Winter 2016

The Rise of the Strongman

As 2016 draws to an end, it is difficult to recall any other year since 1989, the time of German reunification, which provokes such a profound sense of discontinuity. It is thus eerily ironic that Donald Trump’s surprise victory was announced on November 9, the exact day that the Berlin Wall, the ultimate antithesis of globalisation, came down 27 years ago.

Back then I was a university student in the Soviet Union, and vividly recall the feeling of dislocation, becoming a foreigner in my own country, its political attitudes incomprehensible and its values alien. Luckily for my generation, the Soviet Union peacefully collapsed two years later, and a wave of democratic revolutions offered hope for renewal.

This year brought a strong sense of déjà vu, the same loss of identity coupled with a deep anxiety about the future. Like many liberal thinkers, I started to wonder whether the West, as a community of values and institutions, is now in danger of collapsing.

Not all post-Soviet societies realised their potential as they entered the post-Communist era. For some, such as President Vladimir Putin and millions of his followers, the collapse of the Soviet Union was the ‘biggest tragedy of the 20th century”. But for most of us, the educated internationalist middle classes, there is no doubt that all citizens in the West and in the East alike have benefitted from the past two decades of peace, democratic revival, globalisation and economic growth.

Political elites in the West have not been blind to the mounting problems of our times: the lingering legacy of the global financial crisis (and its aftermath), rising inequality, growing public anxiety about the impact of migration and the technological revolution affecting jobs (particularly low skilled manufacturing), spreading cynicism about corruption within national political establishments (post-Panama papers scandal), and a growing unease over the democratic deficit within some European institutions. These problems were seen as challenges that could be handled through reform – but not as political game changers.

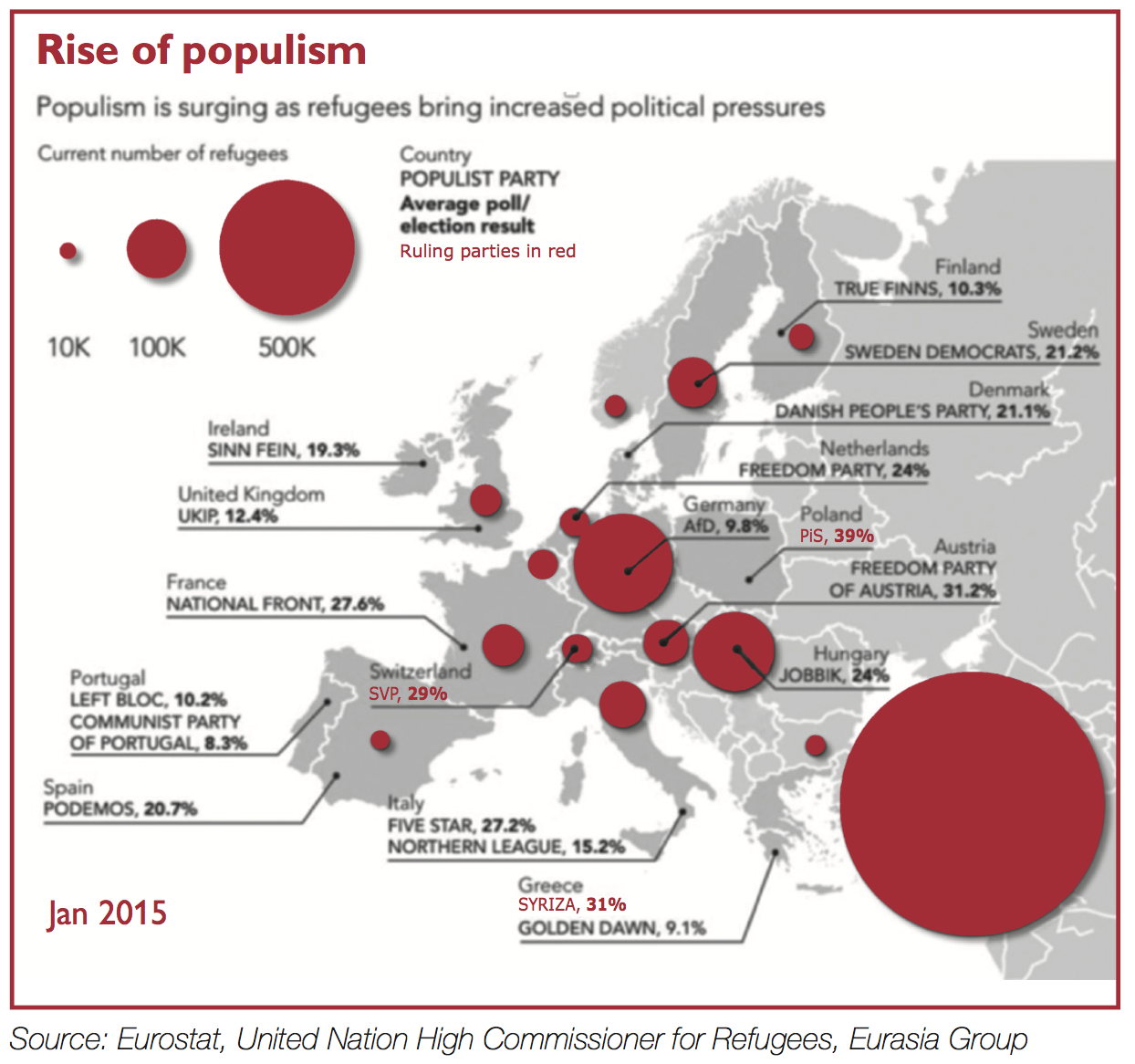

In 2016 this political complacency has been severely tested, not by the poorest nations that find themselves at the fringes of the globalisation, but by the global economic superpowers with large middle classes and the highest per capita incomes in the world. The Brexit referendum in the UK, and Donald Trump’s election in the US, have unleashed the forces of nationalism and populism on a scale not seen in the West since the1930s. Europe had seen the election of illiberal nationalist politicians well before the Trump’s rebellion. Czech President Milos Zeman who is known for his anti-Muslim views, recently called for a Czech referendum to leave the European Union. Prime Minister Viktor Orban, whose party Fidesz has twice won a constitutional majority in the Hungarian parliament, was the first to “build a wall” to stop migrants crossing into his country. Orban’s only credible opposition is Jobbik, the far-right nationalist party known for its anti-Semitic and anti-Roma stance.

Source: VLADIMIR PUTIN

In Poland, the victory of the right-wing Law and Justice Party was followed by the roll-back of democratic checks and balances, prompting the European Commission to investigate Poland’s adherence to EU’s core democratic values. Greece has produced several populist governments, alongside the rise of far-right nationalists. Earlier this year, the far-right nationalist candidate almost won the Presidential election in Austria.

Trump’s victory has turned Europe’s illiberal populists from political outcasts into the vanguard of political transformation for the democratic West as a whole. At least, this is how they themselves have chosen to interpret the Trump phenomenon. Orban declared that Trump’s victory is tantamount to the end of “liberal non-democracy” and the era of “political correctness”. For him, like many other nationalist politicians, 2016 has not been a dangerous aberration but the dawn of a new era in Western politics. Upcoming elections in the Netherlands, France, and Germany pose a danger that Trump’s political tsunami could engulf other parts of Europe. Even if the outright victory of anti-systemic parties remains unlikely, nationalist and populist forces are certain to strengthen their sway over national politics. In a number of European states including Bulgaria, Estonia and most recently Moldova, pro-EU leaders have lost recent elections to more Euro-sceptic and pro-Russian parties.Real and Present danger

If not contained, this populist revolution could undermine or even reverse many key achievements of the post-Cold war era.

Internationally, this tide of nationalism challenges the future of the European Union, the most successful example of economic integration in the world. Similarly, Trump’s “America First” approach could well undermine the credibility of NATO, and with it the principles and values underpinning the multilateral post-Cold war security order. It erodes free trade and revives protectionism, threatens to rollback efforts to stifle climate change and leaves the Western world exposed in the face of an increasingly assertive Russia and China. On a domestic level, the rise of illiberal populists invariably leads to weakening democratic checks and balances, the marginalising of institutions (including traditional political parties), weakening of the rule of law and the introduction of state dominance over the media. These regimes thrive on exploiting divisions within societies and legitimise selective application of human rights principles. In some cases, nationalist politics may even threaten the integrity of states. British leaders face a serious challenge in reassuring those in Scotland and Northern Ireland who firmly opposed Brexit that a retreat from the European Union can be in their best interests. Few challenges to the post Cold War consensus are more damaging than the erosion of Western moral and political leadership at a time when illiberal strongmen are asserting their influence along Europe’s large and increasingly unstable periphery. If not for the US tradition of strong institutions, and the regular rotation of leaders through competitive elections, President-elect Trump would belong more naturally to the company of Vladimir Putin of Russia, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan of Turkey, President Xi of China and the late Hugo Chavez of Venezuela, than to those of other Western democracies. Some democratic leaders – like President Narendra Modi of India and Prime Minister Shinzo Abe of Japan – to a lesser extent fall into a category of decisive charismatic leaders capable of commanding decisive influence at home and increasing geopolitical clout abroad.

Modern authoritarian strongmen regimes do not only build their power on tyranny and repression, although in both Russia and Turkey many independent journalists, civil society activists and political opposition leaders are harassed and jailed. Instead, they create their legitimacy and popular support by unleashing a patriotic struggle against the enemy within and without. The West, including the US in particular, is often portrayed as conspiring to weaken, humiliate and even dismember these countries, while domestic opponents are cast as mere agents representing the interests of hostile outside forces.

The Russian president, who continues to enjoy approval ratings of more than 80 per cent, has used the state-controlled media to amplify alleged US interference in Russian domestic affairs. President Erdogan has repeatedly accused the US and Europe of supporting Gulenists and Kurdish groups. For Prime Minister Orban, his freedom fight with the EU and most recently his vocal opposition to migration, helped to raise public approval ratings. In all cases, state control of a media that spreads these messages has become the key weapon for ensuring the survival of the régime. In the economic sphere, strongmen survive by enlarging the group that benefits from the government’s social and business largesse (subsidies), and in each case this involves the expansion of the middle class. In Russia, Turkey, China and even Hungary, illiberal nationalist regimes are supported by a middle class that now has a large share of members either directly representing the state or dependent on its patronage to maintain its consumption habits. In Russia only a small share of the middle class comes from the private sector, over 90% are either state employees or beneficiaries of the state sector, which now accounts for a staggering 70% of the economy. In Turkey the AK Party has overseen a remarkable expansion of the Turkish middle class beyond urban centres. This voting bloc now depends on government support for maintaining high social spending; increasing minimum wages, and suppressing interest rate rises. In Hungary much of the employment comes from public works schemes, while Fidesz supporters, among small and large business owners, are repeatedly rewarded through government policies. It is too early to say whether President Trump and some European leaders will be tempted to borrow from their authoritarian peers’ political toolbox. Trump’s campaign was based on the divisive politics of identity. Ideals of equity, equal rights, diversity and inclusion were submerged under the weight of rhetoric that raised racial and ethnic tensions and inflamed passions against imagined enemies – Mexican migrants, Chinese exporters, and Muslim refugees. Dani Rodrik, a Turkish economist at Harvard University concludes that Trump poses a very real danger in undermining norms that sustain our liberal democracies. There is a good chance that the President-elect will resort to the same tactics he adopted during the election to help sustain his popularity once in the White House — particularly if his economic plan fails to deliver results and provokes a popular backlash, compounded by new revelations of corruption and mistreatment of women. The Brexit campaign and its aftermath have also divided British society. As economic pain associated with the uncertainty of UK’s lengthy untangling from the European Union becomes real, these divisions are likely to grow even uglier. In a surprisingly populist turn, Prime Minister Theresa May has denounced a rootless “international elite” as the source of country’s economic and social problems, and vowed to make capitalism operate more fairly for workers. It would be hard to reconcile this with a vision of Britain as a champion of innovative businesses and venture capitalism. Residents of the economically deprived regions are in fact set to be the most negatively affected by the loss of EU funding and by the almost inevitable rise in university tuition fees. Ironically, these were the very people with strong anti-establishment views who overwhelmingly voted to leave the EU.

Source: Eurostat, United Nation High Commissioner for Refugees, Eurasia Group

In the US, much of Trump’s legacy will depend on the new Administration’s ability to increase economic well-being for the American middle and working classes. Trump has promised to initiate large infrastructure projects and to protect US jobs by denouncing free trade regimes and to resort to protectionism to revive a declining US manufacturing base. Having raised expectations among the residents of America’s Rust Belt states, however, he has little change with which to meet them: Trump’s policies are unlikely to bring about a strong economic revival in these communities. On the contrary, they are likely to pay a price for some of his policies, not least in the form of much-expanded national debt and increased inequality.

When the full scale of his economic disappointment becomes clear, Trump can resort to strategies characteristic of strongman regimes. To distract attention from failures at home he can seek refuge in identity politics or in foreign policy gambles. But these could rip American society apart along racial and ethnic lines and destroy the very foundation of the transatlantic community, which the US helped to build after WWII.New world order?

This growing appeal for illiberal democracies and strongmen carries significant risk for the future of global security. America’s ‘unipolar moment’, a term coined by Charles Krauthammer in his famous 1990s Foreign Affairs essay, has recently given way to a version of de Gaulle’s multi-polar world, strongly embraced by the rising non-Western powers, particularly Russia and China.

The dawn of the new world order was precipitated by the US retrenchment from global leadership in the wake of Iraq war and global financial crisis. This trend appeared in the final years of the Bush Administration, as the US struggled to contain conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan amid an escalating financial crisis. It continued under President Obama. The outgoing US Administration has withdrawn from many foreign commitments thus leaving space for new, self-proclaimed “great powers” to assert influence in many parts of the world – from Eastern Europe to Central Asia, Africa and parts of the Middle East.

In the short to medium term, Brexit and Trump’s Presidency are likely to mean that the transatlantic community will be preoccupied with internal challenges, including a redefinition of its approach to burden sharing. With NATO and the EU recalibrating their approach to collective security, their ability to undertake complex and costly force projection operations will be limited. The emphasis will remain on building resilience and reassuring NATO’s Eastern European members, potentially in the context of a diminished US commitment to European security.

Western retrenchment would encourage a more assertive and activist foreign policy on the part of other rising powers, keen to help shape the rules of the game governing this new post-post-Cold war multi-polar world order. For strongmen regimes like Russia and China, these rules are clear: they combine the concept of hyper-sovereignty (built on the principle of non-interference in domestic affairs) with great power relations built around realpolitik, including the recognition of spheres of influence and rejection of permanent alliances in favour of ad hoc coalitions. This set of principles sits on the opposite side of the spectrum from the collective security system that existed before and after the fall of the Berlin Wall. In the past three years, the key standards that underpin this collective security system have been severely undermined: first by the Russian annexation of Crimea and later by the collective failure of international institutions to stop Syria’s bloody civil war, that has already claimed half a million lives. The grave danger now is that a President Trump will find the offer of a new ‘multi-polarity’ attractive to the kind of limited foreign policy objectives that he championed during the election campaign. While it is highly unlikely that the US and Russia will form strong co-operation in terms of foreign policy, it is almost certain that at least in the short term, President Trump will seek to negotiate a truce with Putin that could be detrimental to the interests of many US allies both in Europe and the Middle East. If Trump and Putin fail to find a stable modus vivendi, their political courtship could soon turn into a serious crisis. Two unpredictable men governing nuclear superpowers with hyper centralised decision-making systems could swiftly escalate their personal rivalry to the point of a Cuban missile-style crisis. Similarly, the US and China now find themselves at the highest risk of confrontation since the two fought a proxy war in Vietnam. Trump’s declared intentions to scale back America’s security commitments in the Asia Pacific region could prompt Beijing to take a more aggressive stance on both the South China Sea and on Taiwan. Europe’s challengeIn this increasingly unstable world, Europe is less able to project its soft and hard power. As a slow-moving multilateral institution, which requires consensus among all member states, the EU cannot compete with strongmen whose strengths lie in unpredictability and the absence of constraints, either institutional or normative. Its ability to showcase the strength of institutions as opposed to personalised power is hampered by Brexit. Europe’s economic prospects do not look promising either: while the Union has weathered the impact of the global financial crisis well, it now faces a prolonged period of low economic growth that is likely to put further pressure on its middle classes.

The rise of populist political forces threatens to undermine Europe’s appeal among aspiring democracies in its neighbourhood and beyond. The absence of a political consensus of future enlargement could make further convergence between the EU and its neighbours, including Turkey, Ukraine, some Balkan states and in the future the UK, more problematic.

In the meantime, Europe is increasingly viewed by some of its more assertive neighbours, like Russia, as an object of influence rather than a partner for economic and political dialogue. Russia is already building close ties with some of the nationalist parties both in Central and Eastern Europe and in the “old Europe”, like Marine le Pen’s Front National.

In this context, the coming year is of vital importance to the EU. The Trump effect may have inspired some anti-establishment groups to vote for their candidates, but polls – if they are to be believed in the “post-truth world” – also show that for many Europeans, Brexit and Trump’s victory have created a strong urge to protect this unique project of integration that has helped to maintain peace and build prosperity for more than 50 years. This calls for a new generation of responsible European politicians with a strong determination to modernise and democratise the EU. The alternative is too horrific to contemplate, particularly for those of us that belong to the post-Communist generation.

The rise of populist political forces threatens to undermine Europe’s appeal among aspiring democracies in its neighbourhood and beyond. The absence of a political consensus of future enlargement could make further convergence between the EU and its neighbours, including Turkey, Ukraine, some Balkan states and in the future the UK, more problematic.

In the meantime, Europe is increasingly viewed by some of its more assertive neighbours, like Russia, as an object of influence rather than a partner for economic and political dialogue. Russia is already building close ties with some of the nationalist parties both in Central and Eastern Europe and in the “old Europe”, like Marine le Pen’s Front National.

In this context, the coming year is of vital importance to the EU. The Trump effect may have inspired some anti-establishment groups to vote for their candidates, but polls – if they are to be believed in the “post-truth world” – also show that for many Europeans, Brexit and Trump’s victory have created a strong urge to protect this unique project of integration that has helped to maintain peace and build prosperity for more than 50 years. This calls for a new generation of responsible European politicians with a strong determination to modernise and democratise the EU. The alternative is too horrific to contemplate, particularly for those of us that belong to the post-Communist generation.

Oksana Antonenko is a political analyst. Previously a Senior Fellow at the International Institute for Strategic Studies, she is currently writing a book on The Rise of Strongmen Regimes: a Challenge to the Global Order.