Summer 2012

The Real Risk-Takers: What Makes an Entrepreneur?

Entrepreneurship has become a fetish in this age of austerity. Governments say it is the key to job creation and growth. Large companies say entrepreneurial management is the only way to stay innovative enough to outrun technological change and disruption. And for individuals, to become an entrepreneur is to give oneself the chance to pursue one’s creative and financial dreams far from the crumbling, hopeless infrastructure of corporate life.

Two main forces are driving this love-in with entrepreneurship. The first is the collapse of decades worth of certainties around work. Not even the Japanese believe any more in the job for life. Loyal employees in their fifties now find themselves thrown onto their own resources long before retirement. Anyone graduating from university in the past fifteen years had been told to expect to have several jobs during their careers, and to keep burnishing their ““personal brand”” for the inevitable moment when they will have to go it alone.

They can toil away for years hoping to become a CEO at 50, or make the entrepreneurial leap and hope to make your millions by 35. Even weighted for probability, the latter seems to many a more invigorating choice.

The second force is technology. One person with a credit card and a computer can now set up a business which ten years ago would have required hundreds of thousands of pounds worth of infrastructure investment and salaries. Global markets of talent, services and customers are accessible at a keystroke. Building a business still takes hard work and gumption. Getting one started isn’t the slog it used to be.

But for all the focus on the economic phenomenon of entrepreneurship, it’s still unclear what exactly we mean by it. Walk the streets of Palo Alto, Brooklyn or Shoreditch, and you might think that all it takes to be an entrepreneur is a pair of skinny jeans, a Macbook Air and a taste for artisanal coffee.

Peruse the business bestseller lists and you will find the likes of Richard Branson and Alan Sugar describing entrepreneurship as a game for a certain type of blustering, blistering buccaneer with an abbreviated formal education and no patience for over-intellectual niceties.

Talk to a corporate executive and entrepreneurship is catch-all term for a set of behaviours most regard as antithetical to large organisations: risk-taking, creativity and what Keynes, in his description of the animal spirits which motivate economies, called “the spontaneous urge to action rather than inaction, and not as the outcome of a weighted average of quantitative benefits multiplied by quantitative probabilities.”

Entrepreneurs, according to this perspective, are the opposite of the cautious planners and spreadsheet jockeys who bedevil big companies.

Earlier this year I spoke to the head of human resources at a large money management company, which had begun life as a hedge fund and since grown into a full-blown financial institution. His greatest challenge, he said, was retaining the “entrepreneurial spirit” of the company’s founders. How was he to find, hire and develop the kind of go-getters who built the firm once it became the kind of large organisation entrepreneurs would rather leave than join?

What was not clear to him or to me was the kind of entrepreneur he wanted: a creative destroyer with the social skills and adolescent fashion sense of Mark Zuckerberg? A carnival barker like Sugar? Or just someone capable of working within a large organisation, yet with that Keynesian spontaneous urge to action? Each is very different.

Over the past three years, I have studied lots of entrepreneurs, the seasoned and successful, the failures and those just starting out.

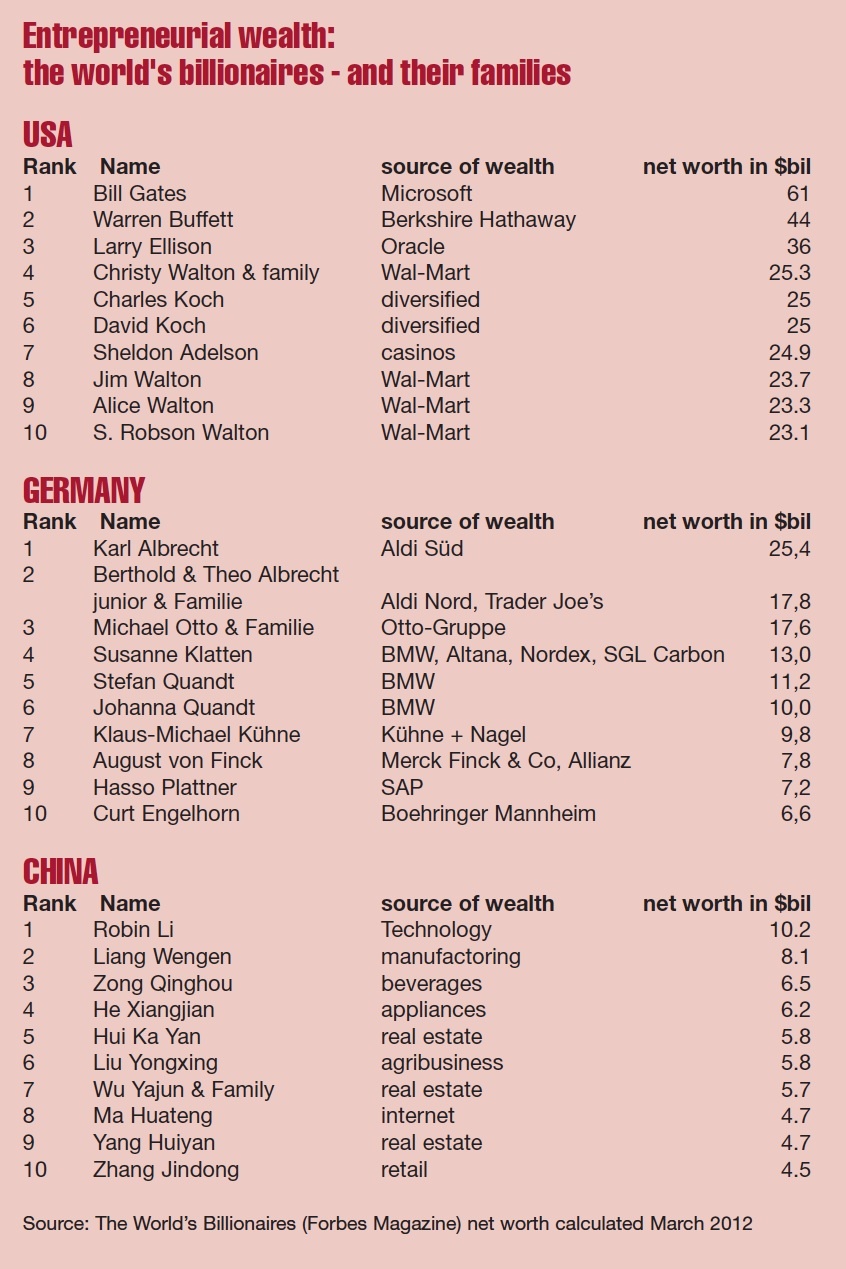

Source: The World’s Billionaires (Forbes Magazine) net worth calculated March 2012

As a researcher at the Kauffman Foundation for Entrepreneurship and Education, and in writing a book about salespeople around the world, I came to the conclusion that trying to describe the “entrepreneurial type” is a mug’s game.

I met entrepreneurs who were introverts and extroverts, men and women ranging from teenage tech wizards to 50 year olds with long corporate track records starting their first business. There were those who were funny and wildly creative, and others who loved nothing more than grinding out the numbers and lines of code shielded from the world by their headphones. Some were motivated by a hunger for professional freedom, others by boiling resentment.

The American media mogul, Barry Diller, once said that his former boss Rupert Murdoch “is at his best…when he is cornered or when he does have great adversity going against him. And maybe it’s his moment of greatest pleasure.” But not every entrepreneur is so aroused by the threat of extinction.

Successful entrepreneurs, I found, tend to have the same traits as most successful individuals. They are fiercely ambitious, hard working and dogged in pursuit of their goals. They make things happen when others give up. But beyond such banalities, their experiences are often vastly different.

Roman Abramovich’s empire building in the rubble of post-Soviet Russia has little in common with experience of the founders of the British e‑tailer Ocado. A wildcatter in the Dakotas has a very different set of problems from an app developer in Silicon Valley.

All are entrepreneurs. But you may as well say that Barcelona’s soccer players and the beer-swilling contestants for the world darts championship are all sportsmen. It’s true but unhelpful. You could spend the rest of your life reading books and articles claiming to identify the traits of successful entrepreneurs, and come away knowing less than you can learn from J. Paul Getty’s simple recipe for business success: “rise early, work hard, strike oil.”

Much more useful, then, than hunting for traits and behaviours is to seek to understand what it is an entrepreneur actually does.

One widely accepted description of the entrepreneur was coined by the Harvard Business School professor, Howard Stevenson. He said that entrepreneurship involved “the pursuit of opportunity without regard to resources currently controlled.”

This describes well the improvisational challenge of entrepreneurship. First you have an idea but no money. Then money but no people. Then people but no customers. Then the money runs out and the idea doesn’t work, but suddenly a customer asks for something similar to but not exactly what you offer, and you’re off again. The entrepreneur is constantly seeing opportunities then assembling the necessary resources on the fly.

What makes us still think of Rupert Murdoch as an entrepreneur decades into his career is that he still seems to crave being at the centre of the action, constantly pursuing and being pursued, chivvying banks, shareholders, employees and politicians to join in the fun.

Conspicuously absent from Stevenson’s definition is the word risk. Entrepreneurs do not covet risk, but seek to minimise it by sharing it with investors, partners, employees and customers. They do this through persuasion and salesmanship, which is the most important business talent an entrepreneur must possess. If they cannot de-risk the pursuit of their opportunity by persuading others to join them, they have no business being in business. This is not a game for hard-core gamblers.

Also absent from Stevenson’s definition is any reference to money. For the greatest entrepreneurs, money is a by-product of the achievement of a grand vision. They crave it as a way of keeping score, but if it doesn’t tally with the creation of a significant or meaningful business, it can seem hollow. It’s why you find so many serial entrepreneurs, desperate to prove they can do it again and again, and just one more time before their light flickers and dies, long after money ceased to be an issue in their lives.

Stevenson wrote that the people who turn out to be good entrepreneurs are ““as likely to be wallflowers as to be the wild man of Borneo.”” The only constant is this inclination and ability to pursue opportunity regardless of their current situation. Whatever they need, they get.

This separation of risk-taking from entrepreneurial success should be studied by more established institutions in search of an edge — London’s LIBOR-fixing banks for a start. Adding risk doesn’t make you more entrepreneurial. Managing risk in pursuit of opportunity does. People who have never been entrepreneurs, but try to take on entrepreneurial habits late in their corporate careers often make this mistake, equating massive risk-taking with heroic entrepreneurial capitalism, when the two are rarely in fact entwined. People who bet the farm are not often the ones who cultivated it from the start.

Entrepreneurial risk is also rarely just financial. It entails setting up an organization and hiring people, convincing them to leave one job to do a new one, then going out into the arena of the market and risking your reputation. It is not about one knee-trembling roll of the dice. It is about surrounding yourself with the right people, then driving execution of the myriad small steps required to achieve a vision.

Any 21st century discussion of entrepreneurs inevitably revolves back to Steve Jobs. But his two stints Apple, separated by 12 years, offered very different entrepreneurial examples. In his first stint, Jobs was very much in start-up mode, the young man in a hurry selling the world on his novel PCs while neglecting the fabric of his company.

But after returning as chief executive in 1997, he was a far superior manager, focused on building a robust and dominant organisation, a disciplined force of engineers, marketers, shop assistants and outsourced assembly workers, led tyrannically from the top. While it’s easy to admire the products Jobs introduced, his real entrepreneurial achievement was in creating the organisation capable of creating them and selling them at a level of quality and at a pace which humbled his rivals.

It may not sound sexy, but great entrepreneurs build great organisations. In a time when you can set up a company from your desktop and be selling to China in minutes, what distinguishes the amateur from the serious entrepreneur is the ability to build an organisation to take a business to scale. It is what distinguishes the brilliant solo programmer from the founders of Google.

The only problem these days, is that great organisations need fewer people than they once did. Facebook has just 3000 employees, less than one tenth the number at Google, which in turn has fewer than half the number at Microsoft. Entrepreneurs these days can create staggering wealth for their shareholders in just a few years, but they are not going to employ hundreds of thousands the way Ford or General Motors do.

Research by the Kauffman Foundation has shown that macroeconomic conditions and market cycles have had very little effect on the number of start-ups in the United States. Recession or boom, roughly the same number of companies get started. During booms, they are fuelled by the availability of credit, in recessions by the availability of talent. Rain or shine, the animal spirits remain constant.

But this does not mean governments or big businesses are off the hook. There is always more that can be done to optimise an economic environment for entrepreneurs. Immigration laws can be streamlined to allow brilliant foreign students to stay. Tax credits can be provided to help businesses in their earliest days. Big businesses can actively seek out the company of start-ups to fill their own pipelines of product and talent and keep up to speed with business innovations.

But perhaps more than anything in these straitened times, entrepreneurs need to be publicised and promoted as guardians of those animal spirits. They protect them as the Vestal Virgins once did Vesta’s fire, the hearth of Rome. Governments are so choked they can neither borrow nor afford to cut taxes. Most big businesses are condemned to ride the fates of the market cycles.

Entrepreneurs may not be the magic bullet for Western economies. But while we wait for this agonising cycle to turn, it will be up to those with the gift of making something from nothing to keep our economic spirits growling.

Philip Delves Broughton is an author and journalist. He is a Senior Consultant to Brunswick, based in New York. He was previously a Senior Adviser to the Executive Chairman of Banco Santander. His books have appeared on The New York Times and Wall Street Journal bestseller lists and been published around the world and include Ahead of the Curve and The Art of the Sale.