Summer 2012

Value for Money? Restoring the Link Between Performance and Pay

The salary of the chief executive of a large corporation, the late Canadian-American economist JK Galbraith famously said, is not so much a market award for achievement, but frequently a warm personal gesture to the individual himself.

Such views from a self-described ‘abiding liberal’ are not altogether surprising. What is striking, however, is that only a matter of years after Galbraith’s death in 2006 – a year before the current financial crisis began – the rising wave of discontent with executive compensation is no longer the preserve of left wing academics, traditional anticapitalists and professional protestors.

In Britain, Simon Walker of the Institute of Directors, that bastion of corporate standards, recently penned a paper on the ‘broken link’ between pay and performance. In discussing the so-called Shareholder Spring that has seen a number of significant heads roll, the IoD director-general cited the Association of British Insurers, Britain’s most powerful shareholder group issuing an ‘amber top’ warning over remuneration packages being proposed at Barclays. And that was before the demise of Bob Diamond, the bank’s former Chief Executive whose combination of salary, share options and other benefits in the years after the start of the credit crunch regularly amounted to more than £20m.

Bankers are not alone in having drawn the public ire. “The initial, and in some cases justified attack on bank bonuses is now infecting the public perception of big business,” Sir Roger Carr, President of the Confederation of British Industry, has said. Of course Carr, also Chairman of Centrica was forced to defend his own company’s payment of £4.4m in salary, shares and benefits last year to Sam Laidlaw, the Chief Executive. Despite flat profits and rising energy tariffs, Carr said Laidlaw ‘did a very complicated job’.

A combination of the banking crisis and the subsequent financial squeeze on the middle classes has certainly refocused attention on remuneration of top business leaders – and in a way perhaps not seen previously: the angry are often the customers and employees of many of the public companies concerned. “The debate is now starting to happen. This has got out of hand and we need to handle it,” one former Chief Executive and Chairman of a leading British company told me: “The fact is that the top is still floating away.”

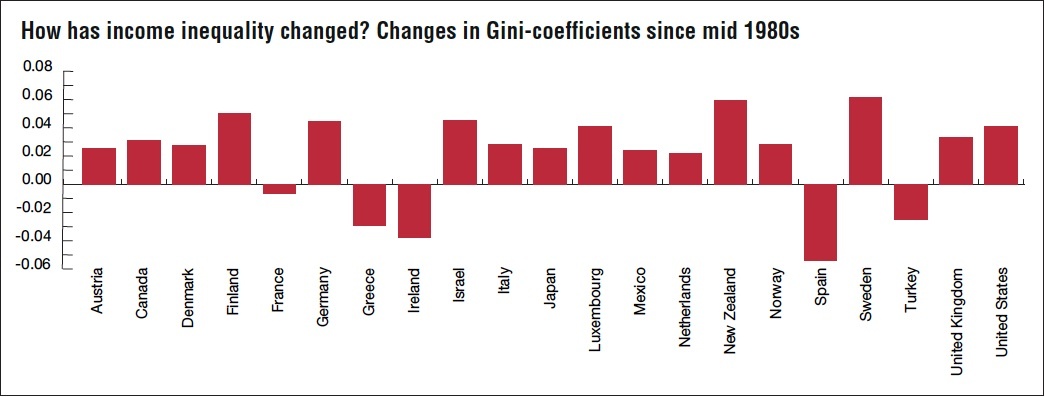

Statistics certainly support this. Academic research by the London School of Economics in 2010 showed that the share of the gross weekly wage bill going to the top decile, and particularly the top part of that decile had increased substantially over the previous 30 years – by 5.9 per cent for the top decile with the top percentile within that gaining 2.3 per cent. But such statistics failed to isolate infrequent payments, such as the year-end bonus, or cashing out on long-term incentive plans. Focusing on these measures, the gains to the top percentiles in fact have increased still further.

The top decile received £20bn more in wages in 2008, for example, due to such increases in their share – 60 per cent of that went to those in the financial sector.

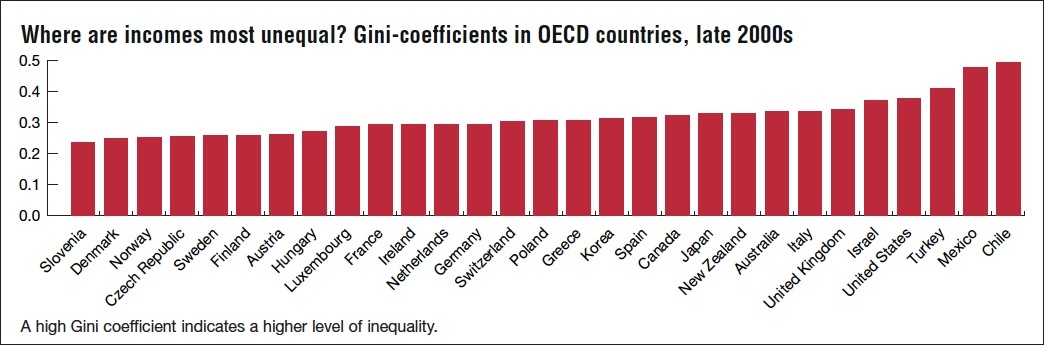

The systemic drift upwards has continued to increase. In 2010, for example, the average European CEO earned 149 times the pay of his or her employees’ average wage and, according to Income Data Services, directors of the 100 biggest listed companies in the UK enjoyed a 49 per cent increase in pay in 2011 – while average rates rose by just three per cent.

Examples of high earnings and compensation are not hard to find. Dame Marjorie Scardino of the publisher Pearson received £9m last year, as did Samir Brikho of construction company Amec, while Sir Frank Chapman of BG Group took home £9.6m. In June this year, of course, Sir Martin Sorrell of the media company WPP faced a revolt after 60 per cent of shareholders opposed his £11.6m deal, a hike of 60 per cent on the previous year. He was among a number of casualties of the Shareholder Spring that saw Andrew Moss ousted as chief executive of Aviva, and Sly Bailey departing her post as head of Trinity Mirror.

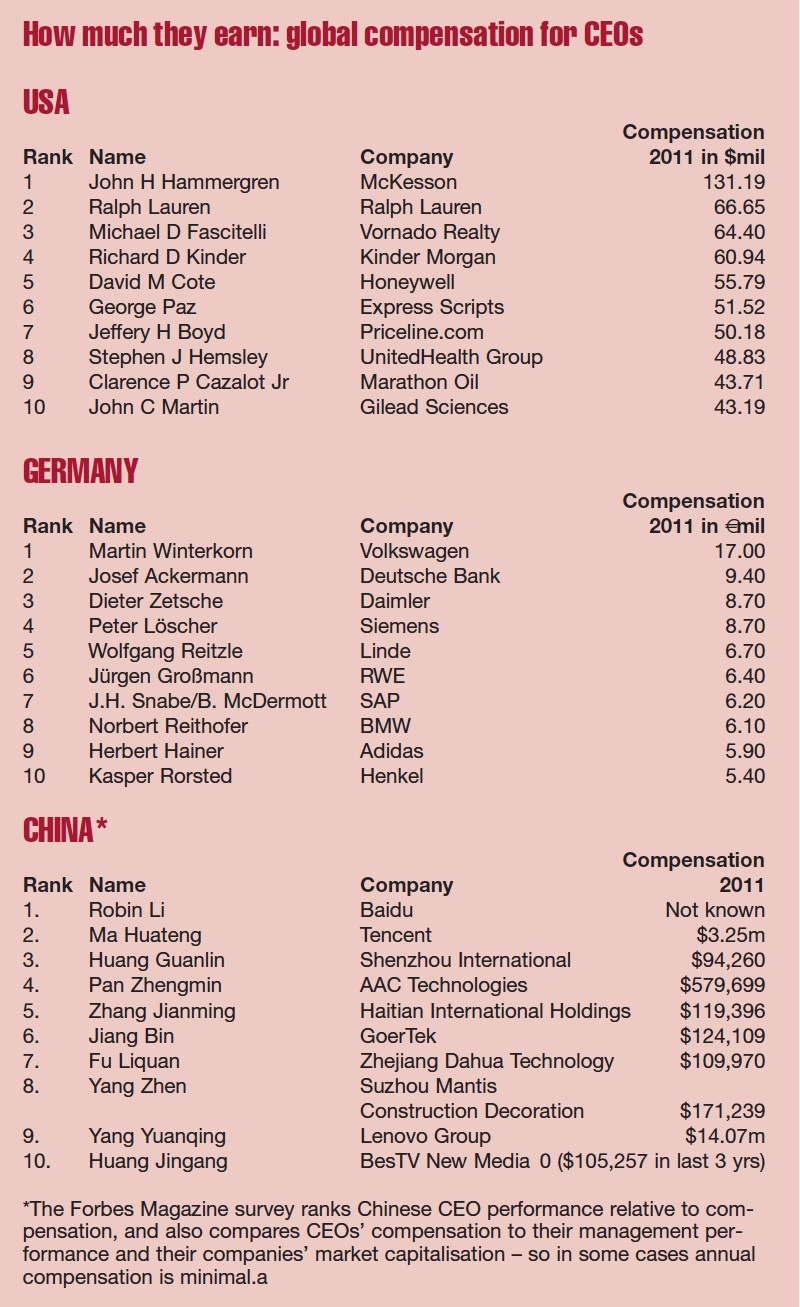

But criticism of executive pay is by no means a British prerogative. The chief executives of Germany’s 30 biggest companies saw their pay rise by almost 9 per cent last year (the British figure was 12% and an average amount of £4.8m). Martin Winterkorn, head of Europe’s largest car manufacturer Volkswagen, was the highest earner on €17m, prompting a series of declamatory headlines in German newspapers. In Belgium, news that Carlos Brito, CEO of Anheuser-Busch InBev, was to receive a bonus of more than €138m – under a long-term incentive scheme – brought protestors onto the street under banners saying the boss was ‘drunk on his bonus’.

In fact, as is well known, Europeans earn far less than their American counterparts. Research by Thomson Reuters shows that median pay for the highest earners was $2.5m in Europe in 2010, as opposed to $9.8m in the United States and Canada. The latest Forbes Magazine list of America’s highest-paid CEOs, for example, shows John Hammergren of McKesson, a California-based medical supply company receiving a total compensation package of $131.2m last year, the bulk of this from cashed-out stock options with his salary and bonus remaining flat from the previous year.

By definition, of course, while such lists provide useful fodder for the financially voyeuristic, they tend to be misleading and never comprehensive. Each depends on the year that particular data is mined, and more importantly on the nature of the remuneration metric applied by the company in question, whether salary, bonus, share entitlement or pension contribution.

At its core, the question for any leadership has always been how to measure the performance of an individual when set against the overall success – or failure – of the company more widely. In other words, how do you really judge the value of the individual to a team, and which remuneration metrics are realistic and effective in any particular case? Secondly, how should a board and remuneration committee (remcom) reward truly competitive improvement versus peer companies and individuals?

Any remuneration committee worth its salt can construct an argument to pay their chief executive (in most cases, but not always the highest paid) a very high compensation package – it is after all a competitive market place. But is that fundamentally justifiable, and can one man or woman be worth that much to the market by meeting an effectively constructed metric?

Having morphed over time, the remuneration metric is clearly an art rather than a science. In the 1990s most big companies stopped large base salaries because of the impact this would have on company pension schemes – and thus the bonus culture began. This in turn led to deferred bonus schemes, stock options, and long-term incentive plans, based on equity value.

Could stock be discounted to make it more attractive? Could the performance of the metric be re-based post facto? That the business community at large is tentatively entering the current debate suggests that no comprehensive answer has yet been found. From the perspective of the remuneration committee it is nearly always a question of horses for courses. Where individuals and companies outperform, even in a downturn, they should receive adequate compensation – in fact there is an argument to pay them more. The great mistake for any board or remuneration committee would be to find themselves trapped in a particular system at a particular time when each case is individual. High performance in a competitive market requires an appropriate metric – even when times are tough.

Disparity between performance and reward is clearly more evident when markets are depressed – and when public dissent is at its most pronounced. According to annual surveys carried out by Manifest and MM&K, between 1998 and 2010, chief executives’ remuneration more than tripled, yet any improvement in share price was all but invisible. Between 2009 and 2010, CEO remuneration in the FTSE 100 rose by 32 per cent, but the index rose just 9 per cent. Little surprise then that the public is drawing the inescapable conclusion that they are not getting value for money from certain CEOs.

If those at the top are seen to rewarded well without a corresponding level of performance, Walker of the IoD says ‘the impact on business as a whole will be severe’. He cites the UK government view that a sense of ‘reciprocity’ is crucial to business success, namely that the public must have a sense that business is a member of the society in which it operates. Without this, morale in the workforce will deteriorate, aspiration will be lost, and sooner or later politicians will be tempted or even compelled by public pressure to start pursuing ‘cackhanded intervention’.

This has already begun. The European Parliament has floated a proposal for bankers’ bonuses to be capped at 100 per cent of base salary – but this is unlikely to achieve any desired compensation reduction, as investment banks would simply increase salaries for key staff to circumvent the 1:1 ratio. In the UK, Business Secretary Vince Cable, credited with encouraging the Shareholder Spring, now seeks a ‘single figure’ that he wants companies to produce for boardroom executives to avoid confusion about the pay of senior business leaders through multi-pay plans spread over a number of years. But his intervention is already proving messy as he faces criticism from the Labour Party over signalling a reversal on annual binding votes on pay.

Meanwhile in France, President François Hollande is adopting his Robin Hood-style campaign promise to impose regulations on state-controlled companies that will prohibit top executive salaries exceeding those of lowest paid employees by a ratio of 20 to 1. Pierre Moscovici, his Finance Minister, has said the pay squeeze will come into effect over the next two years, in an effort to ‘make state companies more ethical’ and respond to ‘the demands of justice and transparency’ at a time of economic crisis.

Under this plan, Henri Proglio, CEO of the electricity company EDF, would have his annual salary slashed by 68% (from €1.55m to €505,000). Luc Oursel, president of Areva, risks having his current package plunge by 49%, while Jean- Paul Bailly, head of the French postal service, La Poste, will be in for a 41% cut.

Source: Forbes Magazine

How willing they and other senior managers will be to take such a dramatic ‘haircut’ remains moot: legal challenges seem likely to undermine the process, and targeted CEOs may refuse to lower their salaries and stay under contract until they can jump to the private sector. In fact, as most commentators note, the measure may end up being little more than symbolic.

However, some believe that intervention efforts by governments will indeed force the best managers to seek safety in the private sector, and in different jurisdictions – such as Singapore, Hong Kong, or the United States, as was the case with the imposition of higher taxation. “The private sector is going to become the safe haven for talent,” according to one consultant who advises a number of remuneration committee. “And I think there will be movement. After Bob Diamond, for example, we will see a number of Americans heading home.”

Another side effect of government intervention has been the growth of such consultants specialising in compensation. Remuneration committees are now looking for others to help shoulder responsibility. The consultants help the committees to track the market and demonstrate how competitive a company is relevant to its peer group. A problem with this model is that in order to prove the worth of any company in the market, the consultants will always tend to push up the median salary. Ultimately, few believe that is sustainable.

The way forward remains unchartered. While a fudge of some sort is the most likely solution, in the banking sector, at least, one success story merits exploration: that of Handelsbanken, the consistently high performing Swedish business which has delivered better than average returns for 39 years straight. The bank emerged from two crises, 1992 and 1998, unscathed, and is even the subject of A Blueprint for Better Banking, a complimentary tome by a McKinsey consultant – indeed Handelsbanken is the epitome of that archetype so often cited in recent months that would be led by a bowler-hatted Captain Mainwaring, the stalwart banker of the British sitcom Dad’s Army.

Jan Wallander, recruited to lead Handelsbanken in 1970, started with a single target: to deliver a higher return on equity than the average of the bank’s peers. He then decentralised the bank, believing that by empowering his staff they would outperform rivals. Wallander also put in place a unique incentive structure. No one is paid a bonus, bar the few staff in the small investment bank (and then grudgingly ‘because of the market’). Instead, they earn a ‘competitive salary’, and are given attractive benefits. Pay is the same for branch managers as at head office: the closest Handelsbanken comes to an incentive scheme is Oktogonen, the foundation Wallander set up for the staff. If the bank produced better than average returns, he argued, a third of those should go to the employees – each getting an equal share, be they chief executive or cashier.

Only businessmen themselves can determine whether the Handelsbanken model, or something similar, can be imitated among other banks, or indeed even applied to businesses, and whether this ‘back to the future’ approach is workable in the complex world of modern corporate life.

For many, wealth creation is at the very heart of the meritocracy and ethos of the capitalist system – and this manifestly dictates that senior men and women should benefit from that to a multiple worthy of their contribution. To stifle that ambition is potentially to stifle the market as a whole. It takes the indefatigable Sage of Omaha, Warren Buffett, certainly no slouch at wealth creation, to sum up the eternal dilemma that will continue to dog the boardrooms of every global company for the foreseeable future. “Pay for performance is fine,” he says. “Pay for showing up is not.”

Tom Rhodes is Chief Operating Officer of Montrose Associates and a former Washington Correspondent for The Times