Resilience

Solidarity or Social Distance? Lockdown Lessons From the Poet Larkin

The pandemic and all that has come with it represents the most profound shock to our society since the Second World War. Perhaps 9/11 or the Boxing Day tsunami of 2004 bear comparison — but they were sudden faraway dramas watched on television by the rest of the world. The coronavirus, by contrast, is everywhere and invisible and its evil mission goes on and on, its death toll well into the second million, its preventative vaccine months away for the vast majority. It has changed politics, economics, values, norms, prospects and the way most of us work. But has it changed human nature — or taught us a new understanding of ourselves?

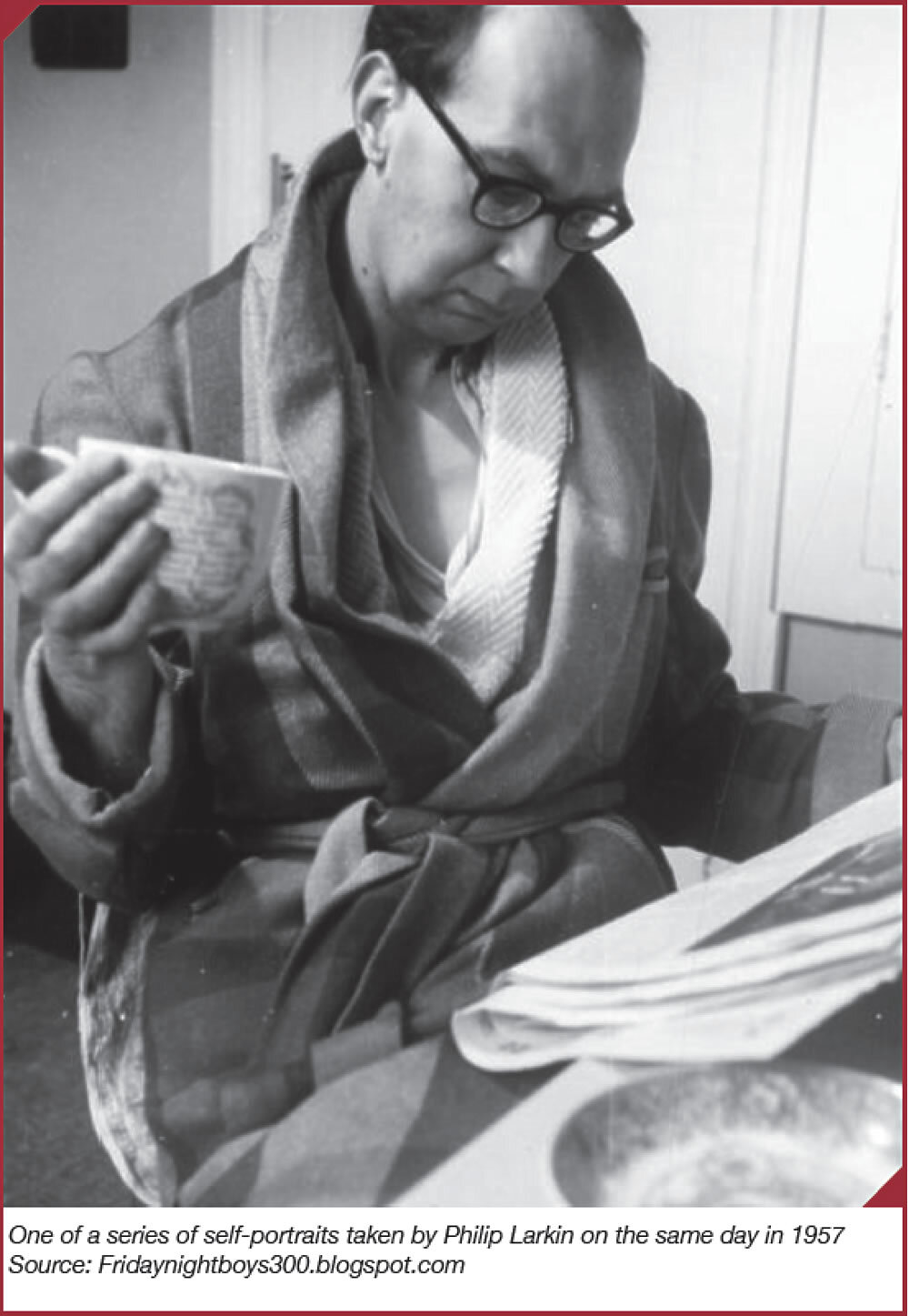

That’s a wide question — with many answers, because let’s not pretend 2020 has been the same for all. Even within neighbourhoods, it has been very different for the frail care-home resident, the cash-strapped small-business owner, the bus driver whose family lives in a crowded block — and the middle classes with their gardens and wine cellars and pensions. But some experiences have been universal, or at least congruent: the need to fall back on inner resources, the urge for solidarity in response to threat, and the sense of death’s proximity. In all of these, poetry can surely help – and the poet who comes to mind, though dead these past 25 years, is Philip Larkin.

It was Clive James, another wry poet-observer, whose ‘Valediction’ celebrated Larkin’s ‘bleak bifocal gaze’ and ‘quiet voice whose resonance seemed vast’. That voice, James wrote, left us…

… less depressed –

Pleased the condition of the human race,

However desperate, is touched with grace.

And grace — in its meaning of virtue and ultimate peace, God-given or otherwise — is one thing we’ll all hope to have found inside ourselves at the end of this crisis. More down-to-earth, James also reminded us that Larkin lived in Hull, the place that in much of his work ‘…stood for England, England for the world’. With its desolate streets, shuttered pubs and peak coronavirus case rate of 780 per 100,000 citizens, as bad as any in Europe, it has done so again this autumn.

A plague on his home town is one reason why Larkin would certainly have self-isolated. But he would have done so with relish: listening to jazz, toying with phrases, dismissing the idea (in ‘Best Company’) that it’s ‘much better [to] stay in company’…

… The wind outside

Ushers in evening rain. Once more

Uncontradicting solitude

Supports me on its giant palm;

And like a sea-anemone

Or simple snail, there cautiously

Unfolds, emerges, what I am.

How lucky to be able to retreat into introspection and emerge the better for it. How many have lived the pocket cartoon by Barry Fantoni in Private Eye illustrating a gag from Peter Cook, of two men at a party, one saying ‘I’m writing a novel’, the other replying ‘Neither am I’?’

Source: Fridaynightboys300.blogspot.com

There are of course plenty who have loved lockdown — ornithologists, astronomers, off-grid self-builders, bitcoin investors, the list is varied. But I suspect they’re far outnumbered by those who have chafed at their own inability to stay focused on long-cherished creative projects, who regret countless nights of Netflix when they could have been learning Spanish, who have been perturbed by their susceptibility to online obsessions — of which the least harmful has been the seductive appeal of estate agents’ website, fuelling (with the help of Rishi Sunak’s Stamp Duty cut) a summer surge in the property market.

Many too have found themselves fatter rather than fitter after months of relative inactivity, more prone to reach for the corkscrew at lunchtime and the gin bottle at six. I think of a retired civil servant’s wife who told me on the phone: ‘Alex is busy digging a hole.’ ‘What for?’ ‘To bury all the wine bottles we’re too embarrassed to put in the recycling.’

So that’s the first divide in lockdown psyche, between the contentment and the frustration of self-realisation. The next, between individualism and collectivism, is much more important in the sense that it will, I predict, form the next great politic-economic debate, the successor and cousin of big-state Keynesianism versus small-state laissez-faire.

Anti-lockdown individualists found their guru in former Supreme Court judge Lord Sumption, lecturing de haut en bas on liberty, and their anti-hero in Dominic Cummings with his rule-bending, up-yours outing to Barnard Castle. Collectivists by contrast self-righteously conformed to each new restriction, finding mutual comfort in appeals for solidarity from leaders such as New Zealand’s prime minister Jacinda Ardern, with her talk of ‘a team of five million citizens’.

And that divergence goes further. Across the Atlantic, it has been personified by Trump versus Biden and the issue of mask-wearing. In caricature, individualists believe tax cuts and rampant capitalism — plus, over here, a no-deal Brexit — offer the best route to renewed prosperity, while collectivists want higher welfare, higher taxes on the rich, and climate change action. A thoughtful first text on these themes is Greed Is Dead: Politics After Individualism, published in mid-pandemic by the economists Paul Collier and John Kay. Echoes could be heard in former Bank of England governor Mark Carney’s first Reith Lecture on BBC Radio 4 at the end of November, with its call for a return to the supremacy of ‘human values’ over financial value.

And it’s fair to say the collectivists have had the better of the argument so far, for the simple reason that that risk of infection from asymptomatic Covid carriers made the individualists’ stance, however principled, look socially irresponsible. Still I think Larkin would have sided with the latter — and it’s hard to picture him stepping out to ‘clap for carers’, let alone bang saucepans and wave cheerily to distanced neighbours. More likely he would have aligned himself with Alan Bennett, addressing the social worker who tells him she has him down as Miss Shepherd’s ‘carer’ in The Lady in the Van:

I hate caring. I hate the thought. I hate the word. I do not care and I do not care for.

And yet of course we know that wasn’t meant in an uncaring way — and what these two writers share is the sense of detachment and irony encapsulated by Bennett in his play An Englishman Abroad, about the spy Guy Burgess:

‘Joking but not joking. Caring but not caring. Serious but not serious.’

Has that essential English trait — so puzzling to foreigners but so often admired — been lost in lockdown? Or was it already lost a generation ago, when the death of Diana Princess of Wales unleashed a new age of lachrymosity in which all must share the grief and pain of others? Certainly the BBC has reinforced that shift these past nine months. No bulletin complete without a weeping relative of the deceased to balance the dryness of science. And the traditional antidote of laughter in adversity has also failed: what woke comedian dares joke about coronavirus?

All of which brings me to my last piece of lockdown psychoanalysis: has the pandemic changed our attitudes to death? In modern times, we’re told, death had become more distant and more sanitised than it once was, encountered (other than violently on television, where it wasn’t real) only a handful of times in a long lifetime and even then rarely with an open coffin in the family parlour as it once was. But now those daily graphs and tearful bulletins have made it ever-present. The former poet laureate Carol Ann Duffy (in ‘The Dead’) gave us this prepandemic cameo:

They’re very close to us, the dead;

us in our taxis, them in their hearses,

waiting for the lights to change.

But this year they have felt far closer than that passing encounter, at times as though we were caught in a jam of corteges and one-way ambulances. A minority of cool rationalists shook off that feeling, quoting parallel numbers for flu or cancer and pointing out that Covid was mostly depriving the elderly ill of their last months, not whole lives. But a great majority, including many of the individualist persuasion, will have shared the gnawing, early-dawn fear so perfectly expressed by Larkin’s ‘Aubade’:

Unresting death, a whole day nearer now,

Making all thought impossible but how

And where and when I shall myself die.

That poem ends with Larkin’s most chilling image — ‘Postmen like doctors go from house to house’ — but not his last word on death. That’s to be found in ‘The Mower’, a miniature gem and a lesson in empathy, which is perhaps the thing we all hope to have found more of, along with a glimpse of grace, during this horrible pandemic. Here it is in full:

The mower stalled, twice; kneeling, I found

Philip Larkin, ‘The Mower’

A hedgehog jammed up against the blades,

Killed. It had been in the long grass.

I had seen it before, and even fed it, once.

Now I had mauled its unobtrusive world

Unmendably. Burial was no help:

Next morning I got up and it did not.

The first day after a death, the new absence

Is always the same; we should be careful

Of each other, we should be kind

While there is still time.

Martin Vander Weyer is editor of Spectator Business.