Resilience

Covid-19 in Japan: How They Did It Better

Many western governments have evaded awkward comparisons with countries that have managed the virus better by dismissing them as too different to learn lessons from – too authoritarian, too geographically isolated, too conformist, too communitarian, even too hygiene obsessed. Yet such attitudes have become less tenable as it has become clear that the countries that have succeeded in best controlling mortality rates are actually highly diverse on all those political or social dimensions.

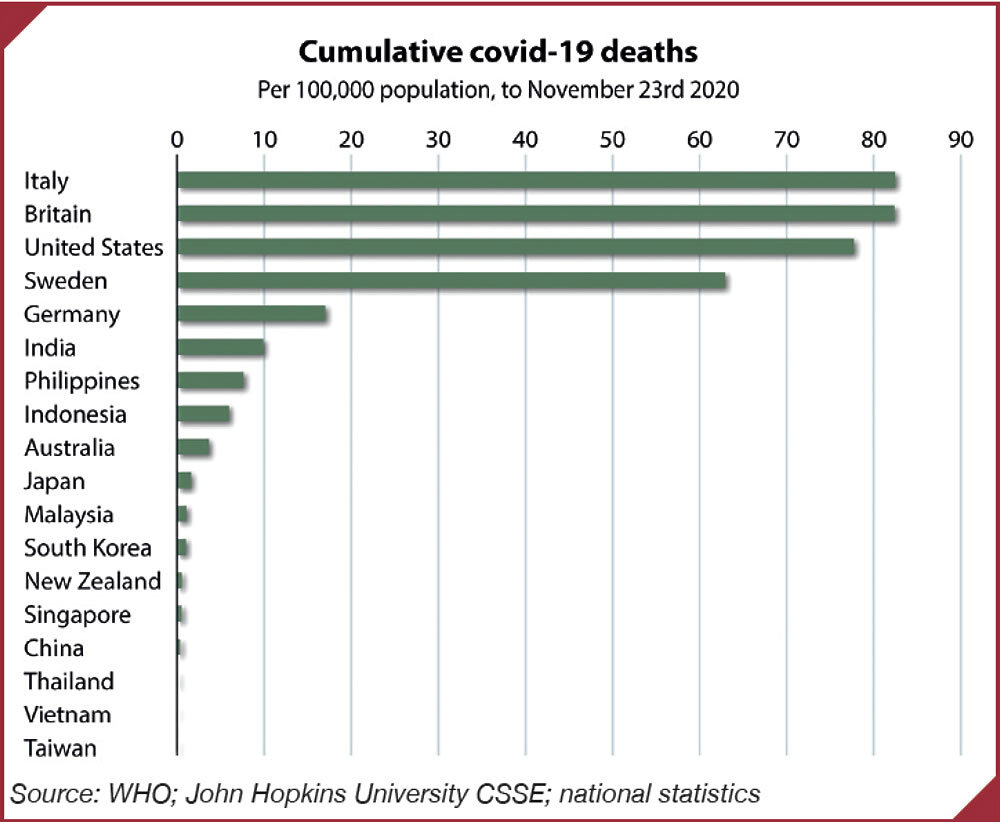

This suggests that there may after all be structural and policy lessons to be learned if a success story can be found with sufficient similarities to your own. Every country in East and South-East Asia – from Indonesia to Vietnam, from Japan to the Philippines, from Thailand to China – has fared better in its health outcomes than virtually any country in Europe or North America. Yet for the advanced countries of the West, one stands out as most readily comparable. That is Japan.

Japan cries out for use as a comparator because of its size (120 million people) its level of development (GDP per capita in 2019 of US$40,000, roughly equal to both the UK and France) but above all its demographics. It has the oldest population structure in the G7, with 28% over the age of 65; Italy has 23%, Germany 21%, France 20% and the UK 18%. It boasts the highest share of centenarians in the population of any country in the world, with over 70,000. It has a much higher population density than any of those European countries, with two especially large, crowded cities in Tokyo and Osaka. It has an abundance of flight connections with China and receives tens of millions of Chinese tourists every year. All of that stood to make it vulnerable to a pandemic such as Covid, which originated in China, which has spread in crowded places and the majority of whose victims have been the elderly.

In February and March, Japan looked likely to become one of the earliest and worst-hit countries. Its first case, detected on 15 January, was a traveller from China. In early February it had the debacle of cases on the cruise ship Diamond Princess, which thanks to administrative paralysis sat moored at Yokohama full of sick people and was widely described as a ‘petri dish’ for Covid. The first locally acquired cases were found on 13 February.

Source: WHO; John Hopkins University CSSE; national statistics

Ten months on from that shaky beginning, Japan is the 2020 coronavirus catastrophe that has not yet happened, even if nothing can ever be guaranteed. As of 7 December, Japan had had 162,917 confirmed cases and 2,259 deaths, with a mortality rate of 1.79 people per 100,000 population, according to Johns Hopkins University’s database and definitions. The United Kingdom, with a population slightly more than half as big, had had 1.72 million confirmed cases, 61,342 deaths and a mortality rate of 92.26 per 100,000 population. Even Germany had had 1.19 million cases, 18,989 deaths and a mortality rate of 22.9, the latter being 12 times higher than Japan’s.

Certainly, Japan has some pre-existing cultural conditions that have helped limit the virus’s toll. Mask-wearing has long been a well-established social practice at times of colds and other ailments, even indoors as well as on public transport. The culture is conformist, with rules enforced by peer pressure more often than officialdom. A preference for bowing over handshakes, a taboo against social kissing and a widespread scrupulousness about cleanliness and hygiene will all have helped. So has a low level of obesity and one of the world’s longest health-adjusted life expectancies.

Against that, however, Japan also had two big disadvantages. Its cities are the epitome of crowded spaces. No one who has seen a rush hour subway train, complete with white-gloved staff cramming passengers into trains, can doubt this. Sporting events and concerts are as crowded as anywhere else. Japan’s bars and restaurants also specialise in throngs and cosiness. You may not kiss the person next to you at the Yakitori counter, nor shake their hands, but you are certainly up close and personal.

And that is even without dwelling upon the hostess bars and other night-clubs of areas such as Tokyo’s Kabuki Cho where close contact is the business model.

The second big disadvantage is its large elderly population and tight-knit family traditions. Just as in Italy, the generations tend to live close to one another in Japan, even if less often in the same house as in the past, and grandparents play a major role in looking after children.

Notoriously, wives are still expected to play a big role in taking care of the in-laws. In Lombardy, the parts of Italy blessed by some of the best hospitals in Europe, the virus spread rapidly and fatally in February, March and April in part because younger generations passed the virus on to parents and grandparents.

Yet this didn’t happen in Japan, at least not yet. So, what went right and what lessons can be drawn for other countries? Three elements of Japan’s success can be highlighted.

The first, which has been widely praised by virologists worldwide, has been good, clear communications about the necessary social behaviour. In late February and early March, when the first official coronavirus task force was set up, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare came up with a slogan which proved brilliantly simple and effective. It was taken up and amplified in particular by Yuriko Koike, the governor of Tokyo, which is important since Tokyo is one of the world’s largest cities, with 13.5 million people in the official metropolitan area but a total of 38 million in greater Tokyo.

What the officials came up with is the slogan ‘sanmitsu’, which is a typical piece of Japanese wordplay, building on shared Kanji characters and sounds and resonant of a Buddhist mantra: people were thus exhorted to avoid mippei kukan, or closed spaces, mishu basho, or crowded places, and missetsu bamen, or close contacts. The sanmitsu is generally referred to in English as ‘the three c’s’. Such simplicity and clarity seem to have struck a chord, helped no doubt by the conformist culture. In many ways other government communications were a lot clunkier, especially over welfare payments, and there was a much-criticised promise by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to distribute free masks to every household, which went badly awry. Two of the ‘buzzwords of the year’ just announced by publishers have been sanmitsu and Abenomasks, the latter being a satirical criticism of that prime ministerial failure.

The second element of Japan’s success has been its focus on tracking down clusters of infections. The coronavirus task force caught on early to the fact that the virus was being transmitted by super-spreaders. But what mattered most in managing quickly to track and trace such clusters was an existing structure of 460 public health centres and, in particular, to the more than 7,000 public health nurses who work there. These centres date back to the 1930s and the effort to track down and eliminate tuberculosis. What they meant was that, just as crime is kept low in Japan partly thanks to a community-based policing structure, with ubiquitous local koban or small police stations, so there is also a community-based public health system, with the public health nurses well known and trusted locally and with deep knowledge of the community.

These 7,000 nurses, as well as a further 40,000 public health nurses working in such places as municipal centres, schools and hospitals played a central role in contact tracing. Definitions of nursing categories vary making comparisons imprecise, but to put this in proportion, on official figures in England there are 350–750 public health nurses and 11,000 health visitors. That may be why while England resorted mainly to an out-sourced, call-centre based track and trace system with little success, Japan’s public health nurses have been far more successful at sleuthing and catching outbreaks before the infection growth turns exponential.

The third element lies in Japan’s elderly care homes. The first level of response protecting the elderly must have been strict adherence to the sanmitsu within families. But just as important has been the success of care homes in protecting their residents. According to figures reported in the Washington Post on 30 August, to mid-June 45% of American Covid deaths and 41% of Britain’s had taken place in care homes, while just 14% of Japan’s much lower total had done so. While fewer than 1% of Americans reside in care homes, the figure for Japan is 1.7%, which means about 2 million people. Those care home residents were safeguarded pretty much immediately, with family visits truncated and even stricter cleanliness standards imposed. Thanks to compulsory Long-Term Care Insurance, introduced in 2000 and covering everyone over the age of 65, Japan’s care homes are among the best funded in the world, and so have a professional nursing staff.

The Japanese like things in threes: good communication, community-based public health nursing, and protected care homes. Certainly, one can add a fourth ‘c’ mentioned earlier, which is harder to replicate, namely conformism, which will have helped hugely. But all the other three can be considered by other countries as they think about how to plan for and hopefully prevent future pandemics and other bio-threats.

Bill Emmott is Senior Adviser on Geopolitics at Montrose Associates. He was Editor-in-Chief of The Economist for thirteen years and former Chair of the Japan Society and the International Institute for Strategic Studies. He is author of Rivals: How the Power Struggle Between China, India, and Japan Will Shape Our Next Decade and his most recent book is Japan’s Far More Female Future, published in Japanese by Nikkei in July 2019 and in English by Oxford University Press in 2020, author of Deterrence, Diplomacy and the Risk of Conflict Over Taiwan (2024).