The people have learnt that they have power. The army listens to the mob. And the mob is volatile. Its current support for the army can quickly change.

Source: United Nations, World Population Prospects: The 2004 Revision New York: UN, 2005.

Second, political Islam emerged as a major force. The Brotherhood may now have to regroup after it was forced from governing. But it remains the single largest political organisation within the country. Over the past thirty years, Arab society has become ostensibly religious, more wedded to the idea of a role for religion in the political sphere. The Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt have shown disastrous incompetence in governing Egypt. However their failure does not signify their demise.

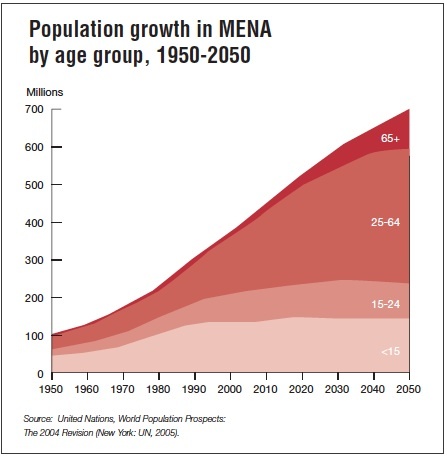

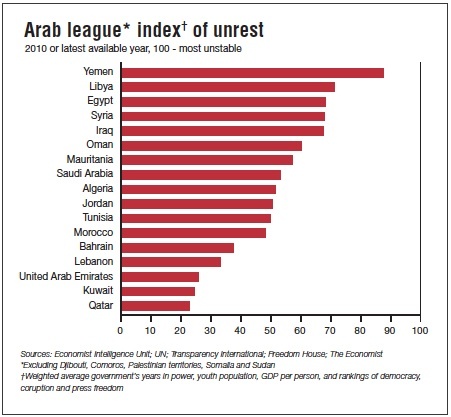

What has not altered in Egypt and in all the Arab states is the response of the political authorities to change. For most, their default position is to confront it, not to embrace it. In most states, the authorities seek to maintain the status quo. What has emerged over the past few years is a depressing sight: an increasingly youthful population seeking change and a political class incapable of the vision to imagine how to satisfy their demands. This growing divide between aspiration and lack of satisfaction is storing up even greater trouble for the future. Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states two years ago sought to forestall any similar upheaval of the disaffected young. They increased state handouts, the share of oil revenues to be distributed to their citizens rather than kept among their ruling families. Yet all states were buffeted by the waves sweeping across the region. Kuwait is a failing state. Social unrest rocked Oman. There the Sultan responded by sacking most of his ministers associated with financial incompetence or tainted by rumours of corruption. The UAE has acted decisively to counter what it regards as a threat from the Muslim Brotherhood. They have other issues too, with the Shia uprising in Bahrain providing a particularly troublesome test for other autocratic regimes. And Iran, the major power in the region, other than Saudi Arabia, remains a fervid, troubling presence. The election of an apparently more amenable president has done little to allay the fears of Iran’s Gulf neighbours, especially Saudi Arabia and Abu Dhabi, that it harbours nuclear ambitions that could threaten the entire region. Not all Arab states are the same, but many of their shortcomings are common to them all. Even before the upheavals that became known as the Arab spring, each and every Arab state was faced with similar challenges: the demographic pressures of a rapidly expanding population the gap between ruler and ruled the inequable rule of law the increasing influence of Islamism or political Islam In addition the UN Human Development report identified three other factors holding the region back: poor education, absence of freedom, and the failure to harness properly the potential of one half of society-women.

Source: Econom intellegnce Uinit; UN; Freedom House; The Economist

The regional population continues to rise unabated. Indeed, the rate of increase in the population in Egypt actually rose for the first time in decades in the year after the fall of the Mubarak régime. The population of Saudi Arabia is set to double by 2050. That of Yemen – already short of water and resources – is set to overtake Saudi Arabia’s around the same time. There may be nearly 300 million Arabs now. Within a generation that figure will be nearer 500 million.1 The numbers are staggering. The implications are breathtaking in terms of demand on resources, on water, on energy, for building schools and homes and hospitals. And above all creating jobs, to find productive work for a largely unqualified workforce to undertake.

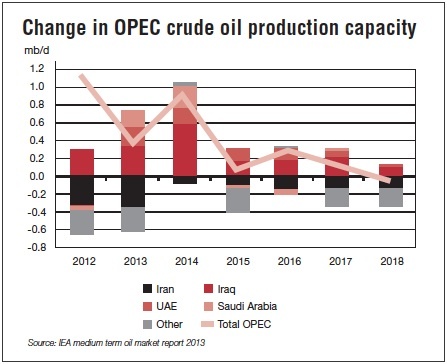

The massive projected rise in population has implications also for governance. In the absence of proper institutions, the people of the Arab states depend heavily on personal contact, on tapping into those with patronage, to address grievances and redress wrongs and to obtain favours. That system might function after a fashion with smaller populations. It inevitably widens the gap between ruler and ruled when played out on a larger scale. Furthermore, the systems that have existed for generations might not be suited to modern life for other reasons. At the simplest level, how is a system to accommodate the aspirations and desires of 19 different sons of the last ruler of Abu Dhabi and president of the United Arab Emirates, the much-revered Shaikh Zayid Al Nahyan? Succession is an issue in each and every state but nowhere more so than in Saudi Arabia, the only country in the world named after its ruling family. The eventual death of King Abdullah will lead sooner or later to the next big but very difficult step in the modern history of the kingdom, the anointing as monarch of the next generation, the first king not to be one of the sons of Abdul Aziz (Ibn Saud). The Arab nation is already divided into more than a score of states, with Arab minorities too in Israel and Iran and communities across Europe and the Americas. A number of the states created after the dismemberment of the Ottoman empire are already no longer effectively operating as single units: Iraq, Libya, Syria. The absence of a central authority, or its inability to ensure its writ extends throughout its territory, obviously creates a legal and political minefield for International Oil Companies. Those intrepid IOCs which have ventured into those areas of northern Iraq controlled by the Kurdistan Regional Government still face uncertainties over whether they will ever be paid for oil produced, and how much, given the lack of resolution with the central government in Baghdad over revenue sharing. In addition, political instability and the simmering insurgency by disaffected Sunni Arabs is believed to be behind recent attacks on the main oil export pipeline causing physical impediments to monetising oil produced in addition to the wrangles with Baghdad. Syria has become a cockpit of regional intrigue and international power diplomacy. Saudi Arabia and Qatar have variously supported Sunni Islamist groups opposed to the ruling Alawites, a heretical Shia sect, while the United States and Western Europe waited on the sidelines fretting at the continued support for the Al-Assad régime from Russia and Iran. At the time of writing, the House of Commons had rejected UK government attempts to join a coalition of the willing to take action against the Al-Assad régime. Syria has also become the international cause for young militants, as Spain was for Europeans in the 1930s and Bosnia, Iraq and Afghanistan became for young Muslims. Fighters have come from across the Muslim world to join the international jihad, including from non-Arab Chechnya. Young men from France and Britain, some of them of Syrian origin but often not, have joined several of the groups waging jihad against what they regard as a murderous and oppressive régime. There is a risk of spill over and blowback. Already neighbouring states – Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey – have had to cope with the immense humanitarian tide engulfing them, with millions of refugees displaced by the fighting. Mainly middle class Kurds, who prospered like so many ethnic and religious minorities under the al-Assad régime, have fled north to Kurdish areas of Iraq away from the areas controlled by Al Qaeda and the equally fanatical Jabha al- Nusra. The prospects of a settlement in Syria look distant. The country is increasingly in the grip of warlords. There is also a high risk that mujahideen will be so radicalised they will perpetrate acts of violence in their home countries on their return. The conflict in and over Syria has sharpened the divide between Sunni and Shia and increased concern in some of the Sunni heartlands, particularly Saudi Arabia, Jordan and Egypt, of the promotion of a Shia crescent from south Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, and Iran with sizeable communities in Kuwait, Bahrain and the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. One unintended consequence of the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2004 – and there were many – was the increased Iranian influence in Iraqi politics and the ascendancy of the Shia majority after the long domination by the minority Sunni Arab population. But there is another conflict within Sunni Islam itself, most evidently seen in Libya and Egypt, being played out between those broadly speaking of the Ottoman, inclusive, more Sufi strain of Islam and the more closed, intolerant Arabian, brand of Salafi Islam. These are what have come to be called transnational challenges, or more strictly speaking, challenges that cross borders that increasingly look like the relics of imperial cartographers. For the major oil and gas producers in the Arabian Peninsula, the external environment is also changing, possibly more swiftly than they recognize. The oil producers club OPEC only very belatedly in May commissioned a report on the long term implications of the production of shale gas – although some industries like the Saudi giant Sabic were quick to see the attractions of cheap feedstock for petrochemicals.

The fact that within a couple of years the United States has gone from an importer of gas to being self-sufficient has had a major impact on the world gas price. As so often with technological advances, such as the development of deep water offshore oil in the North Sea in the 1970s, the Arab oil producers consider the development of shale gas as too expensive and too far away to have any significant impact on them. They are wrong. It is transforming the US economy, and feeding into a great sense of resource nationalism in the US and the desire to maintain energy self-sufficiency.

While it is true that development costs are inevitably higher than in the Middle East, those costs are falling rapidly. Arabian producers are also looking increasingly to eastern markets, particularly in the burgeoning Chinese economy, to account for increased production. However increasingly Arab oil and gas producers are being forced to burn more and more oil and gas at home for power generation. Less available for export will reduce revenues – and weaken OPEC as an effective cartel. Other than Qatar, most of the states of the Arabian Peninsula are long on oil and short on gas. A generation ago, the single unifying theme of the Arab world was support for the Palestinian issue and hostility towards Israel. The Palestinian cause has not disappeared but so many other issues have now taken pride of place. The region is in turmoil. The real heavyweights of the region, the historic capitals of Mecca, Baghdad, Cairo and Damascus, have seldom looked more unstable. And the underlying challenges of governments, the biggest of which is to provide enough for the material and spiritual wellbeing of their peoples, are likely to get bigger rather than smaller. 1 Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2103). World Population Prospects: the 2012 RevisionCharles Richards is a writer and consultant on the Middle East.